- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hard Labour

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If Cheryl Kernot writes another book – and if Speaking for Myself Again is anything to go by, you had better hope she doesn’t – her publishers should at the very least make sure the punctuation police do their job. It appears they didn’t even show up to the scene of the accident this time. Exclamation marks are strewn throughout the work. Each time Kernot wants to bitterly labour a point, up pops an exclamation mark, as if she’s hitting the keyboard and cursing, ‘Take that you bastards’. Thus we get: ‘And some people can be so rude!’; ‘Women have sustained me!’; ‘I could write a whole book on my experiences with the media. Perhaps I will!’; and ‘Opinion rules!’ In a teen diary, that’s fine, but not in a book by a former senior federal parliamentarian.

- Book 1 Title: Franca

- Book 1 Subtitle: My story

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $29.95 pb, 327 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

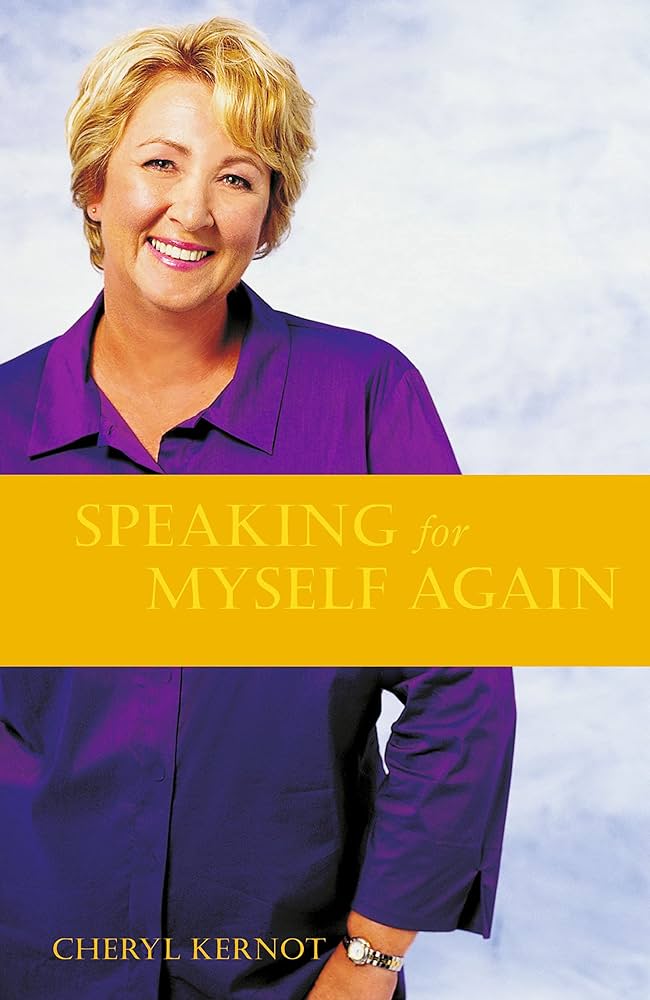

- Book 2 Title: Speaking for Myself Again

- Book 2 Subtitle: Four years with Labor and beyond

- Book 2 Biblio: HarperCollins, $29.95 pb, 288 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Then again, any hope this work had of being taken seriously was snuffed out by the post-publication revelations. Speaking for Myself Again was touted as a ‘revealing memoir’ of a leading Australian politician who had an ideological epiphany and switched parties – from the Democrats to the ALP. Good storyline so far. It’s not every day politicians turn their coats. However, Kernot left out the love twist. Apparently, this was none of our business because it hadn’t influenced her decision to switch parties. Love in Canberra must be of the cold fish variety.

