- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Settler Colonialism

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Two Witnesses

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The reissue by Magabala of the late David Mowaljarlai and Jutta Malnic’s Yorro Yorro coincided with the publication of Andrew McMillan’s An Intruder’s Guide to East Arnhem Land. These radically different books address cultural exchange between Aboriginal and settler cultures. On one level a banal travelogue, Yorro Yorro is transfigured by the language and stories of Mowaljarlai, and fits, to an extent, into romantic discourses about indigenous people. It is no surprise that it is published in the USA by Inner Traditions International, a leading publisher of books on indigenous cultures and self-development. An Intruder’s Guide is a more sober piece of writing: McMillan combines textured descriptions of Yolgnu politics and life with dry but lucid historical narrative.

- Book 1 Title: An Intruder’s Guide to East Arnhem Land

- Book 1 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $22 pb, 342 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Yorro Yorro

- Book 2 Subtitle: Spirit of the Kimberley

- Book 2 Biblio: Magabala, $32.95 pb, 252 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Yorro Yorro has its origins in those halcyon days of the Australia Council when there was ample arts funding, and Australia Council staffers seemed able to make on-the-spot decisions about funding. One day in 1980, an Australia Council officer rang Jutta Malnic, a photographer, with the news: ‘Guess what, Mowaljarlai’s just been here in my office. He wants some rock painting sites photographed. I said we’d do it.’ David Mowaljarlai was a charismatic, if sometimes controversial, Ngarinyin elder from the Kimberley. In one nationally publicised event in the 1980s, he supervised a group of Aboriginal youths in the restoration of a Kimberley rock art site. As I recall, the re-painting, carried out with acrylics and featuring non-traditional motifs, was unanimously criticised. Given Mowaljarlai’s concerns about the desperate plight of many Aboriginal youth, he may well have felt that this act of cultural renewal and maintenance, as he saw it, was justified.

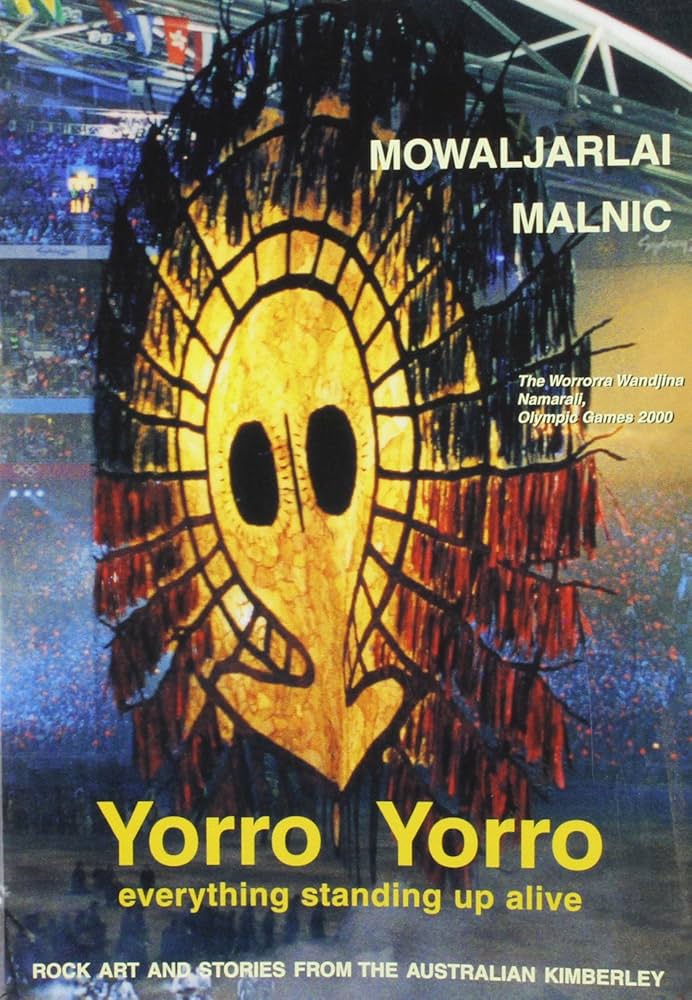

Malnic travelled with Mowaljarlai through the Kimberley in search of Lejmorro, ‘the boss site of the Wandjina paintings’. Mowaljarlai explained that Lejmorro is the earthly manifestation of the Milky Way and, in a characteristic homology, related Lejmorro to humankind: ‘We carry the light in us and shed it onto others by teaching. Everything has two witnesses, one on earth and one in the sky.’ Photographs of Wandjina paintings peer from the pages of Yorro Yorro, and the cover of the new edition features the Wandjina image from the opening ceremony of the Sydney Olympics. All testify to Mowaljarlai’s belief in the universal aspects of Aboriginal culture. But, in a salutary reminder for the reader inclined to take a transcendentalist, ahistorical approach to Aboriginal culture, he wrote: ‘I am grog and despair am sickness and early death. And the Wandjina can’t walk in jails.’

