- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Unexpected Finds

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The fourth issue in the new series of Heat, Burnt Ground, reproduces on the cover a segment of a beautiful watercolour by John Wolseley, wrought from his six-month stay in Sydney’s fire-flattened Royal National Park in early 2002. Along with many noteworthy contributions, a further eighteen colour pages of Wolseley’s lush sketches, entitled ‘Bushfire Journals’, make it an issue to treasure. Wolseley has written a diary to accompany his pictures, which tells us how ‘new shoots at the base of many of the burnt shrubs … spume out of their black bases like an army of bunsen burners’, and also illumines his unorthodox approach. With the help of a friend, he rubbed a vast roll of paper along the trees and over the ground: ‘a Banksia[’s] …sooty knobbly bark left a passage of black scales on the paper as if a huge reptile had moved over it.’ Wolseley’s narrative is more uneven than his sketches, but offers valuable insights into the way a painter digests and regurgitates his chosen material.

- Book 1 Title: HEAT 4

- Book 1 Subtitle: Burnt ground

- Book 1 Biblio: $23.95, 239 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Meanjin

- Book 2 Subtitle: Reads their lips

- Book 2 Biblio: $19.95, 234 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Murray Bail also renders the workings of an artist’s mind in a direct and spare manner that echoes the paintings of his subject, the New Zealander Colin McCahon. Written for the catalogue to an exhibition of McCahon’s works, which opened in Amsterdam and will travel to Australia, the essay is divided into fourteen tiny chapters and reads like a short story about an obdurate man who remains true to his faith, and is driven to reflect that conviction in his paintings; paintings that were often derided and misunderstood (particularly in the 1960s), resulting in his isolation and, perhaps, in his heavy drinking. McCahon’s dark landscapes also remain faithful, as Bail de-scribes it, to ‘the land of the long black shadow’, where sunlight is muted and black is the national colour. This fine piece shows that when writers such as Bail tackle art criticism they can make apparently ‘difficult’ works seem perfectly intelligible to the layperson. I for one will be lining up to see the McCahon exhibition when it arrives.

Heat is not the only journal to feature persuasive contributions on art: in Meanjin Reads Their Lips, Christopher Heathcote has written a pellucid review of The Solitary Watcher: Rick Amor and His Art, by the late Gary Catalano. Amor, it would seem, learnt well from his mentor at art school, John Brack, whose maxim is worth repeating here: ‘you are not an artist if you cannot find a lifetime’s work within a mile of your frontdoor.’ Heathcote’s view that this book is ‘fresh and enjoyable to read … [and] perceptively informative’, is amply supported by the preceding essay in which Catalano (in one of the last pieces he wrote before his death) discusses the importance of home in Les Murray’s poetry – from both, it is evident that Catalano contributed a great deal to Australian art and literature.

Meanjin offers readers a broad range of topics, so from art we plunge straight into politics with an interview entitled ‘Who’s Liberal? What’s Liberal?’ in which Malcolm Fraser confounds contemporary notions, as put about by John Howard, of what it is to be Liberal. To this reviewer (who has been out of the country for some time), it is a surprise to find him quietly demonstrating the very sane point of view that: ‘once the practice of discrimination is accepted, as it has been by this government and by the opposition, there’s no telling where it might end.’ Speaking in September 2002, he proves himself to have a canny political grasp, too. Asked for his views on the near future, he predicts that the US is certain to attack Iraq, albeit without European involvement, with the possible exception of Tony Blair.