Never mind. If the omission bothers you, staple the relevant newspaper clippings to the book’s pages. But what can be done about the book’s other big problem – the writing? It barely rises to mediocrity, so unskilled is it. At best, it has a sort of bureaucratic orderliness of thought, with a matching vocabulary: empty-sounding, yet formal. You expect ugly, committee-made words such as ‘detribalised’, ‘disempowered’ and ‘re-empower’ to get a run, and they do. On page 213, Kernot preaches, ‘Let us rise above lazy rhetoric and clichés’, something she has failed to do throughout her book. Two pages later, she shows just how rhetoric and clichés are done as she holds forth on the subject of courageous leadership:

It’s about the courage to take responsibility for the long term. It’s one thing to talk about intergenerational equity, it’s another to do something about it … It’s about action now to deal with global warming and clean rivers and oceans and endangered species. It’s about poverty and generosity. It’s about our common humanity.

That’s about as deep as the book gets on policy matters. If, when speaking for herself, this is the best she can do, perhaps Kernot should consider ventriloquism.

Much of Kernot’s prose pants with exasperation and petulance, and soon resorts to flippancy. She may well have worthy insights into the male-supremacist media and political system – she rails against the former’s lust for trivia and the latter’s factional tribalism – but the book’s stylistic inadequacies wither the reader’s faith in her authority.

Memoir, or life-writing, to use its academic title, is all the rage at present, the publishing equivalent of Reality TV. When that book is a Celebrity Memoir, you don’t expect to find much polish in the work. But I’m sure there’s a limit to what an intelligent reader can take. This book may well have reached it. After all, Kernot says at one stage: ‘My experience is that written words do not capture emphasis and irony.’ Her written words certainly don’t.

From the outset of Franca Arena’s life-writing effort, Franca, it’s obvious that this author can speak for herself attractively and in a direct, no-frills manner. Briskly, she marches us through her memories of childhood and adolescence, providing plenty of evocative detail as she goes: the bleakly beautiful apartment blocks of Genoa, where she was raised; the city’s strict Catholic caste system. They form the gloomy atmosphere of Arena’s early life: her brutal father; her mother, who runs off to Argentina with a lover, abandoning her children for good. With material like this, how can you go wrong? It makes compelling reading. Arena’s emotional memory does not flood the telling with tears and wallowing, but the whole horror makes for a wrenching read.

Later, she takes us on a personal tour of Australian multicultural politics. She emigrated here in 1959 as a young woman, fetching up at the Bonegilla migrant camp near Albury, a forerunner of today’s detention centres, complete with Dantesque graffiti at the entrance: ‘Bonegilla a place of no hope,’ says Arena. ‘The suffering and powerlessness I saw at Bonegilla wakened my social conscience.’ It was the genesis of her political life.

Arena was an ALP parliamentarian in New South Wales from 1981 to 1997, and an independent member for two years after that. Her book’s tour through ALP politics from the 1970s onwards has a density of experience and observation that makes Kernot’s overview of similar subjects – the ruthless boy’s club with vengeful factions and five-minute loyalties – seem trite.

If Arena is remembered, it will be as the woman who didn’t think the Wood Royal Commission, established in 1994 to investigate NSW paedophile networks, had been rigorous. She believed she had evidence that there were high-ranking citizens who were paedophiles known to, and protected by, the police. In a speech in parliament in October 1996, she posed the question: Was the Commission investigating certain prominent people, including Supreme Court Judge David Yeldham? Soon after, Yeldham committed suicide. But was he actually a paedophile? A Commission report quotes Yeldham admitting to frequenting public male toilets for rough trade sex with ‘persons of whose age he made no inquiries’. That doesn’t make him a paedophile.

To many gay rights activists, Arena is a poisonous homophobe, incapable of distinguishing between paedophilia and homosexuality. The twist here is that Arena’s two sons are both gay. Arena is quite the libertarian on republican issues, feminism, you name it. However there’s nothing like sex to bring out the conservative in a person. ‘Some people thought we should celebrate the fact that our sons were homosexual, but to my husband and me it really was a cause for sorrow and nothing will ever change that,’ she writes. It’s something to do with wanting grandchildren and worrying that her boys might get AIDS.

When Arena left politics, she was hated by some – the gay rights lobby – and admired by others – the Fred Nile-ists. But at least, unlike Kernot, Arena has written a memoir that is meaningful and self-investigative enough to convince readers that they have got the writer’s full story.

Comments powered by CComment