The new edition of Yorro Yorro features a dialogue between Mowaljarlai and Malnic on the ‘Bradshaw Figures’, enigmatic rock paintings found in the Kimberley. Of great antiquity, the figures have been the object of fantastic speculations as to their origin, with some writers suggesting a primordial African connection. Mowaljarlai, however, provides detailed information that, for the lay person, seems to prove the Aboriginal origins of the paintings.

As well as the stories and teachings Mowaljarlai shared with Malnic on their expeditions in search of Lejmorro, he also revealed his prophetic dreams. Malnic was taken aback but dutifully recorded these visions, and they are among the most sapient elements in Yorro Yorro, subtle reinterpretations of Christianity that draw on aspects of the Aboriginal tradition: ‘And I know now that God comes from the sunrise, where power comes from. He comes from the same direction that the Wandjina came from. Power comes from an angle, not from straight above – that is my statement.’

Unfortunately, Yorro Yorro is by no means reader-friendly. Malnic employs a staccato style to represent the immediacy of her experiences and reactions. At times it reads like an annoying and petty narrative of the discomforts of travel, in which the reader occasionally encounters Mowaljarlai’s voice. There are other disquieting elements. Malnic has an accident before setting out with Mowaljarlai in search of Lejmorro. Later, as they approach Lejmorro, Mowaljarlai becomes uncharacteristically disoriented and the party take shelter in a cave from an approaching fire before turning back. Before leaving for a later trip with Mowaljarlai, she sprains an ankle. This leaves the reader with an unsettling feeling that Malnic was being warned off, and that aspects of the project ran contrary to the nature of Aboriginal spirituality.

In comparison to Malnic, McMillan is a less demanding companion, and thus travels more comfortably. This is reflected in his book. An Intruder’s Guide to East Arnhem Land covers much territory, but McMillan remains a self-effacing presence. McMillan began his journey into East Arnhem on the trail of the Warumpi Band’s 1985 Big Name No Blankets tour of Aboriginal desert communities. A year later, he entertained Mandawuy Yunupingu and other Yolgnu men in his squat in Sydney. An ongoing connection is established, founded initially on rock music and an easygoing rock life-style, replete with omnipresent cans of beer, bilma (tapping sticks) and guitars. McMillan fits comfortably into life on a Yolgnu outstation, and deals lightly with some of the anti-romantic contradictions of contemporary Yolgnu life: he is shocked when his Yolgnu hosts casually kill a turtle – even though food is plentiful and easily found — and take turtle eggs from an island that, under Aboriginal law, is temporarily off-limits. But he doesn’t dwell on his own sensibilities to the detriment of his narrative. In some ways he is like one of his predecessors, Donald Thompson, the anthropologist who also travelled lightly – like McMillan, walking barefoot through East Arnhem Land.

McMillan has a particular gift for evoking the everydayness of Yolgnu life, whether it’s the breakfasts of billy tea, damper and crayfish served at an outstation, or the squally late monsoon weather. But he also provides an immense amount of information on Yolgnu beliefs, Yolgnu politics, contact history and contemporary Yolgnu life.

In his Introduction, Mandawuy Yunupingu describes An Intruder’s Guide as a book dealing with cross-cultural contact. Yunupingu tells of an early group of settlers, the Bayini, a golden-skinned people who, following Yolgnu protocols, settled peacefully in their lands in some immemorial past. No archaeological evidence has ever been found, but memories of the Bayini are still preserved in Yolgnu songs, just as conclusive proof of contact with Macassan trepangers is still preserved in Yolgnu culture and language. The Bayini were ‘the first of the intruders’, but nothing in these early encounters had prepared the Yolgnu for the whitemen. They came in waves: gold miners, trepangers, odd adventurers, cattlemen and finally Christians.

The ability of Aboriginal communities to resist is sometimes romanticised, with destructive and maladaptive forms of behaviour taken as evidence of resistance. In An Intruder’s Guide, optimism and cultural pride run parallel with lawlessness and anomie. But it also has much to say about cultural exchange, in particular the manner in which Yolgnu society has been able to maintain its integrity while borrowing from other cultures. Settler Australians who frighten themselves about Muslim immigrants might be surprised to learn from An Intruder’s Guide that 400 words of Macassan origin are still found in the Yolgnu language and that praises to Allah are spoken during ceremonies.

Comments powered by CComment