- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

What is the comparative of prolific? John Kinsella, in this latest extension of his ‘counter-pastoral’ project, manages a tricky balancing act between the extreme givens of the bush and the fashions of art gallery and English Department. A belligerent posturing is implicit in Kinsella’s term, while there is only so far a poet can be anti-Georgics or extra-Georgics or post-Georgics before the game becomes exhausted or obvious. Nevertheless, ‘counter-pastoral’ is an extended essay that takes the pastoral concerns and illusoriness of ancient and eighteenth-century Europe and tests them against our own realities: environmental degradation, both random and systematic destruction of nature by humans, and a seeming indifference on the part of many Australians to doing anything about them.

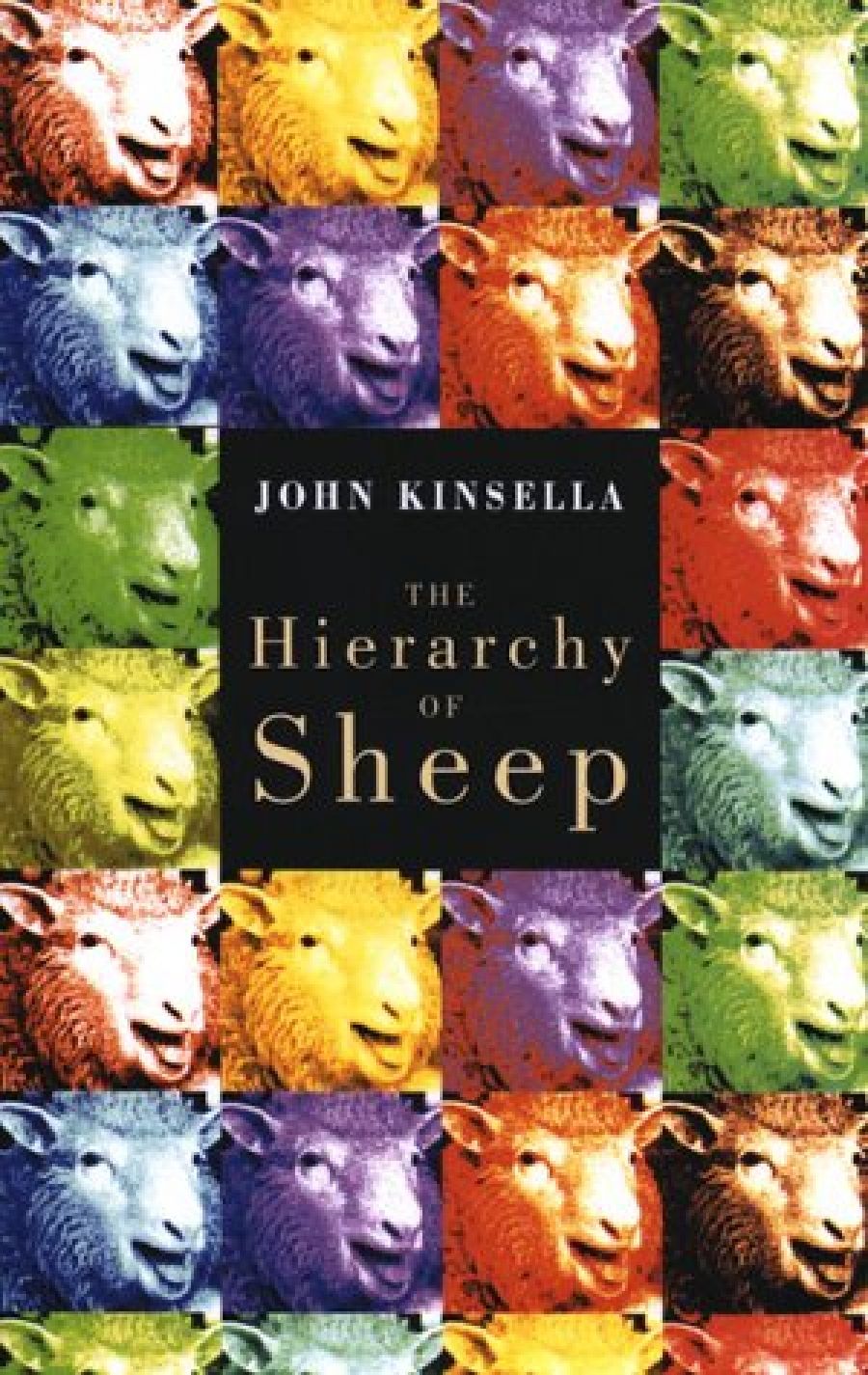

- Book 1 Title: The Hierarchy of Sheep

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP, $18.95 pb, 85 pp,

A lead to this condition of anxiety within nature is presented in the opening poem, ‘Adaptation’:

The chemical body

shielded by foliage

plays havoc with the seasonal

turnaround, the adaptational

quirks of vampire finches

on a small island of the Galapagos

archipelago.

