- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Sport

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Silver and Gold

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1980, a nine-year-old Aboriginal girl in Darwin, Nova Peris, watched the Moscow Olympics on television and told her mum that she was going to be an Olympic athlete. Alone at home in Melbourne, Raelene Boyle was also watching those Games on the telly, bawling her eyes out and desperately trying to get drunk. Raelene was twenty-nine years old, a veteran of three Olympic Games, with three silver medals. She’d qualified to run in Moscow also, but by then frustration, confusion and disillusion had set in. For athletes, mid-life crises come much sooner than for most of us.

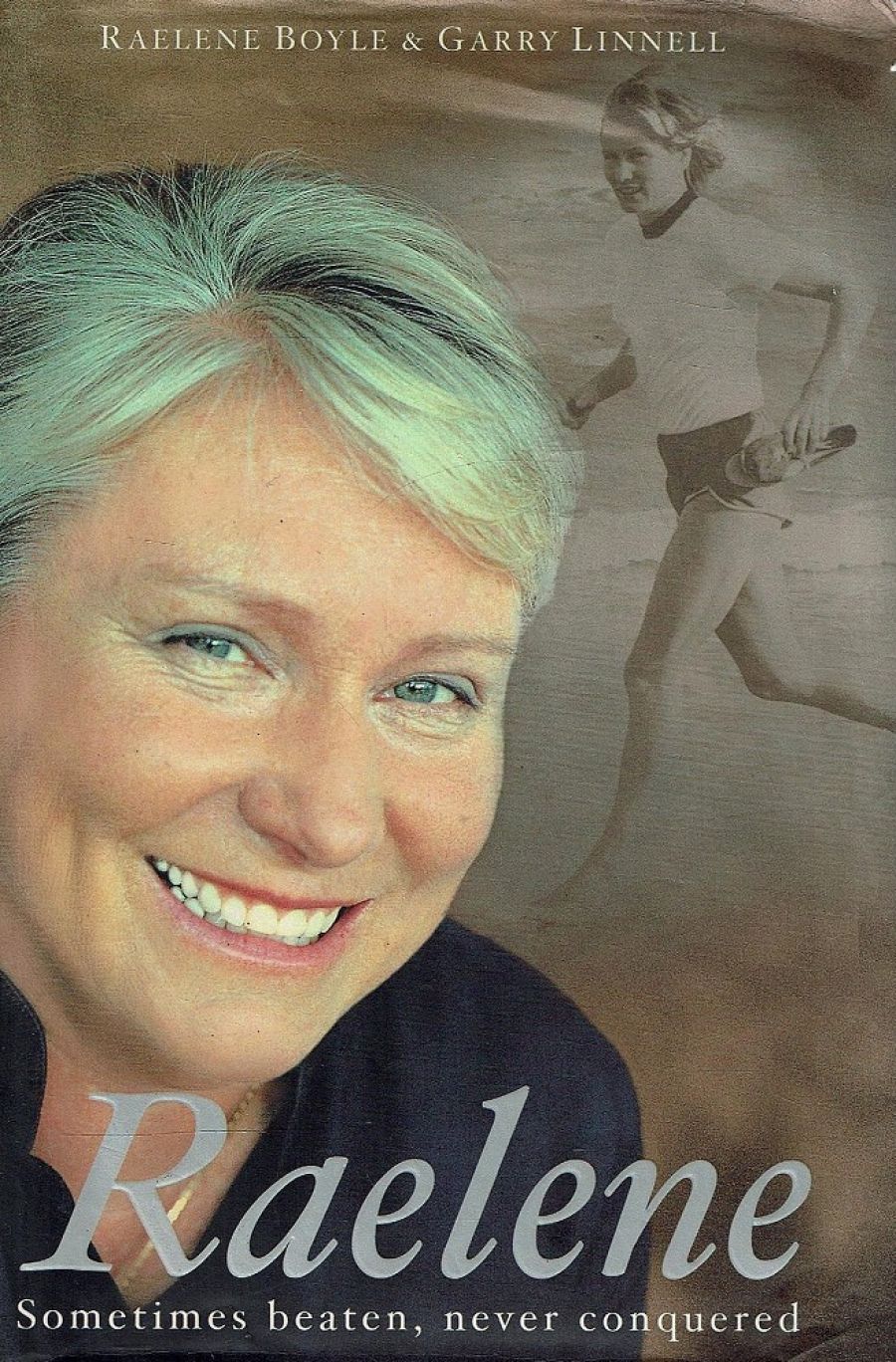

- Book 1 Title: Raelene

- Book 1 Subtitle: Sometimes beaten, never conquered

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $39.95 hb, 325 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

