- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Defying the Uncivil

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

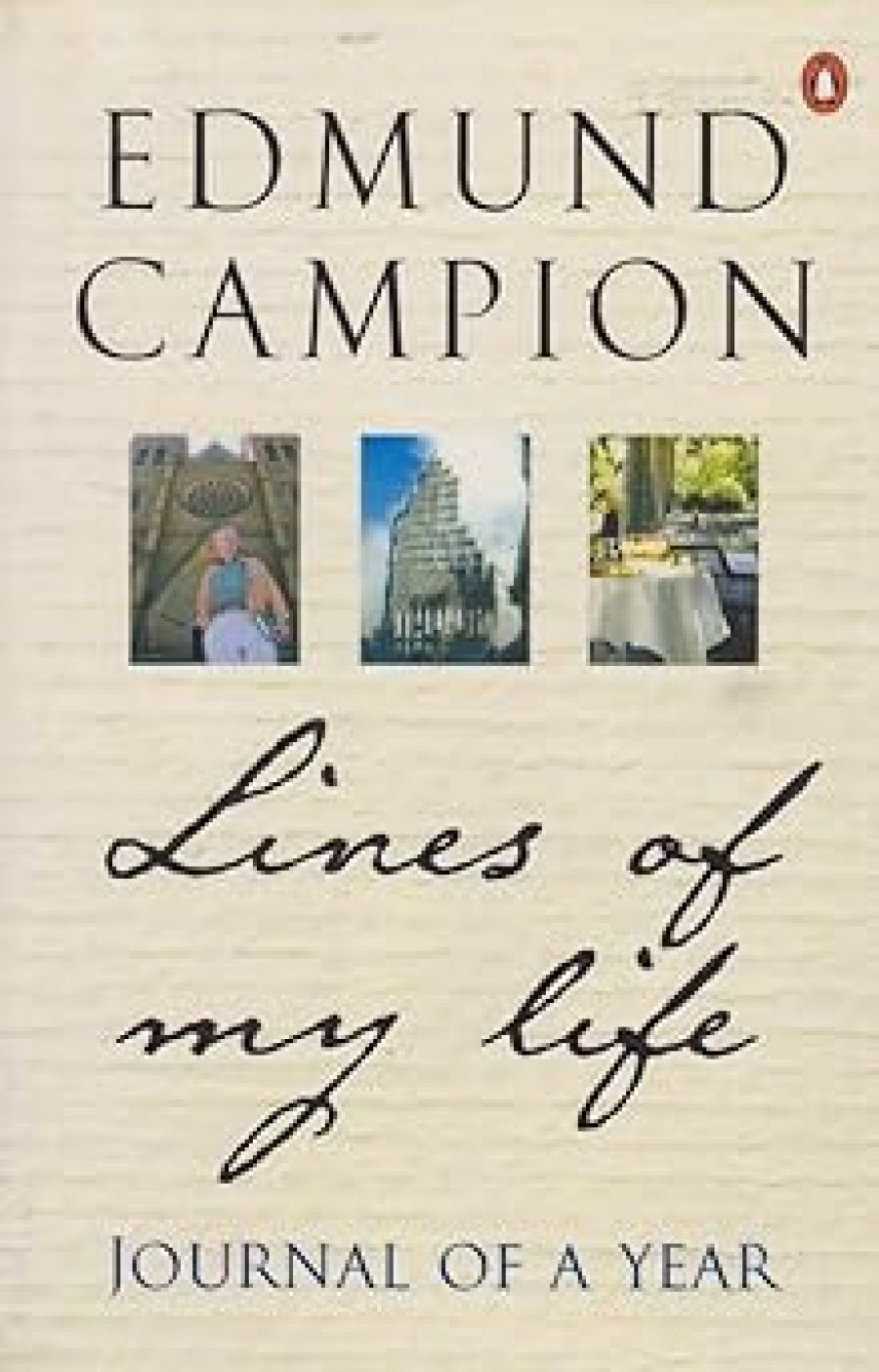

Edmund Campion’s latest book, Lines of My Life, is an elegant hybrid, part meditation, part gossip (of edifying kinds), part political testament. Its genial tone is suggested by the source of the title, which comes from Psalm 16: ‘the lines of my life have run in pleasant places’. Not that this is at all a self-satisfied book. Campion begins his ‘Journal of a Year’ in New York in September 2001. He had gone there to conduct research on Thomas Merton, an American monk and writer. This took him to the great public and university libraries of the city. In one of the moments when Campion pauses to praise, he says that ‘libraries are our richest cultural asset, their custodians singular servants of our intellectual lives’.

