- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Angel in the House

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For some long-forgotten and surely misplaced medical reason, I was forced as a child to take spoonfuls of vile white poison called Hypol. It may have had some sinister connection with cod-liver oil – I no longer know or care. I mention this arcane information because Robert Macklin’s memoir War Babies, is the first example know to me of Hypol’s appearance in a literary work. I don’t recall anyone else mentioning ‘the Rawleigh’s man’ from whom my mother, not liking to send this hawker away without a sale of any kind, would buy jelly crystals.

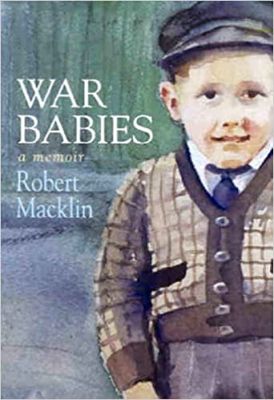

- Book 1 Title: War Babies

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Pandanus, $34.95pb, 242pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In evoking these very early years, Macklin offers a spectacle recalling Dirk Bogarde’s childhood memoir, Great Meadow (1992); it quite rigorously eschews adult comment on the child’s perceptions. Of course one accepts, as Macklin says at the outset, that ‘[t]he writer will seek a pattern, a narrative’, and this does emerge, but for me the best part of the book is in its first half as he recreates life in his Brisbane suburb, close to the adored mother Hilda May, while the father is off at war, leaving her reluctantly to go to school: ‘Then the war ended ... and the men came home and everything changed.’

In the first one hundred pages, it is a little hard to know what to make of the father, since Macklin has, to this point, recreated everything through Robbie’s eyes, but, as will become clearer, the relations with each parent (and between the parents) will be a crucial part of the ‘pattern’ that emerges. Early on, though, there is a wonderful freshness about the child’s observations, as though he is simply putting down what he saw without comment, as for instance when Cecily Burton ‘told me to pull up my pants leg to see my thing and she showed me hers. I was very surprised. I didn’t know what to think.’ Or when Carollie Cox, in an orgy of map decoration (blue colouring on the Australian coastline little bunches of sultanas stuck in the Irrigation Area), went too far and put pictures of the Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret in the Northern Territory and the teacher ‘held it up in class and made her cry’.

This first half is direct, sensuously exact and unadorned. Suddenly the tone changes to one of a narrating adult as Macklin chronicles the travails of another war baby (World War I this time); the loving, laughing, singing Hilda May, who proves to have a history of almost Dickensian grimness. It involves the shame of illegitimacy; the cruelty of the British class system round the turn of the twentieth century; a mother who has been the victim of both, and of a harsh mother herself, and who, as Hilda May Macklin, has reversed this cycle of vicious rejection by becoming indeed the angel in the house. Further pattern is suggested (but not explored) in the way Robbie’s father, damaged perhaps by the war and too fond of the booze, can barely sit in the same room as his own mother, the sanctimonious Grandmother Macklin.

Much of this is poignant and painful, but I wish that, having left the child’s voice behind, as he no doubt had to, Macklin had concentrated more single-mindedly on exploring the patterns he seems to have discovered. The stuff about his successes at school cricket (I know, and John Howard would probably agree, that it’s un-Australian not to relish protracted accounts of cricket matches, but there you are) and his social life among west Queensland landowners, when he goes off to jackaroo, is conventional and lacklustre by comparison. I admit that the account of killing a sheep to provide the shearers’ mutton chops for breakfast has all but made a vegetarian of me, but the unresolved equations of family life that send him off might have made even tougher reading.

Macklin is on to such a good thing in the near-magical rehearsal of childhood wonders and anxieties that the later material, unexceptionable as it is, seems ordinary by comparison. There are still potent moments, such as the meeting with the Aboriginal former film actor Robert Tudawali, but the boy and the mother and the sad, resentful father are at the heart of this affecting memoir.

Comments powered by CComment