Charles Darwin’s inheritance informs the syntactic shifts, permeates the general contents and dominates the meaning. Pastoral is asking for it, and Kinsella has merciless fun borrowing its antique gambits for his own purposes. Gambling with gambolling, one might say. Indeed, it could be said, what else would you expect! Kinsella cuts clear beyond irony in his use of pastoral antecedents which are phony or unsatisfactory models. His phrase ‘the grim idyll of the interior’ is an adequate indicator of this poetry’s preoccupations; it also exposes a dilemma at the heart of Kinsella’s work. After all, an idyll that is grim is still an idyll. The most intensely descriptive and relentless passages usually deal with violence in nature and human ingenuity at stuffing things up. This poet’s absorption with grimness can be read as a late-romantic fascination rather than genuine disturbance or horror. Consider the poem title ‘Cut in Half by a Sheet of Corrugated Iron Ripped from a Shed by a Strong Wind’, with its offhand final remark, ‘didn’t know what hit him’.

Intended or not, the result is a rich evocation of death within nature, with no escape. The drive of the language, its sense of inevitability, can be seriously at odds with the political moral that is the unwritten centre of the poem. One is reminded of Philip Hodgins’s dire dictum that all poetry is about death. Determined field notes on the actions of nature (‘where THE LAND does its urge thing’) use a language that talks over the top of itself, frantic to include the full catastrophe. Nature is the reality that is more prolific. Just as the poems burst forth with recognisable natural achievements, so also, they contain the signs of their own transience and decay. Over and over, Kinsella displays these changes. Intrinsic to the poems’ success is the acknowledgment of what any ‘success’ in nature inevitably implies; it is quickly observable how often words like ‘falling’ and ‘failing’ show up in the rear-guard actions of his poetry.

Before such reality, the cultural world of cities looks uncertain and insubstantial. The future is very uncertain when it’s a grim idyll. Inside dangerous nature we come face to face with humans. Kinsella’s world is populated with wife-beaters, drug crazed country hoons, corrupt politicians, business sharks, hardened farmers, mindless hedonists, bigots, and low life. Sometimes they are portrayed satirically to the point of uncomfortable farce (e.g. ‘Killing the World’), other times with a keen eye to their cruelty, shallowness or, just occasionally, achieved self-awareness. In such company it is a relief to meet Mikhail Bakhtin, Kevin Hart or some other conveyor of civilisation, their names prefacing the poems or laced through the lines via the preferred Kinsella strategy of exposing his sources in the art itself. Who Kinsella feels more comfortable amongst remains an open question.

So where do we locate the salve to this callousness of conditions and events? We are led to the conclusion that heartlessness and random destruction might well be the main themes means and ends to the situations he depicts. Clues elsewhere in the work to possible solutions, visions or even just escapes from this inevitability are not so readily identifiable. Nearly every poem has what was referred to earlier as one kind or other of political moral as its unstated centre of gravity. Poetic alliances between the aesthetic and the political can leave the reader with divided allegiances. The superb presentation of, say, collapsed land or some unlikeable hothead is a valuable asset, while the futility the poems engender before such facts leaves one exasperated. A powerful evocation of crisis is nevertheless achieved, the possibility of positive change left hanging. ‘… Progress a lie, we are / encircled and never / get free however the day / strains and fails …’ (‘Parallels’). The extent to of our tolerance and awareness, social questions that reach down into our own personal well-being – what can be described broadly as liveability – are the wellspring that saves Kinsella’s work from indulgence, indifference or some form of ethical despair. The same value of liveability gives meaningful purpose to an existence and a world that would otherwise be little more than unavoidable torture.

That said, there is much to enjoy in Kinsella’s varied display. A subversive humour is evident from the outset in the title of the book, for what creatures are less hierarchical than those woolly heads that follow one another into the wrong corner of the paddock? It’s the humans who invent the jokes; Dolly the clone is close by in Kinsella’s ovine sequence. We also later learn that it is tame lambs that are lowest in the hierarchy, being the first to get killed. Kinsella shares Hodgins’s laconic bush wit in the two-line poem ‘Rainwater Tank’ –’Half full in winter/Half empty in summer’ – raising the question, why laconicism, that specialty of Australian speech, has not been cultivated more as a form. There’s a lot of it around. Mind you, once cultivated, is it still laconicism?

Kinsella’s clear talent for borrowing voices is most explicit in his loving mimicry of John Forbes’s delivery in poems dedicated to that poet:

The interior fights back

like the inoculated rabbit

in the Flinders Ranges

as you watch an adult movie

just to find that it doesn’t

do the trick, despite a view

from the hotel window

out over the sweeping coast,

and summer fashions

in the bar that might be

pure Sydney.

In fact, Kinsella’s sheer diversity of voices and prosodic skills are a treat. There is no let-up. Here, as elsewhere, we can enjoy for its own sake a masterful use of the colloquial, as in his short play written entirely in hilariously convincing rhyming couplets: ‘Well, I’d like to get some shooting in / I’ve had enough of this fucking wheat bin.’ Kinsella’s exuberant interplay of scientific and artworld language, literary reference and jargon keeps us ever on the alert, and even more so his sudden compression of a philosophy or a state of being into a few words as, for example, where he ends the unsettling coverage of a Perth sunset with the line: ‘Darkness intensifies, forcing biographies.’

Comments powered by CComment