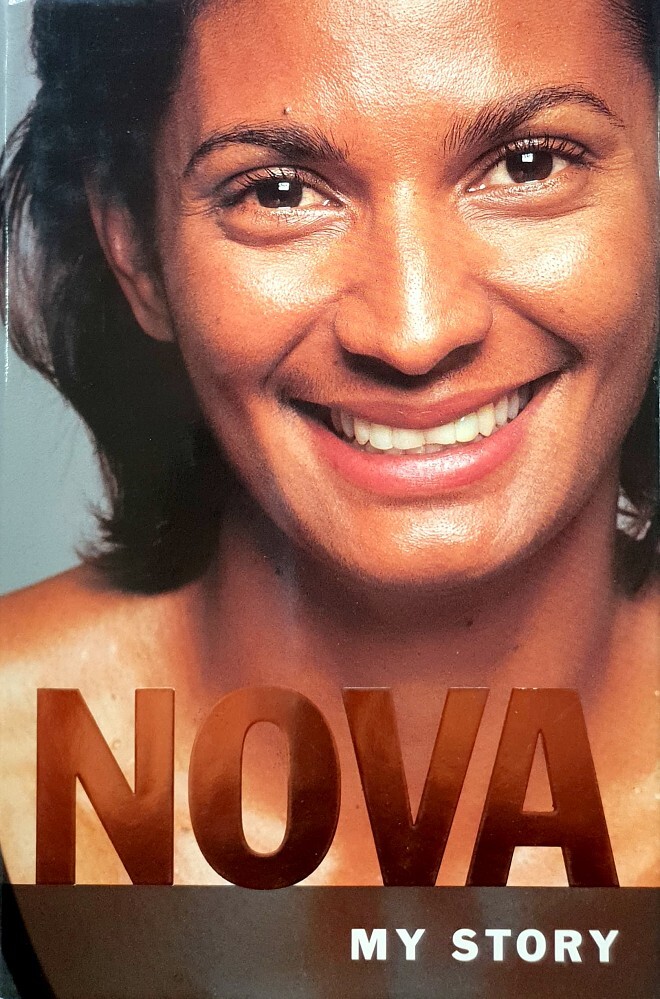

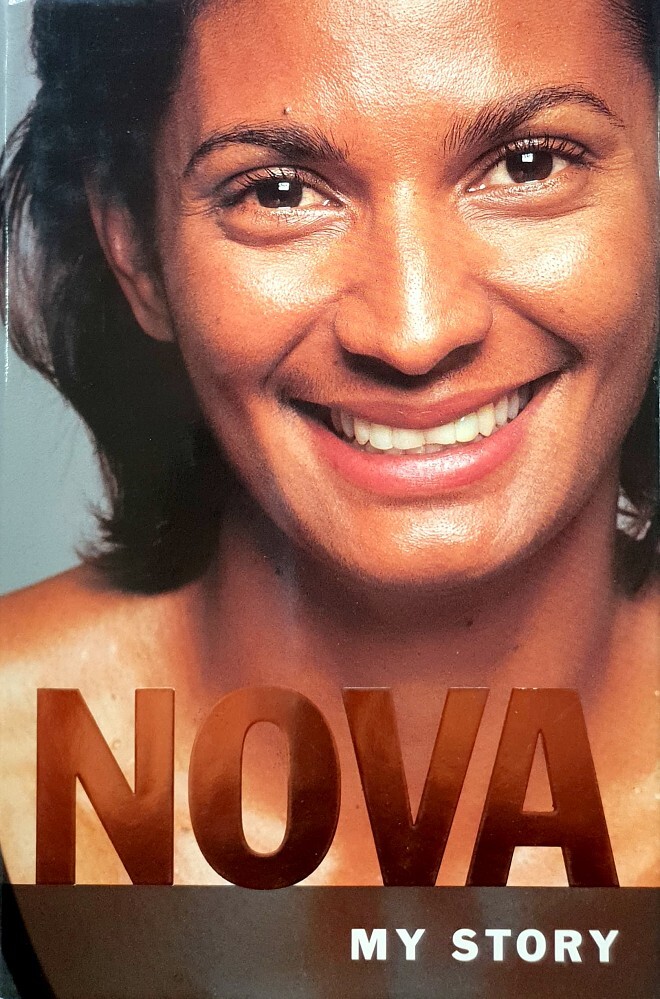

- Book 2 Title: Nova

- Book 2 Subtitle: My story

- Book 2 Biblio: ABC Books, $39.95 hb, 314 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

You couldn’t invent a better name for a sporty, working-class girl born in 1950s Australia than ‘Raelene Boyle’. Raelene grew up in the inner-Melbourne suburb of Coburg, under the shadow of Pentridge Prison. Her first experiences of sport are splendidly redolent of the era before kids’ sport meant being driven to a training clinic.

Some of the most seriously contested cricket matches staged in the western world took place outside our house in Sutherland Street … Sutherland Street also became my first training venue for sprinting. Whenever I was in a fight with the neighbourhood boys I was always the first to reach the front door of our home, leaving my frustrated pursuer well behind.

