- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cricket

- Custom Article Title: Postcards from Mark

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Postcards from Mark

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This summer, browsers will probably find these chronicles of Eddie Gilbert and Mark Waugh snuggled close together in bookshops. Both, after all, are biographies of Australian cricketers, written by journalists, and published by firms with strong sporting backlists. But their proximity will be misleading. Cricket contains few less similar careers, and has generated few more different narrative styles. Indeed, reading them consecutively is to appreciate how stealthily our understanding of ‘biography’ has been elasticised.

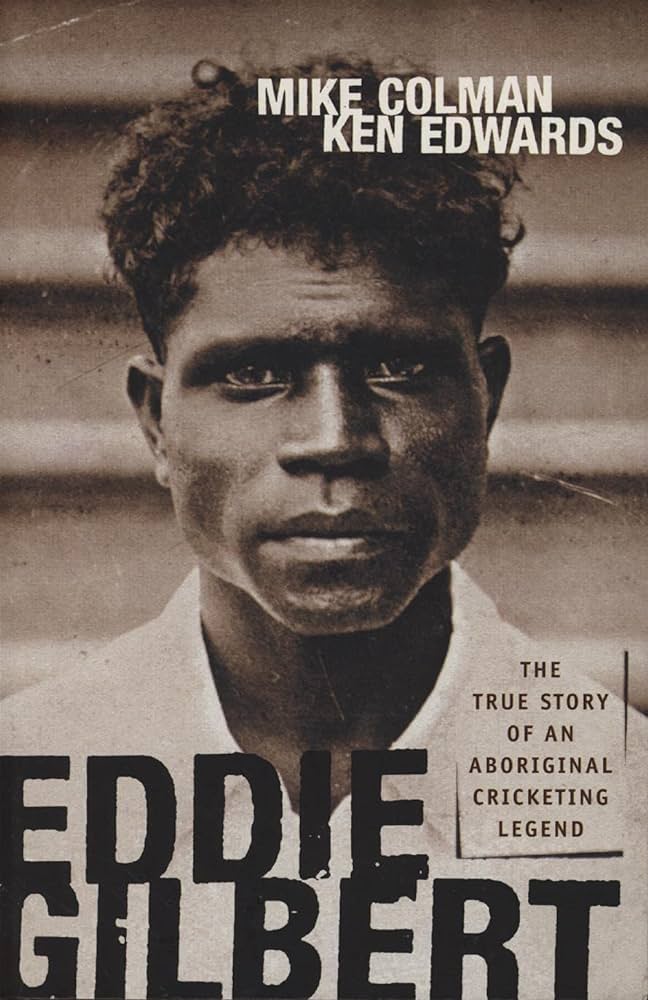

- Book 1 Title: Eddie Gilbert

- Book 1 Subtitle: The true story of an Aboriginal cricketing legend

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $29.95 pb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

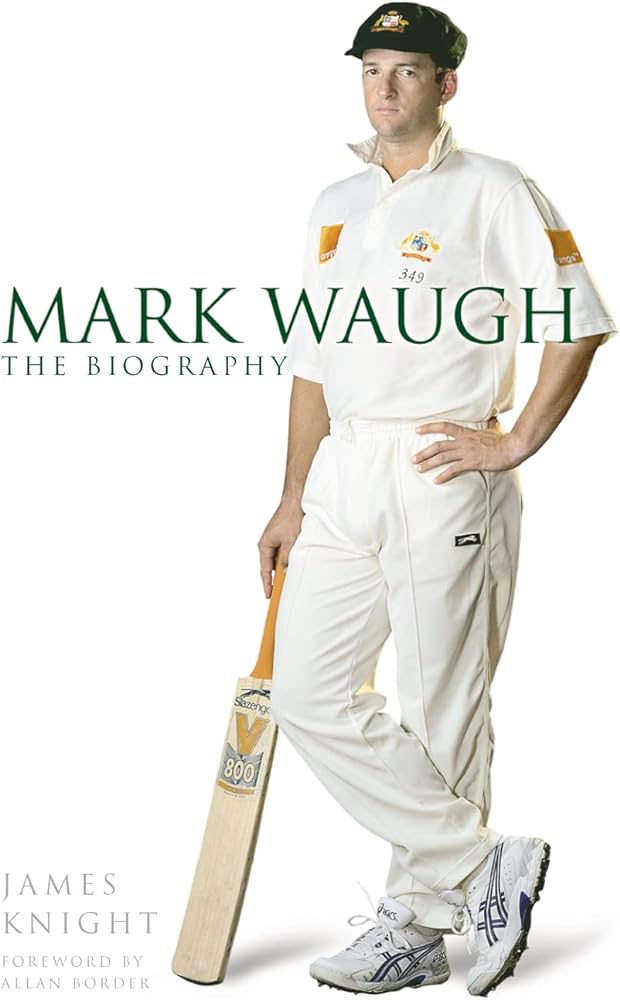

- Book 2 Title: Mark Waugh

- Book 2 Subtitle: The biography

- Book 2 Biblio: HarperSports, $36.95 hb, 398 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The book really belongs to Edwards, a lecturer at Queensland University of Technology, who spent seven years researching Gilbert’s story for a PhD. Grasping an idea that some academics seem to find elusive – that a thesis is no more a book than a lump of wood is a cricket bat – he then had the work rewritten in an accessible but analytical style by Colman, a Courier-Mail columnist. The result is a distinct Australian rarity: a book about sport that is both readable and rigorous. Edwards has had access to settlement records and correspondence, has interviewed widely among Gilbert’s indigenous contemporaries, former team-mates and rivals, and has flinched from nothing.

