- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Quite a Year

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Those who call 1942 ‘Australia’s most perilous year’ are not guilty of over-dramatisation. It was, after all, the year when Japan’s aircraft blasted Darwin off the map; when her submarines entered Sydney Harbour, sank a ship and shelled the shoreline; when air raids were happening around Townsville, and Australian ships were being sunk off our coast. It was the year when our best military and air forces were engaged far away in Africa and Europe; when ‘impregnable’ Singapore fell, ending long-held illusions of an Australia safe beneath the imperial British umbrella. It was the year in which a proud Australian fighting force began years of cruel captivity. It was the year John Curtin, acknowledging a brute fact of life, placed Australia’s forces under US command; the year we managed (with massive US help) to hang on by a whisker in New Guinea, ‘the nearest’ – in the words of the Duke of Wellington – ‘the nearest run thing you ever saw in your life’.

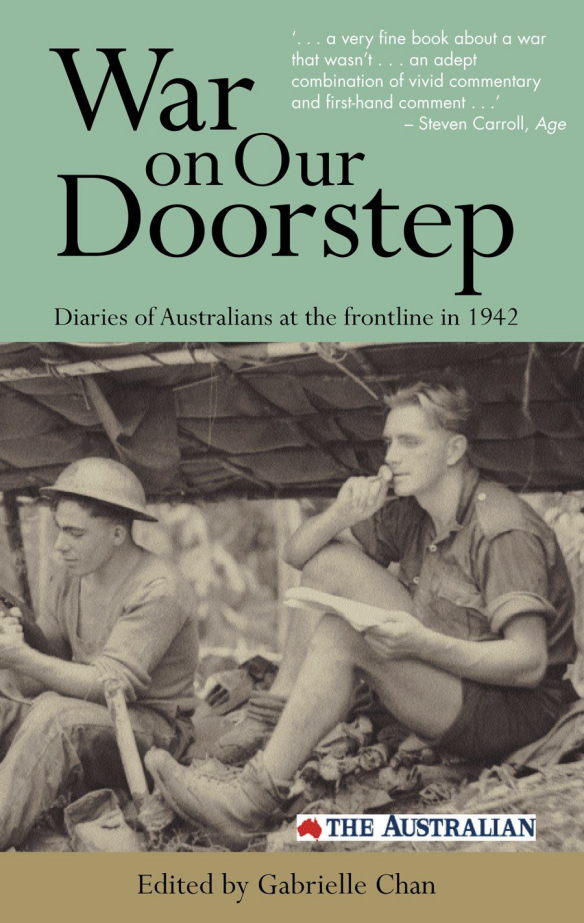

- Book 1 Title: War On Our Doorstep

- Book 1 Subtitle: Diaries Of Australians At The Frontline In 1942

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant, $29.95 pb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

With hindsight’s faultless vision, we now know that Japan never intended to invade or occupy Australia, a fact which today leads some people to believe that all the panic in 1942 was a little overdone. The question of invasion as against non-invasion hardly matters. The real point is that, if the Japanese had taken Port Moresby, with its superb harbour and limitless level sites for airfields, Australia would have been isolated in impotence while the war lasted, and a mere poodle of the victor thereafter.

So it was with sound reason that The Australian newspaper chose 2002 – the sixtieth anniversary of that hinge of national fate – to select extracts from diaries kept at the time. Most of them are of Australian men in one of the three armed services, though the indomitable Sister Vivian Bullwinkel (sole survivor of a group of Australian army nurses murdered in cold blood by the Japanese) has her eloquent say.

When these diary extracts first appeared, one at a time in each day’s paper, I found them disappointing. They were so ‘bitty’, lacking background and context. Such tiny instalments at twenty-four-hour intervals provided little impact and atmosphere. Their presentation here, in a crisp, inviting paperback, lends a wholly different aspect. Under Gabrielle Chan’s capable editorial hand, with tactful passages of introduction and helpful brief notes, the diaries gather coherence and force: indeed, some entries kick like a mule.

There are surprises. Who would have expected to find the artist Donald Friend in such company, especially those old enough to recall Friend’s outrageously self-exaggerated persona as a prancing queer? The sneers of this intellectual snob are powerfully emetic, as he denigrates better men – soldiers going off to fight and bleed. His diary was written from his safe army camp in the Riverina. Yet strangely, in a later entry, Friend records a reflection that spoke very powerfully to me: though we must all be prepared to kill in a just cause, it nevertheless remains immoral to hate. This I understood. When I was being evacuated from New Guinea after the battle of Kaiapit in September 1943, we passed a Japanese prisoner lying wounded on a stretcher laid beside the track. Our glances met. So far from hate, I felt for him only pity in his present terrible state. But I would have killed him.

Nothing could be further from Friend’s highly coloured campery than the cool matter-of-factness of Martin Clemens, lone coast watcher on that small Solomons island of which US Admiral Halsey said: ‘the coast watchers saved Guadalcanal, and Guadalcanal saved the Pacific.’ The heroic and costly battles by which the US Marines won this island all hung, for a time, on the thread of one man’s nerve. Clemens – he must be nearly ninety – lives on today in Toorak, dapper as ever.

It is pleasing that Chan mentions the Australian raid on Salamaua in June of that crucial year, because it was the sole offensive operation undertaken then in the whole of General MacArthur’s vast south-west Pacific theatre. In a classic guerrilla operation, commandos of the 2/5 Independent Company entered the town at night, slaughtered about one hundred enemy troops, and left the enemy base a smoking shambles. Our losses: a couple of men wounded. A pity that there is no diary entry here from one of the men who did the job.

For spookiness, read the diaries of the Australian navy divers sent down to find the Japanese submarines sunk on the seabed of Sydney Harbour. For horror, read of the Australian hospital deliberately bombed by the Japanese in November. Twenty-two men were killed, including two surgeons, and fifty men already wounded were wounded again. One patient called ‘Help me!’ with both feet blown off, and ‘his calf muscles hanging down in strips’. And you can read the precise, dry observations of ‘Doc’ Vernon. The job of this old New Guinea hand and World War I veteran was to care for the native carriers on the Kokoda Track. When the fighting started, this great soul and fine soldier discovered that he must treat Australians, too. So appalling was the state of Australia’s military readiness that the 39th Battalion had been flung into battle without a medical officer.

And throughout the volume there is laughter – perhaps the sanest of humanity’s reactions to even the worst of its disasters.

Of this excellent book, a striking general impression remains. All the words are those of ordinary Australians who would, for the most part, have gone to school in the 1920s and 1930s. How well they wrote! What good, unfussy English! Would the class of 2002, for all their extra years of school, and the ‘advantages’ of modern education – would they be able to express themselves so well?

Comments powered by CComment