- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Picture Books

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Quintent of Bestiaries

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What do these five picture books have in common? Well, they are all about animals, but they range from pre-school books such as Shutting the Chooks in, through middle primary with Gezani and the Tricky Baboon, to books for older readers such as I Saw Nothing. They also vary generically: The Elephants’ Big Day Out and Sherlock Bones are fantasies, Gezani and the Tricky Baboon is a retelling of an African folk tale, and the other two are realistic stories.

- Book 1 Title: Sherlock Bones

- Book 1 Biblio: Lothian, $26.95 hb, 32 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

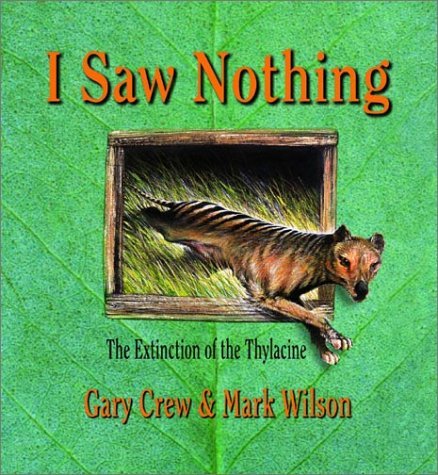

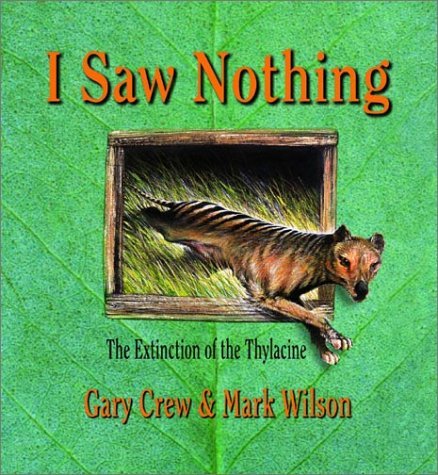

- Book 2 Title: I Saw Nothing

- Book 2 Subtitle: The extinction of the thylacine

- Book 2 Biblio: Lothian, $26.95 hb, 32 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Shutting the Chooks in

- Book 3 Biblio: Scholastic, $26.95 hb, 32pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Fantasy is never as easy to write as one imagines. It needs its own logic such that, within the parameters of the story, everything appears perfectly reasonable and convincing. Here the reason the elephants are easily able to leap out of their cage or why the zoo gates are standing open in the middle of the night is never explained. For all that, some of Elise Hurst’s illustrations are excellent, particularly a page showing the three elephants dancing up a street in the moonlight, or a double spread of them gazing at Luna Park from the top of the tourist bus.

Sherlock Bones is a dog with a moustache, deerstalker hat and attitude. When Dad’s car keys go missing, it is Bones, equipped with a metal detector, who finds them. Perish the thought that he also buried them in the first place, piqued perhaps by Dad’s constant remarks about his dumbness: ‘If Bones is so clever how come he hasn’t found my keys?’ These remarks are handwritten by the narrator, Bones’s owner, and accompanied by crayon drawings of a full-length, perpetually angry Dad. Elsewhere, only Dad’s lower half appears, bulging trouser-belt downwards.

This is a fantasy that works. It’s written, illustrated and, one suspects, designed by Connah Brecon, so there is a unity about the whole book, from the front jacket, on which Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s name has been crossed out and replaced with Brecon’s own, to the dedication on the final page: ‘for whoever … oh yeah, Ma and Pa …’ It’s for older children who will enjoy the Sherlock Holmes jokes such as the book entitled A Stubby in Scarlet, or the self-portraits on the inside covers: at the front, a crayon sketch of the narrator with ‘This is Me’ scribbled beneath; and, at the back, a handsome oil painting of Bones inscribed ‘C’est Moi’.

Folk tales may be fantastical, but essentially they are oral stories handed down through the generations. In Gezani and the Tricky Baboon, Valanga Khoza retells a story from her African childhood. Gezani is asked by his grandfather to take a bunch of bananas to his cousins on the hill. Gezani sets off eagerly, bananas in a bowl on his head. Before long, he is joined by a baboon. Soon the baboon begins to limp and to complain about his thirst until Gezani agrees to go to the waterhole for him, leaving the bananas in the baboon’s care. This is not a good idea, but Gezani thinks up a way of getting his own back.

There is an entirely convincing matter-of-factness about the fantasy element. The baboon simply steps out of the jungle and says: ‘Hello, Gezani … Those bananas look very heavy. Can I help you carry them?’ The story is punctuated by variations of a song that Gezani chants as he walks along: ‘Bananas, bananas, bananas on my head, /Bananas, bananas, if you’re hungry you’ll be fed.’ Sally Rippin’s pictures are simple – a blue baboon and a small brown Gezani set against different-coloured pages – and yet the book doesn’t quite work. There is a surprisingly old-fashioned feel to it, with its squat square format, coloured pages and simple blocks of illustration, and the actual story is a mite disappointing in that Gezani never reaches his cousins with the bananas.

The last two books are realistic stories, about things that could, or did, happen. In Gary Crew’s story I Saw Nothing, the storyteller is a girl who is out feeding the hens when Elias Churchill arrives looking for her father, and sees a live ‘tiger-wolf’ trussed up on the horse behind him. Later, after her father is killed in a logging accident, she and her mother sell up and move to Hobart. One day, she wanders into the zoo, a rundown place, and sees the thylacine: ‘Pacing up and down inside the wire. Pacing and moaning. Up and down. All alone.’ A year later, it is dead and, belatedly, thylacines are declared a protected species.

This story suits Crew’s style. It’s powerful, moving and told, at times, with the economy of a poet. Mark Wilson’s pictures remind me of Robert Ingpen’s work, both in their suffusion of light and in the way the pictures often stand alone, independent of text. At the last opening, for example, when the narrator reads of the thylacine’s death, the full-page picture opposite shows the tiger-wolf racing down a hillside under a full moon. Most of Wilson’s paintings are beautiful, particularly those of the bush, but one of ghostly figures suspended in the night sky left me slightly squirming with embarrassment.

Libby Gleeson’s story, Shutting the Chooks in, is about exactly that. The problem is that one chook is missing and the boy has to go back through the darkening orchard to the engine sheds to look for her. The text is pared right back to a minimum, so that every word counts: ‘Night is coming. /Fox is out there. / Sharp eyed, / slavering mouth, / quick to leap.’ This gives a sense of urgency and vividness to what is quite a slight story of ‘there and back again’.

Ann James has used oil pastels and charcoal for soft big pictures that fill the whole page. The story depends on the boy’s shifting moods to generate interest. With a minimum of fuss, James portrays him confidently skipping along through the orchard in front of the striding chooks and then returning the same way, his whole body twisted with anxiety and worry. She has taken care of every bit of space so that the front endpaper, for example, shows the boy on his outward journey, the sky suffused with pink from the setting sun, while the back one reveals his return journey, the boy running hard through the gathering night.

Comments powered by CComment