Sport is supposed to be the great meritocracy of our age, where natural ability plus hard work equals success. Athletes’ autobiographies invariably serve to confirm this: a none-too-privileged child with a talent and a dream triumphs against the odds. Raelene pretty much accords with this, but along the way it’s more interesting than most. That’s because, for all her talent and hard work, Boyle never quite reached the thing we’re always being told is the ultimate, the pinnacle, the apex and the zenith: Olympic gold. Hers was ‘a career dogged by bad luck and bad timing’, and that makes her story all the more intriguing. In 1968, as a raw seventeen-year-old, she unexpectedly won a silver medal in Mexico City, and was poised for greatness in international sprinting at a time when Australian track and field success had all but dried up. The following decade, though, turned out to be a troubled time in world sport, and those troubles had their impact on Raelene Boyle.

The Munich Olympic Games of 1972 are forever marked by the terrorist siege that killed seventeen people. They’re also remembered for East Germany’s sudden and suspicious leap to sporting success. Raelene was beaten by a chemically-enhanced East German sprinter two days after the massacre at the airport. ‘There was no place, it seemed, for a hopeless romantic in a sporting world as brutal and calculating as this one had turned out to be.’ The 1976 Montreal Games were another low-point in Olympic history. Sixteen African nations boycotted the Games over apartheid, and the host city was left bankrupt by the expense of staging the event. Raelene’s rotten luck continued. She was called twice for breaking out of the starting blocks and disqualified. Film footage later showed that in fact she hadn’t broken the first time, but by then the race had been run and won without her. As Australia’s greatest all-time sporting fluke, Steven Bradbury, could tell you, luck is the X factor in the meritocracy of sport. Which also probably explains why so many sportspeople are deeply superstitious at the same time as espousing the ethic of hard work.

Raelene’s willingness to admit to vulnerability and uncertainty is most affecting. Where the onlooker sees a tragedy of circumstance, she saw a tragedy of character. ‘I thought I was soft. My character, I believed, was suspect under pressure.’ In the superhuman world of high-performance sport, a bit of real human frailty and doubt is a blessed relief to read.

It is in its particulars that Nova Peris’s little-girl-with-a-dream story is of interest. Deciding to try to be an Olympic athlete when you’re an Aboriginal teenage unmarried mother invites doubters and naysayers. In 1992 Nova packed up her car and baby daughter and drove from Darwin to Perth, where the national hockey programme is based. Mother and child slept on a single mattress in the corner of someone else’s rented unit. With the energy that’s inspired by self-belief, Nova got on with holding down a job, raising a toddler on her own, and training to try to make the national squad. Nova’s good fortune was that her move on the big time coincided with Ric Charlesworth becoming coach of the Hockeyroos. Nova gives a revealing inside picture of Charlesworth’s approach to sport and success. In the lead-up to the Atlanta Olympics in 1996, each member of the team was required to commit to a ten-point plan. There’s all the usual stuff about determination and dedication, but number eight in Charlesworth’s creed is a more surprising inclusion. ‘I will be the best I can be by being tolerant of differences in others and respecting them for who they are and what they have to offer.’ For a young woman who had to cop a fair bit of discrimination within and beyond sport, this attitude held deep significance and affirmation.

After becoming the first Aborigine to win an Olympic gold medal in Atlanta, with the mighty Hockeyroos, and with a huge chance of repeating that feat in Sydney in 2000, Nova decided to remake herself as a runner. Most of us, if we’re lucky, are good at one thing. In her teenage years in Darwin, Nova had made representative teams in six different sports, but being multi-talented produces the dilemma of choice over destiny. Nova made the switch, sprinted to a gold medal at the Commonwealth Games in 1998 and then made it through to semi-final level at the Sydney Olympics.

Nova, having represented Australia at top level in hockey and in athletics, is unusually qualified to compare the two sports firsthand. Of course, there are considerable inherent differences between a team sport and a mostly individual sport, but Nova describes a big gulf in attitudes and approaches within these sports that hints at why Australia’s international performance in track and field has been generally poor for so many years.

As with most autobiographies by athletes, Nova and Raelene are both written with the help of a sports journalist. In each case, a different kind of co-author might have provoked the subject into richer and more articulate insights. Nova goes on about being a ‘spiritual person’, without dwelling on what this means or how this spirituality has informed her life and approach to sport. Raelene mentions that her love of running was always about more than the dash from start to finish line. ‘To move beautifully as well as running fast is a sort of perfection to me.’ Unfortunately, she doesn’t elaborate on the aesthetic appeal of running, or even whether this is an unusual attitude for a sprinter to have. What does moving beautifully as a runner feel like from the inside? Is this ultimately more meaningful than winning medals?

Although Nova and Raelene read at times like transcripts from This Is Your Life, both are heartfelt stories from admirable women. Each has gone on to become an advocate for causes beyond sport that have meaning for them. For Nova, it’s indigenous issues and a Treaty; for Raelene, it’s cancer awareness (since her running days, she’s copped both breast and ovarian cancer). They pursue these causes with the same sincerity with which they approached their sport, and write about them with the same passion.

Comments powered by CComment