- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Surviving the Unspeakable

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Janina Milek – born in Poland in 1921, shunted out of it with her parents and siblings by the Russians to become human draught horses in Siberia in 1940, released via Uzbekistan to a refugee camp in Iran in 1942, transferred to another refugee camp in Lusaka in Africa in 1943, and shipped to Australia in 1950 – told Tim Chappell that her family was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. When she finally had some kind of say as to where she might live (an Australian commission offered places to healthy persons from the African camp), the one thing she knew was that she would not go back to Poland and live ‘on the back of an old woman’s tongue’ (Janina’s marvellous phrase for gossip mongering). Her mother, to whom Janina had been completely devoted, suddenly announced that she wanted only to return home. Janina was deserted by the one person she now lived to care for.

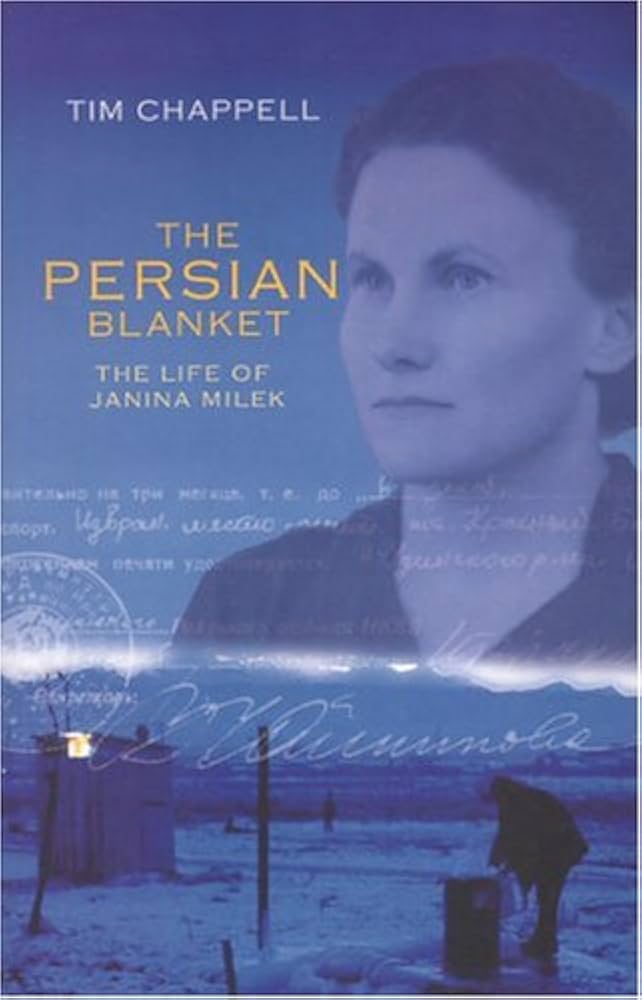

- Book 1 Title: The Persian Blanket

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of Janina Milek

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP, $24.95ph, 283pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Not Paradise

- Book 2 Subtitle: Four women's journeys beyond survival

- Book 2 Biblio: Hybrid, $27.95pb, 216pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

A deeply moral person, sometimes outspoken, but mostly silent and bent on working alone, Janina cleaned in hospitals and homes for years of her new life in Australia. Chappell, who has known her all his life and whose family sounds like a boon to any refugee, uses Janina’s words to tell the story. Chappell makes no extraneous comment except to intersperse the record with modest vignettes of his parents’ Samaritan contact with Janina. Thus, like the best oral histories, Janina’s is both matter-of-fact and remarkable, a kind of ‘fortunate life’ in the Faceyan sense.

The little measures of good fortune in Janina’s Australian life revolve around the Chappell family. Talking to the author’s mother about the hardships and hunger of her exiled life, Janina exclaimed that Australia is so different as to make her stories seem unbelievable. Then comes a characteristic, forthright explosion: ‘But oh these bloody Australians, all they are concerned about is sex education and sports!’

