- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Last Place to Love

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1941 the allied Western Desert Forces captured 130,000 Italian soldiers in Libya, the majority of whom were evacuated to Australia, India, South Africa and Ceylon. In 1943 Australia held 4668 Italian POWs. To increase agricultural production and relieve the shortage of manpower, the Australian government shipped a further 14,000 Italian soldiers from India during the course of the war, to be employed on farms throughout Australia. Britain was already employing over 40,000 Italian prisoners, housed in central camps and working under supervision. With greater distances and fewer resources, the Australian government decentralised their operation, placing Italian prisoners on private farms, unguarded, under the authority of local Control Centres.

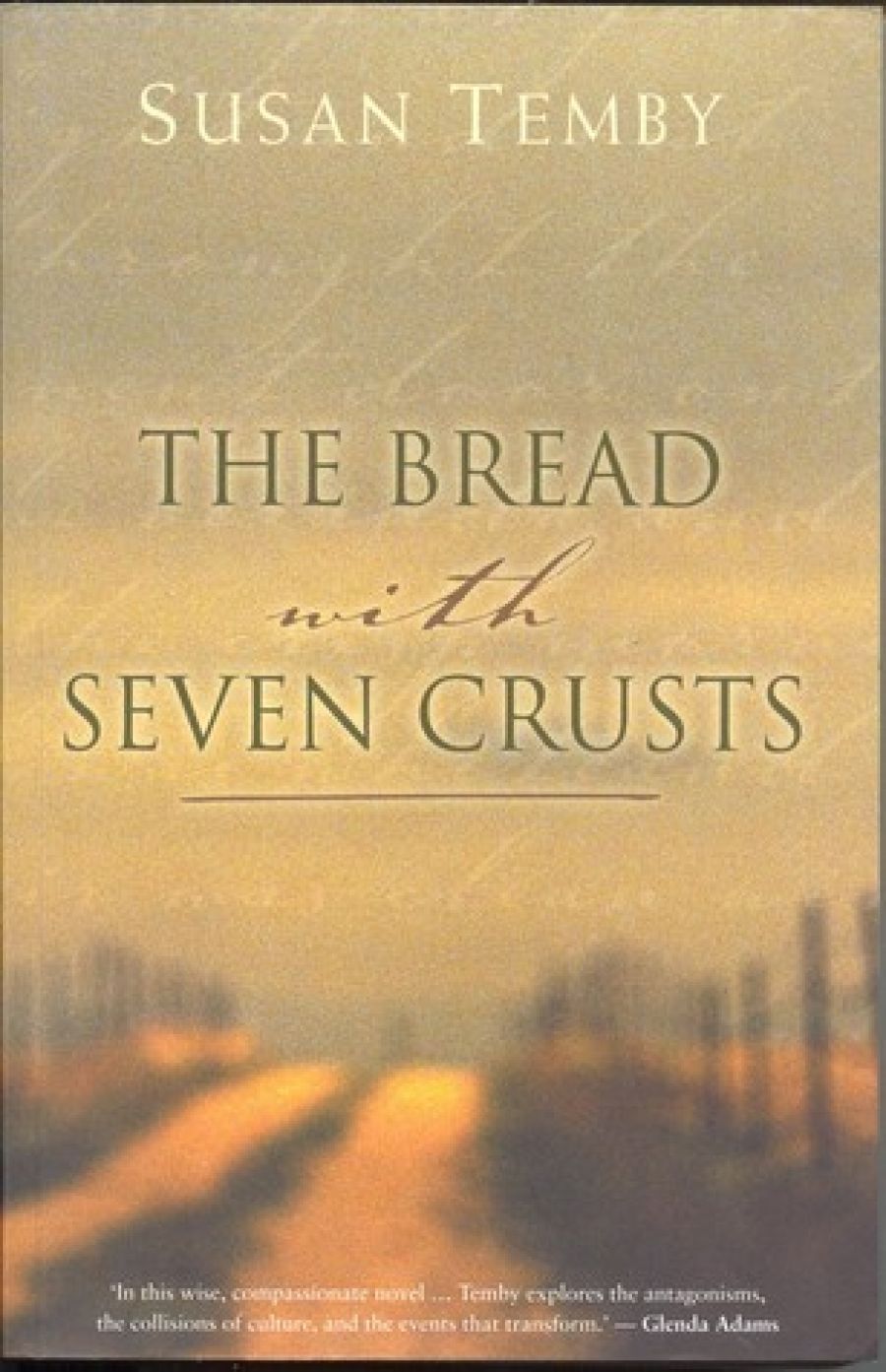

- Book 1 Title: The Bread with Seven Crusts

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $27.95 pb, 448 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