- Book 1 Title: Lines of my life

- Book 1 Subtitle: Journal of a year

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $22.95 pb, 269 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

But he had come at an unpropitious time: ‘less than a fortnight later, the acrid smell had gone from the air’, however the signs of mourning, shock and bewilderment in the aftermath of the September 11 terrorist attacks were to be seen everywhere. Perhaps out of a desire not to trespass on the sorrows of others, Campion does not dwell too long on the tragedy. He does say that ‘the past few weeks in NYC will prove a vast research field for anyone interested in how people handle grief’. Then his attention turns elsewhere: to the Columbus Day Parade, to Peter Carey, possessed of a diffidence ‘as if he were uncertain about his great talent and the authority it gave him’. Once Campion is stirred to anger by an historian’s virulent attack on ‘modernity’. Campion judges acerbically: ‘So this is the rollback from Vatican II … Taliban Catholicism.’

By October he is comfortably back in Sydney, with a brilliant Patrick White joke to open proceedings. Then there is an anecdote about an odious owner-builder who is renovating a terrace near Campion’s house in Paddington. When the jackhammer comes out on Saturday morning, the citizens rally, the police turn up, the owner-builder’s bluff is called. It’s a minor and temporary win, but Campion concludes from it that ‘the uncivil of this world must be resisted’.

If Campion is exercised by the present state of the Catholic Church, he also takes a more inclusive interest in the condition of the whole Christian community. He addresses a subject whose name is seldom spoken now, when – only a few decades ago – it had great disruptive power. The word is sectarianism. Writing in praise of the new Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, Campion argues that, while the old divisions between Catholics and Protestants in Australia have diminished (five of the most recent leaders of the New South Wales Liberal Party have been Catholics, he notes with some astonishment), those between pluralists and fundamentalists of either denomination have bitterly deepened.

He recalls the faux fax in which former priest Paul Collins supposedly and abjectly recanted his previous attacks on the establishment of the Catholic Church. It was a cruel, meditated hoax of which Campion comments that ‘Collins could have been destroyed by some Catholic conservative acting in the name of God and Pope John Paul II’. More generally, he laments the damage to the entire Catholic culture in Australia, sadly describing ‘the gap in people’s sense of Catholic selfhood, the hole in their hearts, the devotional vacuum they were experiencing since much of Catholic popular culture had evaporated after Vatican II’. These are not wants that he can, with any confidence, see being met.

Usually, Campion’s contacts in the world fill him with hope. He writes of Tom Keneally appreciatively: ‘what a great preacher was lost to the church when Tom left the seminary.’ (Happily for most of us, we got the novelist instead.) The reasons for Keneally’s decision would not have surprised Campion, as he remembers his agonised struggle ‘to stay alive in the faith through the years of seminary hunger’. Life in a wider society, that of Sydney in particular, has nourished Campion’s perceptions, and his charity. He writes of Patricia Rolfe, long-time literary editor of the Bulletin and a great supporter of Donald Horne in the early years of his editorship. In return, Horne described Rolfe admiringly as resembling a ‘worldly Renaissance prioress’. It is she who gives Campion an anecdote to savour: the sight of Don Anderson, Dick Hall and Frank Moorhouse at lunch, surrounding a single bottle of mineral water.

As befits one who speaks of ‘old timers like myself’, suffers from diabetes and so knows that ‘old age is not for sissies’, Campion is often at the funerals of his friends. None of these seems to have been a doleful occasion.(Since the book was published, Hall has joined the lost ones.) Other months in this year find Campion wondering where the Centennial Park rabbits have gone, watching Test cricket at the SCG and travelling to the Treasures Exhibition at the National Library of Australia. This wonderful array of materials from the great libraries of the world was so popular that it was opened for twenty-four hours a day. Campion took from it a consolation typical of him: ‘everyone who went to the Canberra exhibition came away with a heightened sense of the values that we call civilised.’

That is the sense that Lines of My Life imparts as well. Urbane and affable, Campion is still alert to how institutional cruelties and prejudices can deform those who practise them, and of how that practice damages the chances of civilised life. Such a life he has found in Australia – and in the US. He is back there in September 2002, although he writes on the day of another departure for home. To express his love for New York, Campion gives the last words of his book in gratitude to the city’s most famous poet, Walt Whitman, who saluted a ‘City of hurried and sparkling waters! City of spires and masts! / City nested in bays! my city!’

Comments powered by CComment