- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

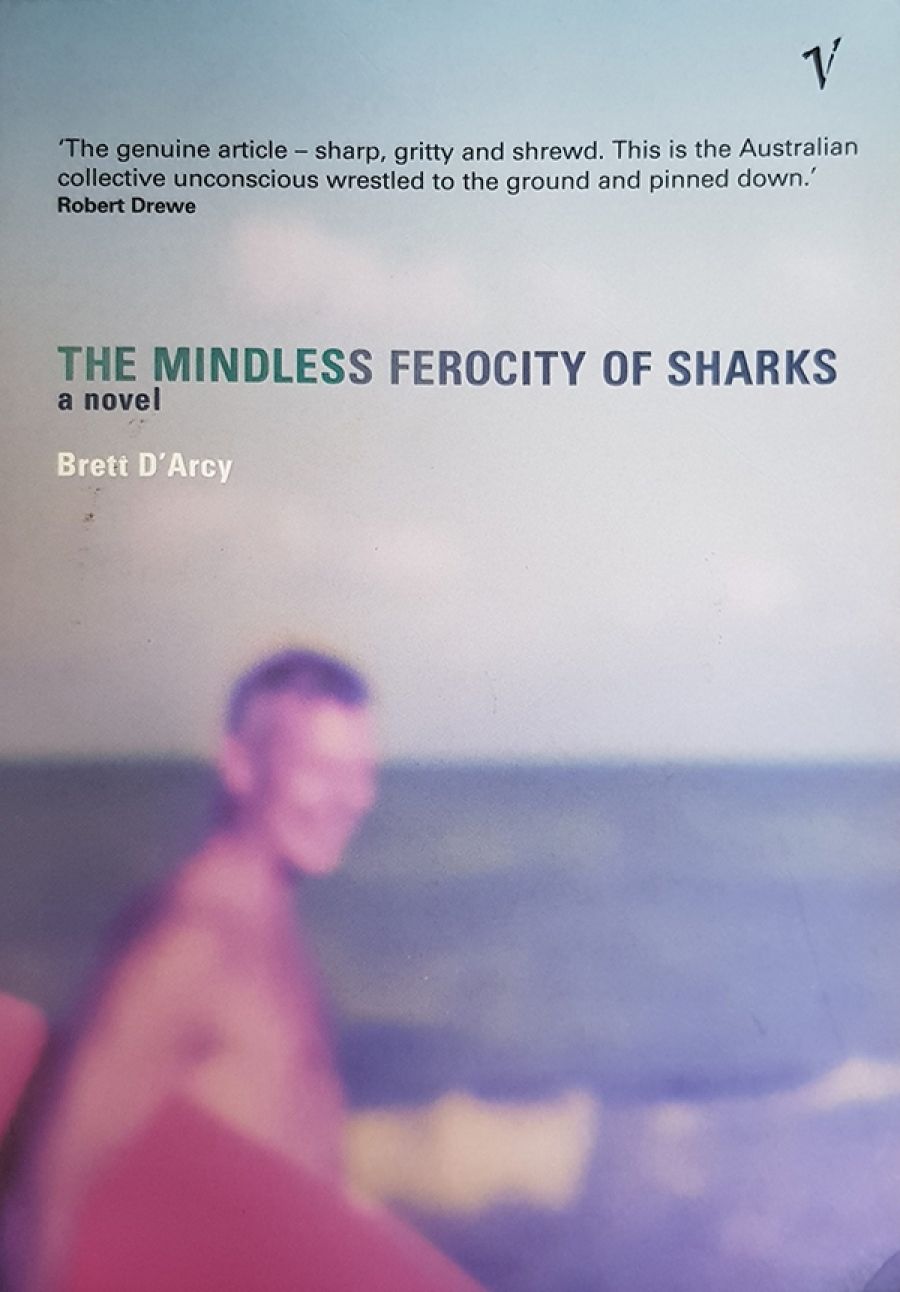

Brett D’Arcy’s novel, arrestingly titled The Mindless Ferocity of Sharks, is one of the most unusual and accomplished to be published in Australia for years. The setting is a decaying town called the Bay on the coast of Western Australia, south of Perth. Its abattoir and tanneries have long since closed. The locals are sufficiently hostile to have fended off development – so far. They endure the summer invasion of the ‘townies’ who come for the great surfing. During the rest of the year, they enjoy it without interruption.