I was haunted by Janina Milek in a way I had not thought possible, even while being engrossed by her story. There is so much we do not know and will never know about her. Nothing she says into Chappell’s tape recorder is explained or analysed. This is a courtesy, not an omission; the not-knowing all of Milek is seductive and mysterious.

Strong, thrifty and astonishingly hard-working, Milek would have made a capable wife in the biblical sense, had she any notion of marrying. Basia, Erna, Jasia and Kitia, the four Jewish women whose post-Holocaust lives in Australia have been chronicled in Not Paradise, all married and each gave birth to one child, a son. Anna Rosner Blay’s chapter headings are taken from the Hebrew Scriptures and all from the last section of Proverbs. Proverbs, it will be remembered, extols wisdom and virtue, but this lovely section addresses the concrete beauty and goodness (Charles Johnson’s words, in his introduction to Proverbs in the Canongate Books edition of the King James Bible) of the capable wife: ‘Strength and dignity are her clothing; She is like the merchant ships; With the fruit of her hands; She planteth a vineyard.’ Mrs Beeton quoted from this same part of Proverbs at the opening of her nineteenth-century English bible on household management.

Not Paradise (‘The forest unmasks exile: it is not paradise or heaven, but a foreign land’ is taken from a description of Daniel Libeskind’s Garden of Exile and Emigration) is, by happenstance, similarly structured to The Persian Blanket. Each section of oral history is followed by a version of a changing chorus. Rosner Blay, herself the daughter of Holocaust survivors, tells a different and personal story of survival: that of the breakdown of her 33-year-old marriage. She makes a persuasive case in her prologue that to examine this fifth and unannounced story is not out of place in a book about post-Holocaust lives, but, in the exposition, I for one am far from convinced. In its swampy, personal and present tense, it seems superfluous and even deceitfully included.

From chapter headings to last page, Not Paradise is highly wrought. Rosner Blay has unstitched memories and pain takingly embroidered and appliqued them into a mosaic (her word) of specific Proverbial themes. She is always present as the listener always commenting on the emotions and demeanour of her storytellers who, as first-generation Holocaust survivors, are in their eighties. While the subject matter of both books is sui generis and never comparative, literary demeanour is a legitimate concern and affects the way we respond to records of suffering and trauma. Again and again, I wanted to listen to Basia, Erna, Jasia and Kitia without an intrusive crutch. Listening, literally incorrect, is a much more accurate verb in the case of personal stories; I wanted to listen uninterruptedly to these four strong women.

In contrast to this visceral, sceptical response to the extremely self-conscious methodology of Not Paradise, it is an act of imagination on Rosner Blay’s part to remind us of Arthur Calwell’s postwar immigration policy (Calwell encouraged Jewish immigration at first, but within two years humanitarianism was not an acceptable motive) as we live with the queue-jumping pejoratives of the Liberal government. It was shocking to find that two titles which seemed on first sight to refer to present dangers should turn out to be stories of exile and emigration and tentative, partial welcome to Australia over fifty years ago. Repeatedly, the women who speak to Rosner Blay comment on the incredulity in 1950s Australia that anyone might speak a language other than English. Erna, survivor of the Warsaw ghetto and seven camps, including Ravensbrück and Dachau, remembers learning enough English to laugh at a woman in a butcher’s shop asking for ‘language’ instead of ‘tongue’.

When people who are old tell their stories, we catch our breath that they have trusted their listener enough to speak about their lives before it is too late, and, in these cases, to speak about rebuilding their lives after surviving the unspeakable. This trust is central to our sense of privilege in hearing the stories. Kitia Altman, Jasia Romer, Erna Rosenthal and Basia Schenkel remind us that the sum of their histories, the tentative and difficult beginnings of their lives in Australia, is not only Jewish history but a part of Australian history, and inextricably caught up with political decisions.

Comments powered by CComment