- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

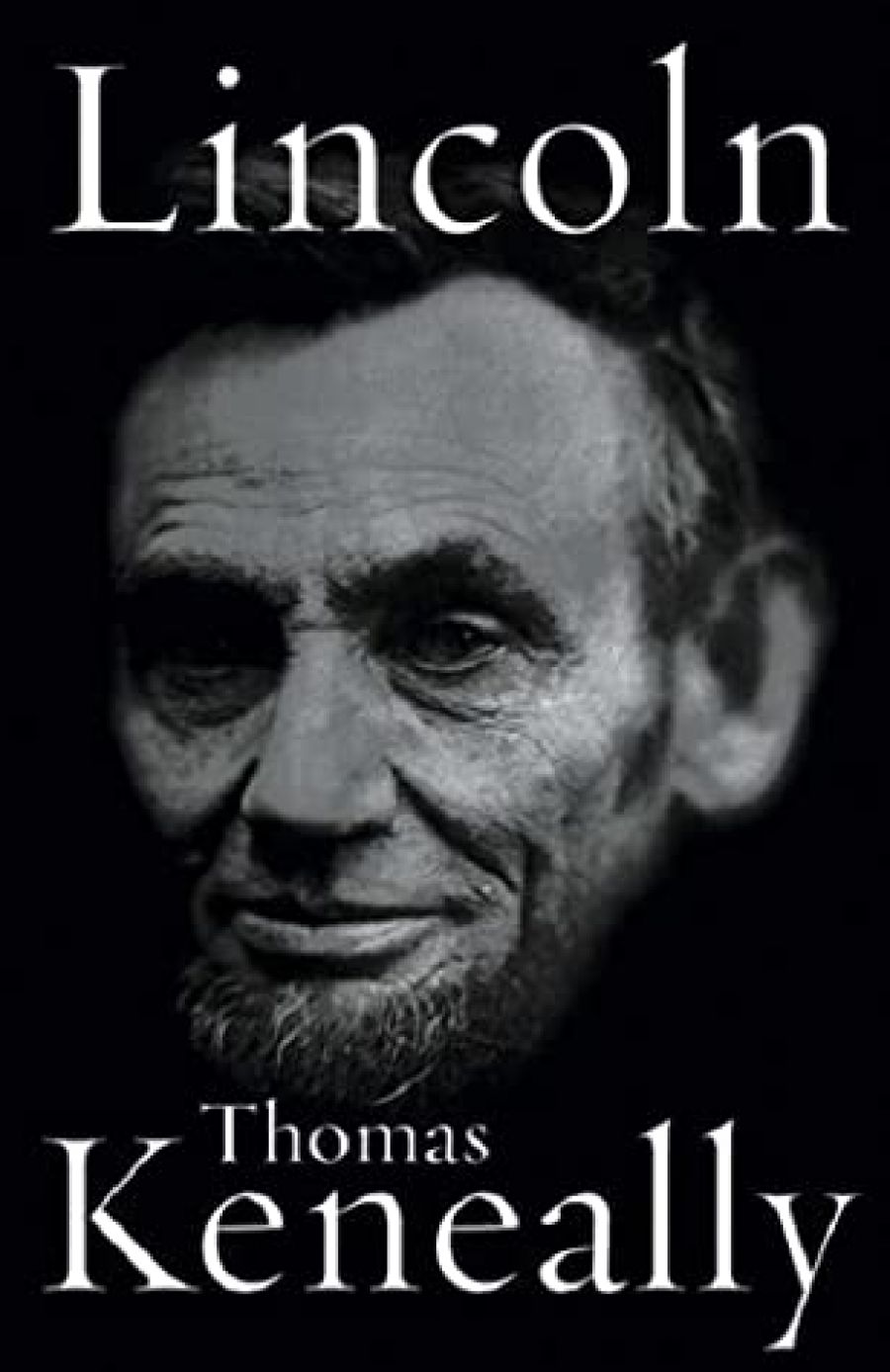

Weidenfeld & Nicolson were both wise and fortunate in their choice of Thomas Keneally to write a study of Abraham Lincoln for their Lives series. He in turn gifted them, and us, with a story that listens closely to Lincoln’s words and sees some shape in the internal and external demons that so often troubled his life. Keneally’s narrative moves quietly alongside the Illinois rail-splitter as Lincoln transforms himself from local small-time politician to President of the USA.