- Book 1 Title: The Mindless Ferocity of Sharks

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $22.95 pb, 300 pp

The management of Floaty-boy’s narration is the technical triumph of the novel. The events around him have the heightened and disconnected qualities of a dream. The details of his physical environment are nonetheless sharply observed. It is as though we are dropped into a hyper-naturalistic stage set. The parents’ home and shed are full of the junk and surfing collectables in which the Old Man trades. We are introduced, in puzzlement, to a world of mals, hunkas, tooth-pick guns and even the legendary ‘black Dora’. There is no glossary. We accept D’Arcy’s terms as we venture into the places that he so freshly and disconcertingly imagines.

Through Floaty-boy’s consciousness, we gain a sense of the strains and compromises in his family life. Adelaide has a troubled past (darkly but inconclusively hinted at a couple of times), has been to university, works part-time as a journalist, occasionally rages at her parasitic menfolk, but is weakened by desire for her husband. As Floaty-boy grimly reflects, all he had to look forward to was ‘the sound of fighting and fucking all night’. By day, the Old Man runs desperate scams, as if trying to prolong a delinquent, sunny adolescence. D’Arcy makes him infuriating, engaging, plausible.

The Old Man – Ulysses as ageing surfer – enjoys absenting himself from wife and home. With Floaty-boy, he searches for his runaway son Eddie: south to Upland, where the dune-surfing Sand Punks live; north to Perth and to Rottnest Island, of which he reflects: ‘that place has a tragic history … Reminds me of fuckin’ Tasmania.’ Not for the first time, we think of D’Arcy’s book as Tim Winton on speed. Yet there is an original note throughout. D’Arcy is measured in his handling of fractious and untidy material.

Consider the vernacular ease of his writing. This of the family pet: ‘Brick is more like the ghost of a previous tenant’s dog.’ This of the baby: ‘Sal is fussed over and passed around like a smoke.’ And then this chilling reflection from Floaty-boy, on being dragged deep under the sea by a wave: ‘the details of Down Below came rushing back at the boy – the perfect darkness, the secrets, the treachery – like nothing so much as the inside of his head.’ D’Arcy can also pull us up by writing tersely. Floaty-boy tells his mother that the worst thing about his medication is: ‘It stops me laughing.’ And, in a moment of empathy for a father whose life is dedicated to masking his own vulnerability: ‘It can’t be easy being the Old Man. The onus is always on him.’

Venturing into the sea, surfing heedlessly at night, Floaty-boy temporarily frees himself of the aggravations of his family. Yet he also subjects himself to terror. He thinks always of ‘the mindless ferocity of sharks’, one of which nearly killed the Crony Gav, who has remained somewhat apart from his mates ever since. And there are sharks in the Bay. Floaty-boy glimpses ‘a dark broiling and a matt black flank’ as a shark feeds. The novel’s climax brings on a shark, a bronze whaler, but to no effect that has been telegraphed or could easily have been anticipated.

It took so long for Australian novelists to take to the beach and sea. One thinks of Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Intimate Strangers (1937), also set on the coast of Western Australia, and Watson’s Bay in Christina Stead’s For Love Alone (1944). Then one has to jump to Winton and to Robert Drewe’s The Bodysurfers (1983). Aptly, there is an encomium from Drewe on the front cover of D’Arcy’s book. Whether or not it wrestles ‘the Australian collective unconsciousness’ to the ground, as Drewe reckons, The Mindless Ferocity of Sharks is an acute depiction of an insecure hedonism that is the mask of Australian nihilism, and of the desire to escape from any obligation save the self-imposed. D’Arcy’s achievement is to plumb such despair, while rendering as well the black jesting that attends it.

Comments powered by CComment