- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Australian Mahagonny

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Given its present rise in popularity, if you haven’t been to Broome recently, you’re obviously hanging out with the wrong crowd. Even the Queen – always so prescient – visited Broome in 1963. Broome has suddenly undergone another rebirth: as a tourist destination, historical and cultural centre, and as the home of Magabala Books. While Sydney has Williamson and White, Broome has given us the immortal musicals Bran Nue Day and Corrugation Road.

- Book 1 Title: Broometime

- Book 1 Biblio: Sceptre, $29.95, 294 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

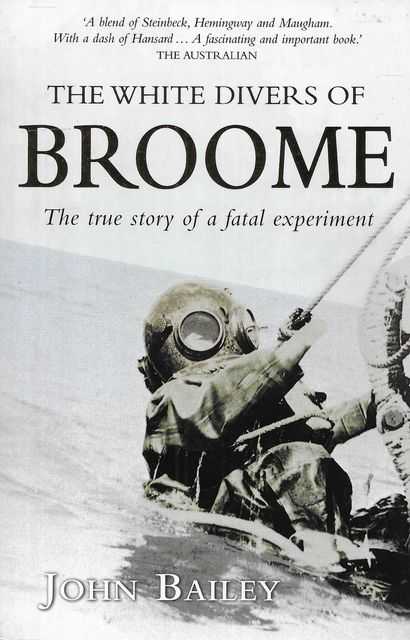

- Book 2 Title: The White Divers of Broome

- Book 2 Subtitle: The True Story of a Fatal Experiment

- Book 2 Biblio: Pan Macmillan $30 pb, 301 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

These two books work as bookends: Bailey’s an historical saga, Coombs and Varga’s a modem observation. It is difficult not to interweave the two together. Broometime has the added intrigue of being a collaboration by two writers, both eastern Australians. They make no bones about searching for a country town to write about and end up in Broome. They find it is the town they have been looking for. Initially, the locals are surprised that they have come to the town not to record the past but to find the present.

Broometime starts with them as obvious outsiders; moving into a drack of a place which they name Rat Palazzo. Obviously, they won’t last, fighting within their relationship every day, every hour. Susan says, ‘Yet I’m strangely confident. God knows why ...’ Confused thoughts flit through their narrative until they leave for their cool home in the Southern Highlands of NSW. Broometime ends on a note of poignant nostalgia, leaving the reader with similar emotions. Lovely writing, being accepted, and at the same time knowing they will have to go, and come back, and go again.

Broome, with a population of about 9,000 people, is isolated on the north-west coast. But it is not a hermetically sealed society. It is stubborn, droll, self-deprecating, proud, tired, heavy-drinking, sometimes violent, wet-hot during the monsoon and dryhot at other times; the two seasons move inexorably by turns, as do the locals.

In another age, the locals would be described as misfits. The relaxed Catholic Bishop Chris (his name doesn’t matter he’s just known as the bishop) is called to Rome and returns chastised by ecclesiastical propriety, which you know won’t last. An endless diplomacy between Aborigines and white intruders, blacks and part-blacks, Malays, Koepangers (West Timorese), Chinese, and Japanese. Uncle Kiddo says, ‘My dad was from Trinidad, my mother was a half-caste Chinese-Aboriginal … I don't know what to call myself, so if anyone asks me I say, “I’m just an old Australian Abo!”’ Identities flow in an endless progression.

However, none of them is confusing. ‘Is it possible to be as Kevin Fong tries to be – Chinese one day, indigenous the next, Malay the next? ... And he married white.’ ‘Ferals’ and ‘mung beans’ are the local words.

Two of the most beautifully drawn characters are Gordon Bauman and his young, ‘quick-witted’ Aboriginal lover Damien Kerr. Gordy is middle-aged, a flamboyant cross-dresser and a capable Aboriginal Legal Service barrister. Their relationship is turbulent, to say the least, and, on Gordy’s side, somewhat sexually confused. Yet there is a real affection and caring between them. Living on the edge? Not always: their friendship is accepted locally, if not discussed. It is clear that Coombs does not get on with Gordy as well as Varga does. Such is the sincerity of their writing that they are often quite incisive about themselves. The highlight for me was the description of cyclone Thelma. As the cyclone approaches (the local hospital orders 1100 body bags), people evacuate or brace themselves for a devastation that never happens much like in Brecht’s Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny.

The authors are perceptive, analytical, honest about their multitude of characters and events. Everything is normal but somehow never ‘normal’. And after a while, you forget that the book has two authors. Have nine months in Broome subtly altered their individual identities? The great thing about this book is that it is abundantly generous.

Bailey’s book is more academic, though more harrowing. He traces the history of the pearling industry from its sordid beginnings. Mother-of-pearl shells were traded from Broome to all the capitals of the capitalist world to produce ‘decorations on fine furniture and walking sticks, as ashtrays in gentlemen’s clubs, on ladies’ spectacles and on the handles of dandies’ revolvers’ - but above all to make buttons. So much misery for the sake of decorations for the rich. First the Aboriginal tribes are dispossessed, then brutally exploited. Aboriginal women – herded, raped, pregnant, shot – are forced to dive deeper and deeper once the pearl shells on the beach and shallow water have been gathered. They are replaced by more willing and seemingly more complacent Asiatics who can dive to greater depths and for longer periods – the theory advanced by the white owners of the luggers. Twenty per cent of divers died every year, a shocking statistic, but profit was valued above life.

Enter the Federal Government. By 1912, the White Australia Policy was now law and boom-town Broome was subjected to ‘Whitewashing’. In forty or so years, Broome had almost become a Japanese enclave. This was ideologically intolerable. ‘Let the Japs, the Malays and the Koepangers be warned,’ the politicians fumed as they imported twelve Englishmen from the British Royal Navy to prove that white was better. It wasn't to be. The bends got most of them, as it did the Aborigines and Asiatics. This is Bailey's reconstruction of the death of one of the English divers:

He looked up and saw that the sun had turned a bluish-black, like the colour of a bruise. The pain was no longer with him. Then in the strangest of sensations, he felt areas of his brain close down, one after another.

The fruit of ignominy survives, suggesting that the main issue is not a republic, nor democracy, but multicultural Australia.

Comments powered by CComment