- Book 1 Title: Lincoln

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $35 hb, 202 pp

There are, of course, reasons for assuming a mournful voice in writing about Lincoln. Mid-nineteenth-century midwestern voices have a fatalistic tone – folks remembering Lincoln, that of his Illinois law partner William Herndon, the speech of Lincoln himself. They are flat like the hard unpromising prairies, gloomy like the hymn-singing of isolated farm families. Moreover, Lincoln was given to persistent melancholia. His wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, was unstable; two children died young. In place of a civil war, Lincoln wanted peace. He said of the Union that ‘a house divided against itself cannot stand’. Yet he did not know how to keep the North and South together. And there was Lincoln’s face. ‘Angular and unconsolable,’ writes Keneally of a portrait painted in the war’s final months. Then the hatred of the secessionists and the assassination. The mournful funeral train from Washington to Illinois. The tearful verses of Walt Whitman.

Keneally’s prose takes on some of the soulful prairie language and tragic sense that the life of Lincoln necessarily evokes. We hear of midwestern predestination as ‘the tenet of the preaching houses of the hinterland’ and young Lincoln as sometimes ‘odd-seeming’. Keneally puts together the words ‘dark and edgy amusement’ to describe Lincoln’s response to the growing public image of himself as a metaphor for the virtuous and democratic Jeffersonian farmer.

But Keneally’s sensitivity to language is always judiciously deployed. He can establish moments of continuity with the tonality of the nineteenth-century voices, but he can also work within his own expressive narrative style. Keneally’s Lincoln is a troubled but ambitious man. He seizes career opportunities and courts politically useful friends. He teaches himself to read public opinion with as calculated an eye as he learns to read law. He writes hundreds of (signed and unsigned) editorials and gives – in their hundreds, too – speeches meant to stir admiration.

In Sangamon County, Illinois, the issues an office-holder had to consider in the 1840s were mostly local. The farmers were concerned about a canal, a county debt, the introduction of a bank. But none were ‘yokels’, and they were also concerned about national issues. So, by the 1850s, Lincoln was taking a stand on the matter of southern slavery, particularly its extension into the country’s new states and territories. Keneally’s position is that Lincoln opposed slavery on principle. He did not, however, think a slave equal to a white man. Nor did he support the abolition of slavery in the present slave states unless the slave-owners agreed to compensated emancipation.

Lincoln began to speak publicly about the threatening spread of slavery. He denounced the proposed compromise called ‘popular sovereignty’. By this plan, people settling in a new state might write a constitution according to whether a majority had voted for slavery or voted it down. No, said Lincoln. The western lands are there for independent farmers, not slaveholders and their human chattel.

As a candidate of the newly formed Republican Party, Lincoln won the presidency in l860. The victory was ominous personally, and for the nation. He won only because the opposition Democrats had split, North and South, over slavery. Lincoln left Illinois for Washington in December. (Here, Lincoln hagiographers usually note that he left this message for Herndon: ‘If I live, I’m coming back sometime, and then we’ll go right on practising law as if nothing had ever happened.’)

The events of the wartime presidency allow Keneally to catch, in some of Lincoln’s performance, attributes on which we have seen him reflecting since the book’s first chapters. He looked for early signs of Lincoln’s oratorical eloquence and thought he’d found them in 1832 when Lincoln was twenty-three. Concluding one campaign speech, the aspiring politician said, ‘If elected, I will be thankful. If beaten, I can do as I have been doing, work for a living.’ Here was a ‘western pithiness and lack of pretence. He spoke in an idiom to which the novels of Mark Twain would give an international currency.’

After 1860 Lincoln was sculpting that eloquence to a fine art. He was doing so at the cemetery in Gettysburg and on the inauguration platform set before the Capitol Building in 1861 and 1865. He worked on speeches to Union regiments returning on leave from the war and to whom he was already ‘Father Abraham’. One of the reader’s joys in reading Lincoln is in encountering those astonishing passages and attending to Keneally’s passion for deciphering them.

Lincoln had made himself a passionate speaker because he was a passionate politician. Political oratory was ‘somewhere between an art form, a sport and a drug’. And the political game was one that he played hard, even to his last days in the White House.

In 1850, after serving a term in Washington as a congressman, Lincoln was at home and wrote to a friend: ‘I am reading books again, The Iliad and Odyssey. You ought to read it. He has a grip and knows how to tell a story.’ One has to wonder whether Lincoln shuddered at Homer’s fierce metaphor for armed conflict as ‘the wide-open mouth of bitter war’. The Civil War was to be the most bitter event in US history. Predicted to last six weeks – the South was expected to be easily defeated – it went on into a savage fifth year. Lincoln pursued the conflict in order to save the Union and, in the final months, to free the slaves. Yet the tensions between racism and anti-slavery that Keneally found existing often ‘in the same soul’ continued to exist in the soul of the nation until well after the war.

Keneally chooses not to follow this story. He ends with Lincoln fallen victim to John Wilkes Booth’s single pistol shot. He became, as Keneally writes, ‘the bloodied nation incarnate’.

Comments powered by CComment