- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Lonely Cage

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Despite attempts, revived in recent weeks, to discredit the term ‘stolen generations’, what cannot be denied in the semantics of that debate are the excruciatingly painful experiences of the children involved. While the meanings of such terms as ‘removed’ and ‘abandoned’ are complicated in a racist culture by indigenous peoples’ disenfranchisement, poverty and illiteracy, the devastating nature of separation from family in childhood must never be overlooked or underestimated.

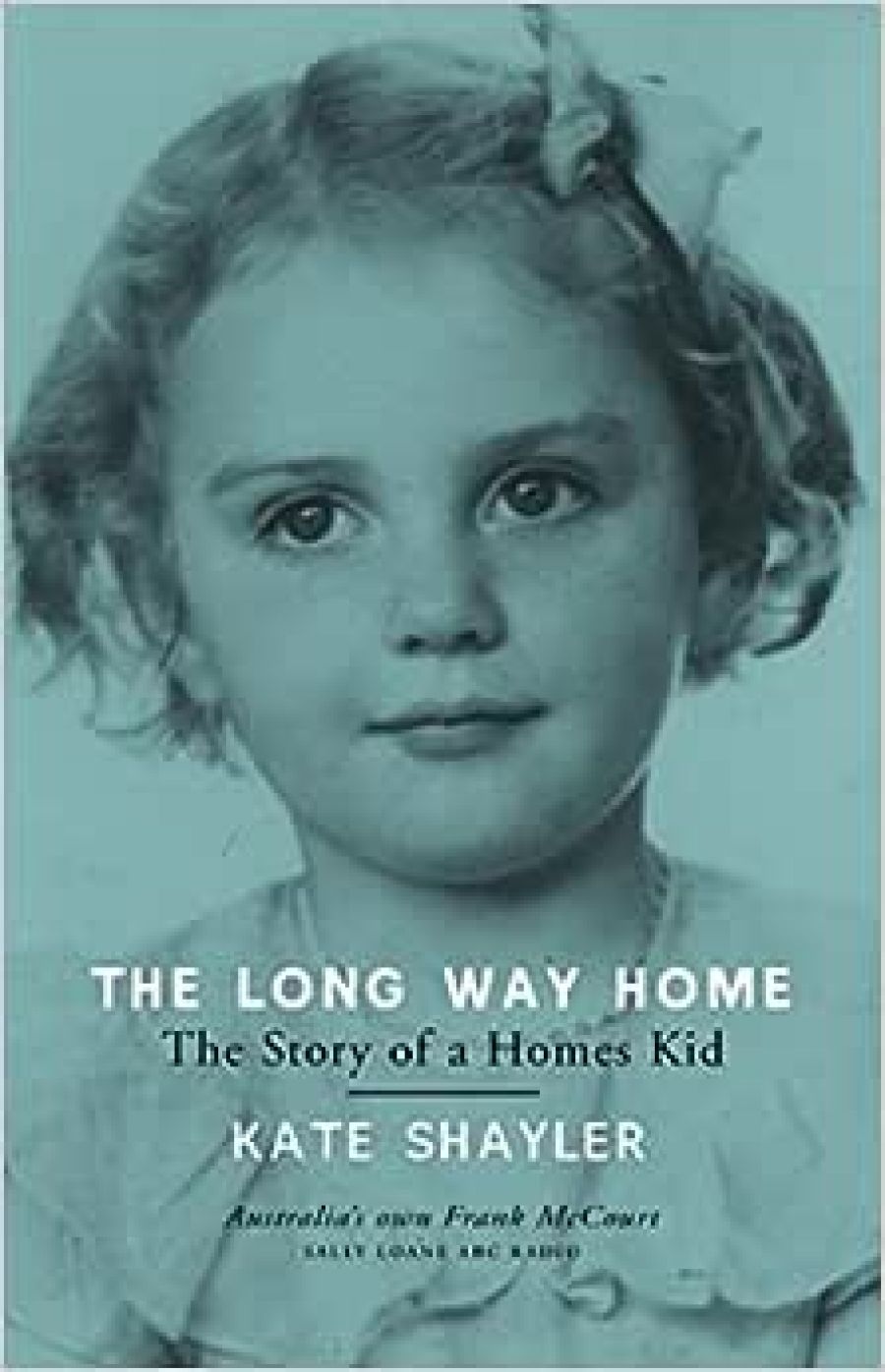

- Book 1 Title: The Long Way Home

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Story of a Homes Kid

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House $19.95, 346pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The Long Way Home is Shayler’s autobiographical account of her twelve years in a children’s home. The journey begins with her mother’s death when Kate is four, which results in her and her two siblings being placed by their father in the Burnside Presbyterian Homes for Children. There, estranged in various ways from her brother and sister, Kate experiences disorientation, isolation, and psychological and physical abuse, but gradually learns to abide by the rules, conform to the regimented lifestyle, and to make the best of things. Her moving life-story is littered with poignant comments that hint at the fundamental poverty of the children’s lives: at Burnside ‘being good meant not needing attention’; on visiting days her father’s laugh ‘was the only adult laugh we heard now’; she loves bath time because ‘it feels a tiny bit like Mummy is near when the big girls play with me and show me kindness’.

To compound Kate’s misery, her father begins sexually abusing her on ‘outing days’. This betrayal by the one person she trusts and loves deeply is devastating. Kate has to create two fathers for herself, doing everything to avoid being left alone with the ‘dark’ version. When her precocious knowledge of sexual matters is revealed at Burnside, Kate is punished and stigmatised as ‘dirty’, rather than the origins of this knowledge being investigated. Despite these heart-breaking circumstances, Kate’s narrative has moments of humour revealing her resilient spirit and the camaraderie that developed among homes kids at school to protect them against ‘outsiders’.

After twelve years of institutional life, Kate’s dream of returning home is achieved. Paradoxically, this event is as traumatic for her as her initial arrival at Burnside. Living with her elderly father and her brother, she is expected both to keep house for them and to hold down her first job.

After years of neglect, the family home is filthy, swarming with cockroaches, and, for one who is used to communal living, very lonely. Yet again, Kate is subjected to her father’s sexual advances, so that she is constantly on guard and her home becomes a ‘lonely cage’. Having craved a ‘real home’ all her life, Kate realises Burnside may have been the closest she is able to get to that ideal and that it had, at least, provided her with a surrogate family.

The Long Way Home is an affecting record of one girl’s experiences in a children’s home and hints at their long-term consequences. It is written in the first person, from a child’s perspective, in a stream-of-consciousness present tense. Short, truncated sentences express Kate’s childhood thoughts, while interior monologues accompany much of the spoken dialogue. If the immediacy of this language successfully conveys a child’s feelings of abandonment, distress and limited understanding of many events, it has drawbacks. Denying herself the illumination of hindsight, Shayler alludes to various issues that the child Kate did not fully grasp, but that must be transparent to the adult Kate and that the reader would like more information about, such as the existence of an extended family that her father denies or conceals. The privileged double perspective of the autobiographer is a valuable narrative tool that Shayler omits to wield.

To warrant publication, autobiographies must be one or more of the following: written by someone famous, particularly well-written or capturing an interesting, tragic or unusual life. Shayler’s account fulfils the final category and documents a little-known period in Australian welfare history. However, narrating her autobiography was clearly also a cathartic experience for Shayler, which unfortunately, at times, renders her writing self-indulgent.

The Long Way Home is the account of a ‘stolen childhood’, purloined by circumstance, by the rigid and inappropriate methods of children’s homes forty years ago, and by an abusive father. It is autobiography as social history, testimony and personal therapy.

Comments powered by CComment