- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Independent Duo

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

These two well-written, unpretentious and engaging books address a central question for those interested in parliamentary democracy: who should represent us? Is the best representative someone just like ourselves, or someone who knows how ‘the system’ works and can manipulate it in our interest? Should it be someone from the party in power? Should it be someone wise and experienced, or young and vigorous? Should it be a woman, to represent the largest proportion of the electorate?

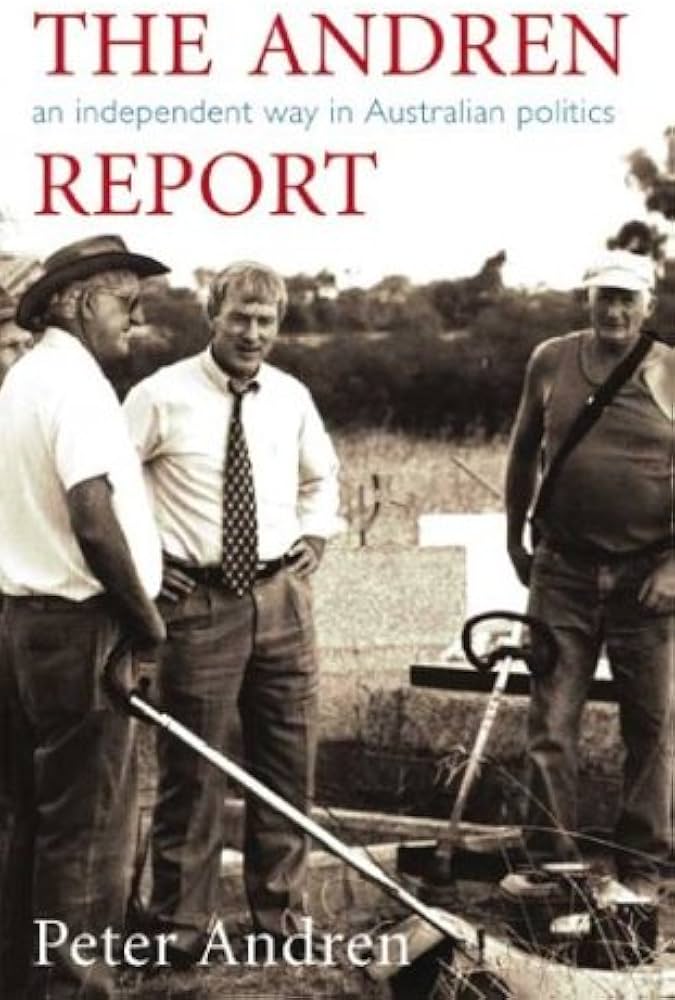

- Book 1 Title: The Andren Report

- Book 1 Subtitle: An independent way into Australian politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $30 pb, 303 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

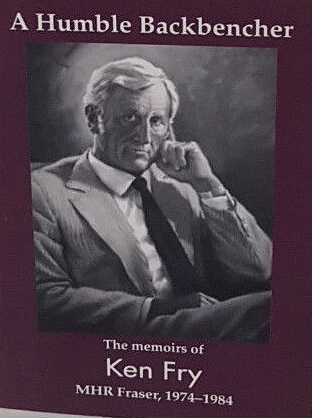

- Book 2 Title: A Humble Backbencher

- Book 2 Subtitle: The memoirs of Kenneth Lionel Fry

- Book 2 Biblio: Ginninderra Press, $25 pb, 166 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Fry was the President of the ACT branch of the ALP, and made his way into parliament in 1974 through the safe Labor seat of Fraser (ACT). His hardest battle occurred in the party’s preselection, where he had to defeat both the late Peter Wilenski and Susan Ryan. Since Wilenski had the support of the Labor machine and the incumbent prime minister, and Susan Ryan had the support of Labor’s feminists, prominent in Canberra, Fry’s win was no piece of cake. He remained a backbencher throughout his time in Canberra, and was the epitome of the hard-working, sane, sincere constituency representative.

