- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Flight of the Missionaries

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

After a three-month journey to Madagascar by steam-ship, the first thing to greet the newly married missionaries Thomas and Elizabeth Rowlands were fields of wet sugar cane. Brightly painted wooden cottages surrounded the harbour; former slaves and Arab, Indian, and Chinese traders filled the streets. ‘Rain fell heavily, but covers of rofia cloth, which swelled and thickened in the wet kept the travellers dry.’ Their granddaughter, Joan Rowlands, describes their inland journey in Voluntary Exiles. Crossing crocodile-infested rivers, bearers held the Rowlands aloft, ‘shouting and beating [the waters] with branches and poles to ward off attack’.

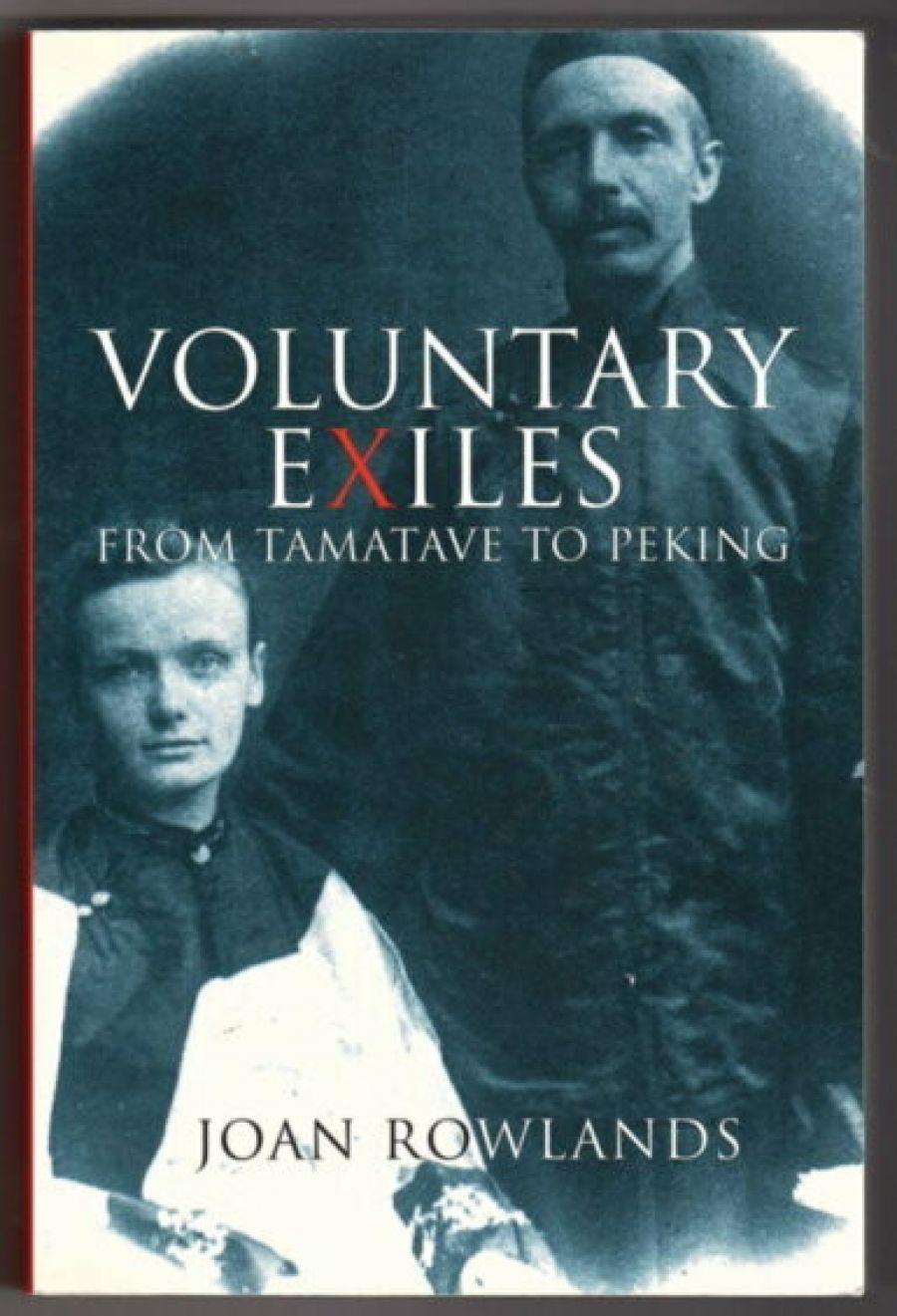

- Book 1 Title: Voluntary Exiles

- Book 1 Subtitle: From Tamatave to Peking

- Book 1 Biblio: Hale & Iremonger, $34.95 pb, 367 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Despite the years of deprivation, separation from their children, extreme rivalry between the various missionary groups, and constant risk of life-threatening diseases, the Rowlands remained in Madagascar for approximately fifty years. They both died there. When Thomas Rowlands died in 1921, a head teacher at a local theological college wrote: ‘He gave his life for the Malagasy.’ He died among the people he loved: ‘Malagasy hands dosed his eyes at last.’

Drawing on two generations of her family, Joan Rowlands intimately describes the missionary experience. Her grandparents were missionaries in Madagascar, while her parents, aunts and uncles worked as missionaries in China. Joan Rowlands herself was born in China. When she returned as an adult, ‘nothing was familiar’. The mission set up by her parents had been demolished. Nothing remained. ‘It would be another eight years,’ she writes, ‘before I met those who remembered.’

Rowlands’s book, while a family memoir and history, is also a quest It is a record of the journey made by the author in search of her own past. This is an essential part of its interest. In the opening Madagascar section, an over-dependence on primary sources slows the pace. But as soon as Rowlands returns to China, the narrative gains momentum. Rowlands obviously feels much more comfortable with the Chinese material. It is, after all, her story too. The paragraphs are shorter, the expression more confident. She introduces humorous details and vivid description that allow the story to come to life. Dressed in local clothes, with a pigtail on his back, Rowlands’s maternal grandfather, James Cormack, tried to buy a chicken in a Chinese shop. Cormack couldn't remember the word, so he asked for a chi tan ti fanu (the father and mother of an egg). The Chinese shopkeeper laughed, but understood.

Rowlands poetically evokes the home where her grandparents James and Annie Cormack lived:

With the coming of spring and early rains, the scent of lilacs filled the air and long pods of purple wisteria hung from luxuriant green foliage. Doors and lattice windows opened towards the courtyard to ensure a degree of privacy and quiet, but even the whoops and yells of passing Chinese, seeking to banish the evil spirits that surrounded the homes of the foreign devils, floated over the compound walls.

Rumours circulated that foreigners ate babies. Antiforeigner violence increased, and yet the missionaries stayed on, willing to die for ‘the Chinese’.

For readers interested in Chinese history, Rowlands’s book is a fascinating document. She outlines the complex political struggles in China at the start of the last century extremely well. Rowlands infuses historical material with personal reminiscences, which humanises the content and makes it accessible to the general reader.

Voluntary Exiles is a story of obsession. Rowlands’s forebears compulsively returned to their mission posts, with little apparent thought to how it affected their children. The children grew up, starved of affection, in English boarding schools. Generation after generation perpetuated this neglect. In some birds, Rowlands writes, the migratory impulse was stronger than the maternal. She cites Charles Darwin: ‘A mother may abandon her fledglings in the nest, rather than miss the long journey south with the rest of the flock.’

When saying goodbye to her parents, Joan Rowlands tried bravely to focus on her spinning top. Her sister cried, but she remained silent. ‘It would be years before I could cry,’ she writes. When her parents returned years later, the children did not recognise them. The fate of these children, abandoned by their parents, imbues the narrative with sadness. ‘There is no denying that the loss of their parents,’ Rowlands writes, ‘resulted in a profound diminution of confidence and self-esteem in the children, and even a feeling of responsibility in their abandonment.’

In the 1990s, a few memoirs about missionaries in China were published in Australia. Each of these books, written by women, describes missionary work within a highly resistant community. (After decades of missionary contact, China proved to be one of the least responsive of all Asian countries.) Dominating these narratives is the sense of adventure and independence. At this time, in the 1920s and 1930s, such independence would have been unthinkable at home. Missionaries experienced a higher social status when stationed abroad. Similarly, women were allowed a higher level of freedom.

Today, nearly 500,000 missionaries are working across the world. Joan Rowlands’s work, while focused on an earlier era allows us to understand why. She quotes a psalm as an epigraph; ‘By the waters of Babylon we sat down and wept: when we remembered thee, O Sion.’ From Papua New Guinea hill tribes to suburban railway stations, the question remains: ‘How shall we sing the Lord’s song in a strange land?’

Comments powered by CComment