Gilbert was a freakish cricketer, handicapped by a lack of stamina, and eventually tainted by suspicions about the legality of his action, but probably faster than any Australian bowler at the time, and, at least in his home state, a popular hero. Not surprisingly, his story has been encrusted by legend and lore. There’s much to admire about the authors’ methodical approach to distinguishing fact from fancy. Old stories that have achieved permanence through repetition, such as Gilbert’s living in a tent in the garden of a Queensland Cricket Association official, are proven false. Edwards’s research would have been improved only by a comparison between responses to Gilbert and representations of other black athletes of the period, which might have been illuminating. The stories of Gilbert’s bowling barefoot, which Edwards concludes are untrue, seem to echo the tale of ‘Float’ Woods pleading with his West Indian captain in 1900 to let him ‘feel de pitch wid de toe’.

The weaknesses of Eddie Gilbert are to be found in the prose. There are some contestable judgments (‘To the majority of Australians in the early 1900s, sport was seen as fun, a diverting pastime’) and some avoidable clichés (‘His word was law and it was a law he policed with an iron fist’). At perhaps the pivotal point, Gilbert’s defeat of the Don for a duck in November 1931 (reported as a kind of imagined re-creation straight out of Creative Writing 101), the narrative loses shape and form. These are, however, relatively rare lapses. For the most part, Colman does his wordsmithing with unobtrusive competence.

On one level, Eddie Gilbert will not, and probably could not, satisfy. A quiet man who left little impression on contemporaries save his speed, and whose recorded remarks were restricted to a few corner-of-the-mouth confidences to journalists, he remains an elusive subject. This, nevertheless, matters less than it might: the reactions to Gilbert are probably as instructive as anything he might have said or thought. A subject’s cooperation, furthermore, does not guarantee noteworthy biography, as may be deduced from James Knight’s Mark Waugh. This is one of those ‘authorised biographies’ that currently abound in sport, and are increasingly popular among other demi-celebs. They are, essentially, slightly modified autobiographies, in which the ghost writer hardens from ectoplasm into slightly more palpable form as a narrator, while the subject’s views are interposed as quotations rather than revealed in the first person. With further quotations from others tactfully scattered throughout the text, this suggests a conventional arms-length biographical portrait; in fact, the views are carefully bowdlerised and sanitised so as to show the subject in the best possible light.

There’s no cause for alarm. Buying memoirs by modern sportsmen is like making a donation to their testimonial fund and being given a free book as a receipt, not so much to read, but to symbolise your allegiance. Even by genre standards, however, Mark Waugh is remarkably charmless. Knight is a mediocre writer (‘Young. It was the most fitting way to describe Mark before his first Sheffield Shield match’); worse, he’s a mediocre writer with a flair for the ornate (‘Nowadays, one-day matches are like confetti – the brilliance they offer for a fleeting moment or two generally becomes nothing more than scraps flicked from the memories of players’). His attempts to describe places are buttock-clenchingly bad: ‘There is a touch of “The Man From Ironbark” about Jalandhar, for in this Sikh town “flowing beards are all the go”. So too the brilliantly coloured turbans that are matched only by the dazzling smiles of the people.’

The world according to Knight, in fact, divides roughly into those places that are poor and happy like Sri Lanka (‘Despite the sadness, communities continue to smile with a warmth that hovers well above the temperature in this equatorial and political hotspot’) or the West Indies (‘The region is poor, yet the people are rich in character and warmth’), and those that are poor and bearded like Pakistan (‘Men with flowing beards kneel in prayer. A bus belches filthy black smoke ... This is Pakistan, the toughest country for an Australian cricketer to tour’). Not that Mark Waugh’s travels are much influenced by either smiles or beards: when on tour, we learn, he seldom leaves hotels, takes no photographs, and finds the foreigners, well, a bit on the whiffy side; ‘it’s a bit off putting having a bloke standing next to you with a gun, but ... actually their body odour is more unsettling’. Fortunately, Third World folk generally know their place: ‘We know we’re in a privileged position when we go there because people just want to worship us and treat us like kings.’

Not all of the 380 pages here can be cribbed from the postcards on Knight’s fridge, so readers must grind their way through Waugh’s career, innings by innings. The effect is repetitive at best; inane at worst. It is a curious sensation to read Mark Waugh immediately after Eddie Gilbert – the effect of passing from a subject who talked so little yet said so much, to one who talks so much and says so little.

Comments powered by CComment