There was no publicity for this scheme during the war and not much attention given to it afterwards. Susan Temby has carefully researched this part of Australia’s wartime history, and uses it as the foundation for her first published novel. The Bread with Seven Crusts is primarily the story of the relationship between Giuseppe Lazaro, an Italian POW, and Eddy Nash, an Australian nurse. Eddy’s brother Max and her mother, Mrs Nash, employ three POWs, Giuseppe, Vincenzo and Carlo. The men have been transported from a camp in Melbourne to the Nash farm in Western Australia, ‘the last place God would ever love’. Just as everyone is settling in, Eddy, who has been nursing in New Guinea, arrives home. For Eddy, ‘[c]oming home after four years of service as an army nurse was like falling overboard from an ocean liner in the dark and watching it steam heedlessly away’. She struggles to adjust to family life and is particularly resentful of the hospitality shown to the POWs. She’s a moody girl, but Giuseppe is a good-looking, hard-working, intelligent fellow, and a relationship grows between the pair.

Whilst Giuseppe and Eddy are falling in love, Temby delivers some background on the Nashes and gives us an overview of an Australian rural community in the 1940s through a range of events, including a bushfire, a dance, a funeral and a storm.

Eddy is assigned to a hospital and her letters to Giuseppe raise suspicions. Max sends Giuseppe away from the farm, but their relationship continues. As the war draws to an end, Eddy and Giuseppe are forced to make decisions about their future together. The final section of the book, ‘Martyr’, unravels the consequences of their decisions, and as the heading suggests, it isn’t all good news.

The Bread with Seven Crusts is an earnest book that tackles some rich and interesting themes. You can see the potential in Temby’s novel, at times you can even feel it straining through the writing, but it remains unrealised. Temby covers a decent range of issues, obtaining good mileage from her material, and her depiction of Australia during World War II is convincing. She deals with war as a crucible, particularly in the lives of women; the unrelenting grind of poverty in rural Australia; the tensions of cross-cultural relationships; the guilt and retribution of postwar marriages; the acceptance and experience of migrants in Australia, and the experience of exile and imprisonment.

However, Temby’s writing flattens these strong, engaging themes. There are some good moments, such as Lizzie Harmer’s suicide and bush funeral, and Temby’s experience in the theatre has given her a good ear for dialogue, but, on the whole, the book is unfulfilled. The narrator has a strangle-hold on the characters, telling us rather than showing us who they are. Eventually, they feel like cut-outs stuck on a cardboard set. And they tend to ‘growl’ at each other a lot. Techniques such as changes in the point of view and shifting tenses don’t create the immediacy, empathy or poignancy I suspect they are intended to. The many chapter headings are literal or obscure, and the writing is often stiff, with a frustratingly apologetic undertone. ‘When she thought of Giuseppe, her skin began to sting as though she had been flayed, however that felt. She had skinned her knees often enough as a child, so she imagined it felt like that all over.’ Either you feel like you have been flayed, or you don’t. And similarly: ‘He dreams that he kills Hal and when he wakes he feels happy. Then he remembers the dream and wonders about his criminal subconscious.’ He wasn’t the only one. The novel would have been much better for demonstrating these moments rather than baldly articulating them.

Over 448 pages, these flaws became greater than the sum of their parts. This is a book with good intentions, but it left me feeling exhausted. HarperCollins suggests this novel ‘marks the arrival of a major new voice in Australian fiction’. Blurbs should be optimistic but, on this occasion, I think they have overstated the case.

Comments powered by CComment