- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lords of Misrule

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This amusing doggerel, furnishing the epigraph to ‘On Queer Street’, the eighth chapter of this book, neatly sums up the status that Oxford Street currently enjoys as an emblem of, and shorthand reference to, the large and vibrant Sydney gay world. Its campy note evokes an older gay world of queens and drag (what in fact the US slang term gay originally meant in the 1920s and 1930s), which was how gay Oxford Street began in the late 1960s. That all receded but did not vanish with the advent of macho fashions and behaviours, clonery, leather, and Muscle Maries in the 1980s, which marked the second wave of US influence following the willing embrace of gay liberation in 1970 and after. Oxford Street is now known to the world as the site of the Mardi Gras parade, far and away the largest street celebration in Australia and probably the largest gay and lesbian street celebration in the world.

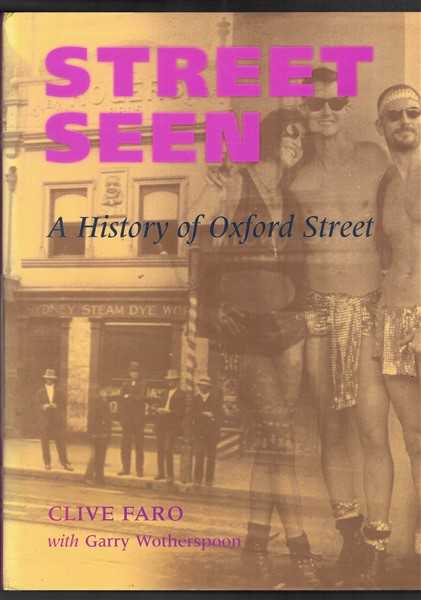

- Book 1 Title: Street Seen

- Book 1 Subtitle: A History of Oxford Street

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $54.95 hb, $43.95 pb, 324 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

One of the purposes of this engaging study in the urban history and geography of Sydney is to map out these developments. Its interests and parameters are, however, much broader and longer, and by no means limited to the gay side of things. So we follow road-building, land subdivision and town planning, developments in retailing, transport and local government, the financing of public infrastructure, and urban renewal and so-called gentrification, all of which impinge on the history of this street. All of it is abundantly illustrated, too, in this Iarge-format, handsomely produced volume.

Fire at Buckingham’s the former department store, in 1968

Oxford Street only came into existence as a renaming (commercially driven) of a section of one of Sydney’s oldest roads: the South Head Road that Governor Macquarie constructed in 1811 to provide a permanent land connection with the South Head Signal Station established in 1790 to alert the colony to the arrival of ships. The importance of the road is indicated by the facts that it was paid for by public subscription and built by the 73rd Regiment (not convicts). It did not lead to the immediate subdivision and development of land along its way. (Paddington grew after the opening of Victoria Barracks in 1848; North Bondi, Rose Bay and Vaucluse were established only after World War I.) Rather, it became a fashionable road for country rides or drives in one’s coach. The exhibitionistic strutting in today’s minimalist finery during Mardi Gras is a revival of customary uses of the road in its early days.

In 1875, the newly named Oxford Street extended only as far as Taylor Square. It was a major retailing strip, a high street in the useful English term that the book deploys. It would soon have the then latest retailing phenomenon, the department store. Faro and Wotherspoon detail the long campaign, fuelled by the City Beautiful movement, with its ideas of slum clearance, boulevards and vistas, to widen Oxford Street, which the city council finally carried out between 1910 and 1914, one of the few recommendations of the 1908 Royal Commission on City Improvement to be implemented. They point to the fact that the shop assistants who staffed these high-street shops were commonly viewed as effeminate, and quote a piece in 1895 condemning the ‘Oscar Wildes’ of Sydney who paraded and cruised on streets like Oxford Street. They seem unaware that effeminates, dandies and homosexuals were constantly satirised in the 1890s and 1900s, which is proof of their presence and even ubiquity. In 1893, before the Oscar Wilde scandal, Whaks Li Kell, in his book Cornstalk, has a lisping conversation about ‘wings’ among a group of what he called , using current slang, ‘Gussies’, and in 1903 the Truth even used the then unknown medical word homosexual in another of its harpings on the theme. Later in the year it denounced, with characteristic alliteration, the ‘preaching of paederasty’ by ‘Oscar Wildeists’. Our authors note the existence of Charles Wizgell’s Turkish Baths in Oxford Street and quote a homosexual in one of Havelock Eilis’s case-histories (Sexual Inversion, 1915) as saying his erect penis was grasped by a fellow bather in Sydney who wanted sexual activity. Faro and Wotherspoon mention the coming of cinemas but are unaware of the 1920s evidence, from court cases, of men getting off together in the convenient darkness of the new picture-theatres. The homosexual presence on Oxford Street dates back more than a century.

Oxford Street has long served as a route for civil ceremonial parades. Faro and Wotherspoon show that the Mardi Gras is the latest instance of a long Australian fascination with grand parades, which they usefully explore. Each chapter of the book is followed by a recreation of one of these many parades, including the tumultuous marching of prisoners up Oxford Street to the new Darlinghurst jail in 1841 and the grand parade to Centennial Park that was part of the ceremonies inaugurating Federation on 1 January 1901. This was reenacted on 1 January this year to mark the Centenary of Federation. The main comment after the 2001 version was how much better gays are at organising a parade.

Perhaps predictably, given intellectual fashion, Faro and Wotherspoon seek to attach to the Sydney Mardi Gras notions of the carnivalesque. It will not work as history. It is of course true that the two most famous Mardi Gras, those of Rio de Janeiro and New Orleans, are directly carnivals, the pre-Lenten festivities that in Western European, Roman Catholic countries culminate on Shrove Tuesday, French Mardi Gras (‘Fat Tuesday’), the day before Ash Wednesday and the start of Lent. While Sydney gays borrowed the name from these festivals, Australia, whether Protestant or Hiberno-Roman Catholic (i.e., morbidly anti-erotic owing to Jansenism), has no traditions of carnival. The Sydney Mardi Gras is a grafting of homosexual traditions of campery, sending-up drag and the drag ball onto the native zeal for parades. Living in often-dangerous marginality in hypocritically intolerant societies, gays have created their own Lords of Misrule. Of course, street revelry and carousing and public eroticism will have some commonalities, wherever and however they occur.

Comments powered by CComment