- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

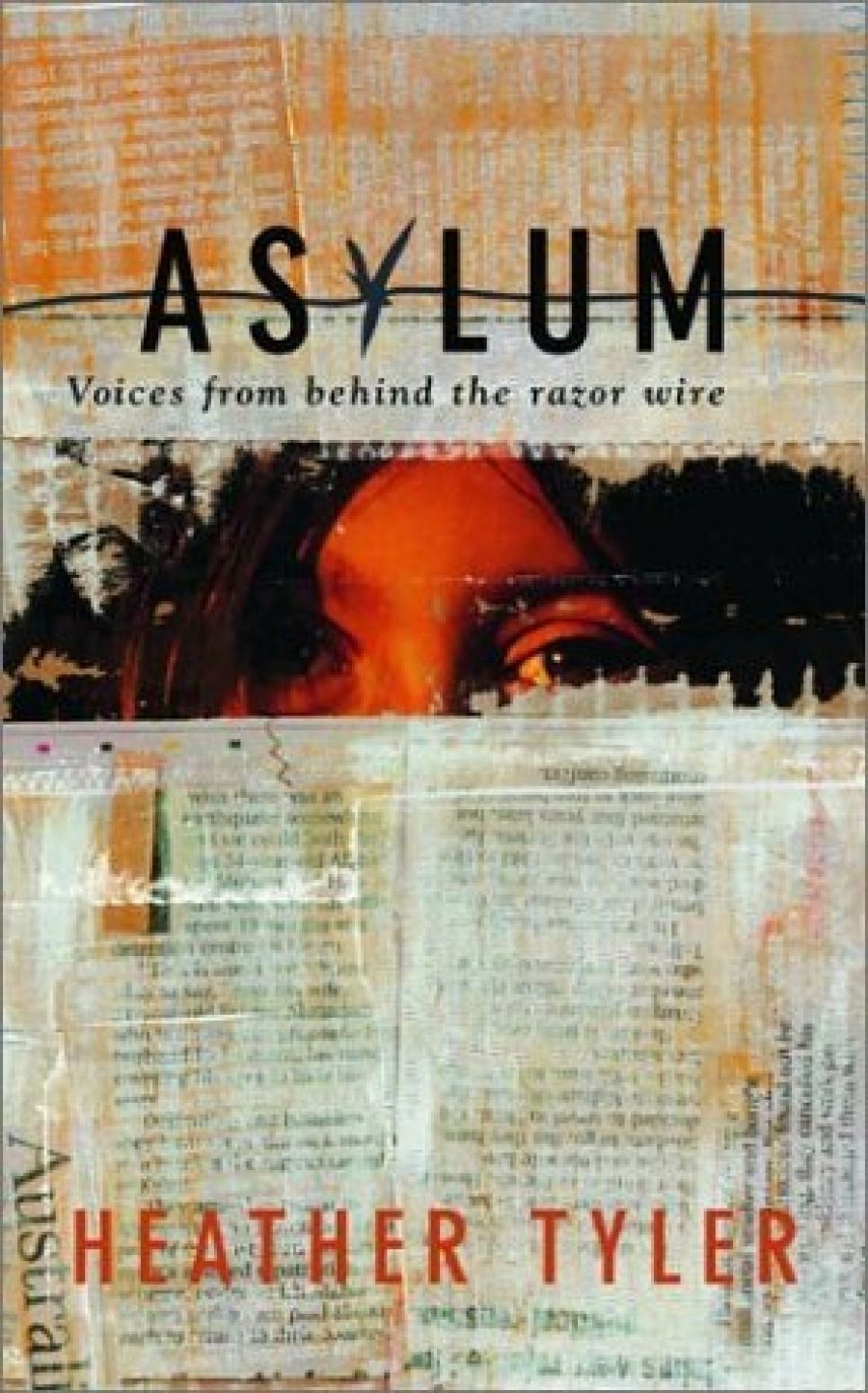

The concluding sections are equally well structured. The penultimate chapter, ‘Crisis, What Crisis?’, leads us away from the personal stories into a disturbing summary of the development and key events in the emergence of the Australian detention regime. The final chapter turns to the people and some of the grassroots organisations that try to help detainees; and to the role of the media.

This is a compelling book with some flaws, most of them minor. One must be mentioned. ‘Everything but the Truth’, in which Heather Tyler tries to present an explanation as to why Majeed lies about his experiences, is the least successful chapter. I am always uncomfortable when specific encounters and individual anecdotes are used as emblematic of an entire culture. Many people would find the assumptions in the quotation from journalist Thomas Cromwell offensive. The implication that in our political system we don’t lie, and in theirs they do, is also unintended and irrelevant. People who have been tortured or feel shame over what they have experienced often lie or suppress key facts. When people fear for their future, and do not know whether they can trust authority figures, they will lie; but to contextualise all this in an unscholarly judgment about cultural difference, backed up by a Western journalist’s anecdotes, does not advance this book or the salient point that Tyler is making. The most important point, with respect to Majeed’s lies, has been made elsewhere, most recently I believe by psychologist Lyn Bender: refugees’ silences, what they will not say, are perhaps the most important issues for a tribunal assessing their refugee status to uncover. Tyler’s handling of the story of the Tamil detainee Russell and of his inability to present a consistent or, for the Refugee Review Tribunal, credible story is much more effective and humane.

Like many, I am eager to see books challenge those who support John Howard’s policies on refugees and asylum seekers. Asylum is an important book, a valuable record, a call to people to respond, but it carries a greater burden than any historical work. This book explores state-inflicted damage and injustice that will continue until people, including readers of this book, demand that it changes.

Despite its direct impact on me, I asked myself throughout how Asylum would read to someone with a high level of hostility towards detainees. Could this book make a difference to such a reader? Yes and no. Tyler’s tone, especially in the earlier stories, is attuned to the reader’s possible disagreement. We have a sense of her being on the back foot, almost pleading at times for the compassion a story clearly warrants but she knows often does not get. Her outrage is clearly expressed; on occasion, this makes the book easier for hostile readers to dismiss.

On the other hand, one of the book’s great strengths is Tyler’s personal involvement with her subjects. Where this is presented through actions, rather than tone, she becomes an example: one writer, one mother among several, whose family becomes involved and whose life is changed. Her daughter’s letter to the immigration minister on behalf of Morteza presents a more challenging voice than any plea for compassion.

The people whose stories Tyler tells become more real as we observe them in a relationship with her. It is hard to dehumanise someone, package them as among an undifferentiated ‘batch’ of ‘failed asylum seekers’, once we are aware that they are loved, that they live in a unique relationship with another person whose individuality we fully accept. Tyler’s relationships with her subjects are the book’s most profound challenge to the hostile reader.

However, as the title flags for any browsing reader in a bookshop, this is a book written more for those who are seeking knowledge of, and connection with, the human beings in detention, rather than for those who are denying their equal humanity. For the increasing numbers of people who are disturbed by what they suspect is going on in detention centres, but who have little or no contact with detainees themselves, this book will be a way to meet them and to know their stories, and these readers will be encouraged to try harder.

Direct contact with people’s stories is one of the most potent counters to the prevailing climate of fear and dislike. Stories individualise, give voice, and bring people close to us. Stories also draw us in, so that we want to know more. Every detainee I encountered in the pages of this book has an ongoing story that I now want to explore. This is a testament to the role stories play in countering dehumanisation and generalisation; but it is also a testament to Tyler’s passionate journalism and skilled storytelling.

Comments powered by CComment