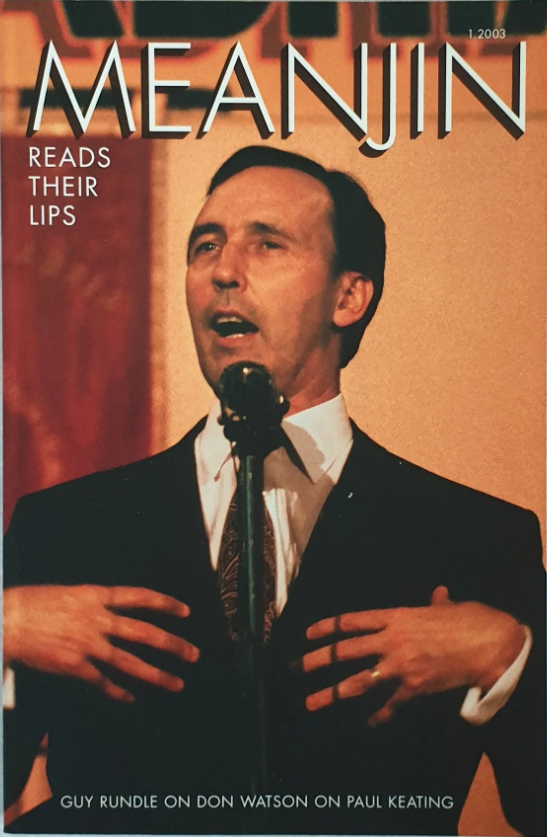

If political leadership is about ‘having an idea of where you think Australia ought to be in twenty-five years’ time’, as Fraser sees it, then Paul Keating, one would have thought, was exemplary. Yet Guy Rundle’s rousing review of Don Watson’s memoir/biography of Keating suggests that the reality was more complex. As a leader, Keating was astute, authoritative and charismatic, but also prone to a good sulk, having procured the top job just when he might have preferred to indulge a mid-life crisis. Keating adorns the journal’s cover, mid-rhetoric, hands eloquently placed on his lapels, looking much like the character Rundle memorably ascribes to him: ‘between Iago, Büchner’s Danton and Basil Fawlty.’

Meanjin also includes a review by Tim Rowse of the recent biographies of John Gorton and Jim Cairns. Rowse argues that, contrary to popular belief, it is possible to separate the public from the personal. This is followed by Peter Karmel’s rationalistic take on Rowse’s own biography of ‘Nugget’ Coombs, a somewhat cosy conjunction that doesn’t detract from the piece. The political content of this issue is distinguished by its clarity and pep, and overall Meanjin is to be valued for its enjoyably long critical essays, as well as its interviews. Its poetry and fiction, however, are a little less reliable. Of the nine poems here, only two cut any sort of mustard. Perhaps it depends on what you think poetry should do: communicate or obfuscate. Some of these authors seem to be writing long strings of words to themselves, chopping them up with little notion of rhyme, metre or substance. I find it hard to discern anything meaningful in twenty-five lines to the tune of, for instance: ‘ … marble in green / the rusted ascent she / views the LZ flared & nothing below / to walk the rimy stone.’ Among the short-story writers, both Pat Skinner and Kalinda Ashton evoke well the fragile moments on which life turns.

Given that Heat’s raison d’être nowadays is its prose and poetry, it is cheering to report that, of the fifteen poems and seven items of fiction in this issue, most are a pleasure to read. Particularly engrossing is the story by Alai, the editor-in-chief of a sci-fi magazine in China, though this piece is firmly rooted on planet earth. As it unfolds, a Tibetan is seen to be as much a fish out of water as the hundreds of fish that he breaks a religious taboo to catch, during a pit stop on a journey through a marshy prairie with some Han Chinese colleagues. When the fish start ‘queuing up to die’, the narrator cannot resist hauling them out even as doing so fills him (and the reader) with horror. Howard Greenblatt has skilfully translated this story. Authors from China to India (Siddhartha Deb), to Israel (Etgar Keret), alongside Eva Sallis’s story ‘Flight’, set in Iraq, give the journal a cosmopolitan edge; and it is always a treat to encounter compelling new writers. For me, Maria Zajkowski is also one of these, a Melbourne poet whose depiction of loneliness in a suburban backyard catches at the heart, as are Anna Jackson and Jane Williams.

Each journal contains an unexpected find. In Heat, Jill Hellyer’s account of the death of her deaf and almost-blind 45-year-old son on the railway tracks in Perth is shocking, but it also challenges our sometimes sanitised view of disabled people. It is admirably and unselfconsciously told. Meanjin’s more oddball item is by Alec McHoul and Mark Rapley, who argue that the price of ‘shutting up’ about madness, as ruthlessly pursued by the mental health watchdog SANE, undoubtedly with the best of intentions, will be the loss of a rich and flexible vocabulary. SANE’s list of tendentious words includes depressed, compulsive, obsessive, fruitcake, loony, nutter and probably oddball. I can’t imagine getting through life without them.

Comments powered by CComment