Andren belonged to no party and ran as an Independent, winning the NSW country seat of Calare in 1996 from the ALP with National Party preferences, and retaining it in 1998 against the National candidate, this time with ALP preferences. In 2001 he won Calare in his own right, and appears to be as safe there as Fry was in Fraser. He, too, is a fine constituency representative, and he is well-known for speaking out on matters that he believes are important and on which his constituents are likely to have views different from his own. His views, in many respects, sound like those that Fry, sometime convenor of the left caucus in the ALP, would be voicing were he in Parliament now.

How does Andren survive? The answer has many elements. He is seen as his own man, beholden to no one. He makes it clear that he will call it as he sees it, and that he thinks it is his job to do so. He keeps his lines of communication open, so that none of his constituents is in any doubt about where he stands. On the face of it, he is polite and sensitive to those with whom he disagrees. Like any good local member, he is out and about all the time. He had excellent preparation for politics in serving as a television and radio journalist and editor for his region, so that he is widely known and widely appreciated.

All that is on the positive and personal side. Andren himself correctly points to some negative factors working against the established parties. Pauline Hanson’s electoral success a few years ago pointed to a profound disenchantment in the bush with all the major parties, emphasised more generally by the recent success of the Greens. Calare has been held by the Liberals, the Nationals and Labor in the last hundred years, and ought to be a decently safe non-Labor seat. But none of the major parties has learned how to make the local organisation of the party there resilient and self-confident, able to attract the next generation of the politically active and idealistic. All too often, ‘Sydney’ (meaning the central office of the party) makes the important decisions in preselection. Labor has shown no great interest in rural and regional matters, at the federal level at least, while the Nationals are widely seen as a small dog tagging along behind the metropolitan Liberal Party, unable to have any effect on issues such as the sale of Telstra, rural employment, health or education.

Andren had the intellectual training and experience to present these issues properly, and his twenty-five years in the central west have given him appropriate local status. He must also be a most personable man, because his success rests in part on his capacity to establish a large team of well-networked volunteers to run an effective electoral campaign against teams already in operation. Of course, there is nothing new in this. The Country Party did not exist in 1917, and its MPs in 1919 (federal) and 1920 (NSW) had mostly been soldiers in 1917. But their success in the polling booths was devastating. In some areas, Country Party candidates won eighty per cent of the votes. One of them, M.F. Bruxner, arrived at a village for a scheduled speech to find that the audience consisted of one man lounging under the hotel verandah. Bruxner spoke anyway, and walked over to join his audience. ‘Ar, you should get pretty well every vote here!’ was the comment. (He did.)

What underlies these electoral phenomena is a living and well-connected society whose members communicate on a daily basis and for whom politics is a pretty serious business. Ideas and opinions can move rapidly through this society, and gain the added weight of the local notables of all kinds who take up the cause. There really is no equivalent in large cities, where the population is much more mobile and electoral boundaries are simply streets or stormwater channels. Given that the Country Party achieved its power by mobilising rural society, it is instructive that its modern successor, the National Party, seems to have lost the plot.

Fry’s Canberra has something of the same quality, as it is a well-connected city of immigrants from other parts of Australia, most of whom share the view that ‘Australia’ (as opposed to Sydney, Melbourne, or wherever) is significant. Fry, too, said what he thought was important, and though he failed to win a place at the Labor banquet table, his constituents widely saw him as his own man. Without heat or bitterness, he points out that most MPs are going to be backbenchers, and they had better get used to the notion that there is an honour-able role there. After he left Parliament, he went back to university (he’d studied while serving as an MP) and completed two further degrees, the last a PhD, graduating when he was sixty-eight. There is life after Parliament!

Andren could certainly follow Ken Fry’s example. He could write a splendid PhD thesis on the superannuation entitlements of MPs and Senators, which he has criticised loudly and publicly, thereby attracting the united opposition of the rest of Parliament. Or he could develop yet another dissertation on the advantages of proportional representation, which, in his view, is the magic bullet needed to rid Australia of its degraded form of party politics. I don’t agree with him there, mostly on the ground that all electoral systems have costs as well as benefits. Proportional representation, for example, was thought to have ushered in the weak governments of 1930s France that allowed Hitler to grow powerful in neighbouring Germany.

I hope that Peter Andren has many years ahead of him in Parliament, and that his success prompts more good people to take the plunge, build a team and make another seat Independent. We could certainly do with more Independent MPs like Peter Andren – and more Labor MPs like Ken Fry.

Comments powered by CComment