- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Food

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Naked Garnish

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Gay Bilson, in her Plenty: Digressions on Food, is good on garnish. She describes the occasion of the queen mother’s tour of this country in 1958, during which the royal visitor ‘was offered white-bread sandwiches in the shape of Australia, with a sprig of parsley at the south-eastern tip, thoughtfully representing Tasmania’. Bilson understands, wisely, that the anecdote speaks for itself, and requires not further garnishing from her. Instead she reflects on the strange resilience of the parsley sprig, and the way it keep turning up on plates, decade after decade, as a signal to the diner that the dish had been composed by someone with an interest on how it looked on the plate; that somebody in the kitchen was taking the trouble, even if only to the extent of adding the sprig of parsley that had been sitting patiently in chilled water, waiting for its big moment.

- Book 1 Title: The Cook's Companion

- Book 1 Subtitle: 2nd edition

- Book 1 Biblio: Lantern, $125hb, 1136pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

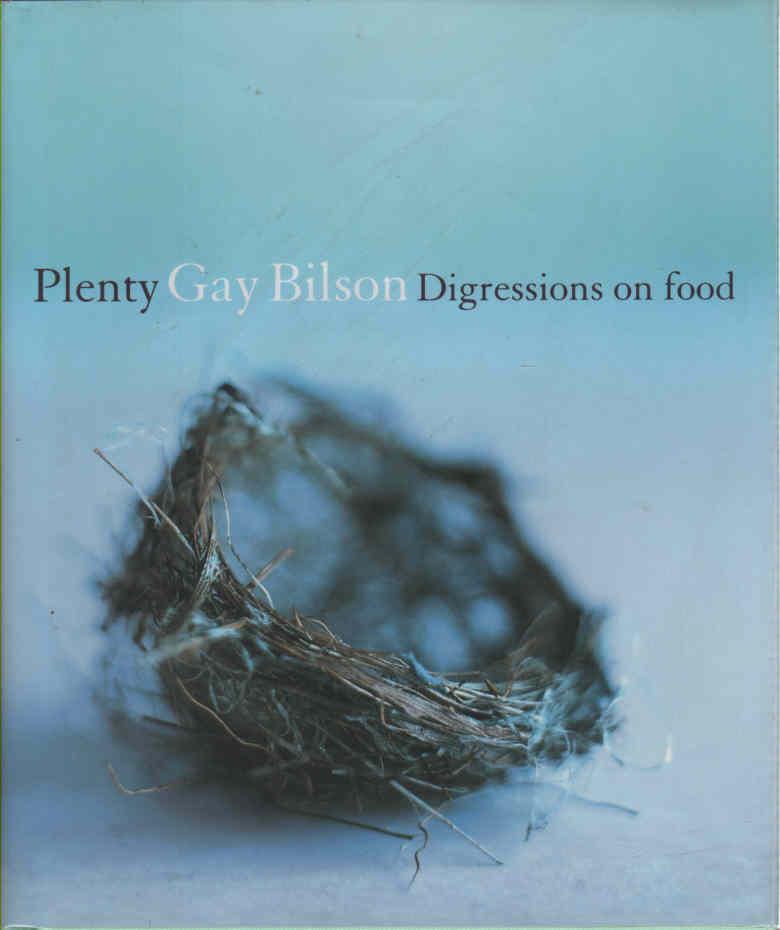

- Book 2 Title: Plenty

- Book 2 Subtitle: Digressions on food

- Book 2 Biblio: Lantern, $49.95hb, 320pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Garnishes are tenacious, surviving long after the main courses have been overtaken by fashion. The fanned strawberry, for example, can still be seen, an archaeological reminder of a culinary revolution that took place in the 1970s. It is fashionable now to deride this revolution, seeing nouvelle cuisine as an aberration or a distraction from the main game, rather than for what it was, a clearing of the decks that generated an entire rethinking of the process of cooking and of what dining – fine or domestic – was all about. Bilson is funny on the excesses of nouvelle cuisine, recalling a meal in Paris in the mid-1970s in which she rapidly demolished two towering chives that had been stuck to an island of mousseline: ‘I blushed for the chef,’ she recalls, ‘and ate them as quickly as I had vowed to eat all parsley garnishes.’ But she also recognises the significance of this culinary phenomenon, and the fact that it was not, by any means, all about the look and the garnish.

For Bilson, nouvelle cuisine was not really a revolution. Nor was it, so to speak, a flash in the pan. It was a reformation, a reassessment that helped to restore the ‘legitimacy’ of French cooking. She offers in passing a corrective to the now-diminished reputation of one of the true authors of nouvelle cuisine, Michel Guérard, rightly identifying his La Cuisine Gourmand as ‘the great French cookbook of the second half of the twentieth century’. Indeed, Bilson is scrupulous when it comes to giving credit where credit is due. In recalling her eighteen years at the legendary Berowra Waters Inn, Bilson’s mentors (including her former partner Tony Bilson), her fellow cooks, the waiters and the kitchen staff, and the suppliers and the odd-jobbers and the punters (in both senses of the term, given that the restaurant was accessible only by water), all come in for their share of praise. It is the generosity (and no less genuine for that) of a stage or film director who thanks the cast and the crew and the loyal fans and even the best boy electric, but who knows, as we know, that none of it could have happened without her.

Director is the operative word. For Bilson, food is theatre, and the restaurateur is ‘the second most theatrical of professions’. She recalls the early success of the Sydney restaurant that she opened with Tony Bilson in 1973, Tony’s Bon Gout. ‘We found an audience, or the audience found us.’ She has been finding audience, or audiences have been finding her, ever since. There is enormous pressure to keep that audience interested and coming back for more. One way of doing that is with spectacle and special effects, and Bilson has accordingly earned a place as one of the exemplars in a branch of theatre Australia has made its own, the Managed Event. In 1991 she presided over a fundraising banquet, the high point of which was a giant ice cream in the shape of a ‘medieval spiked weapon ... that was carried down the length of an enormous rectangle of diners by twelve naked, clay-smeared men and women’. It sounds like garnishing gone mad, but then maybe you had to be there.

More controversially, as the coup de théâtre for the Body Dinner at the 1993 Symposium of Australian Gastronomy, she conceived the idea of making sausages from her own blood. It seems to have been an attempt to take the director’s role to its ultimate conclusion, to incorporate herself, quite literally, into the production, as the invisible but all-present creator. Word of her intentions got out, and outrage ensued, as Bilson must have known it would. There was commentary both hysterical and thoughtful, but nobody could be found who thought that it was unequivocally a good idea. Nor, in the end, did Bilson, who concludes her recollections of this odd episode in Australian culinary history by declaring, not altogether convincingly, that ‘to simply chew on the idea and measure the reactions, may have been enough’.

If all this makes Bilson sound merely fashionable, or inventive for the sake of being inventive, it is a misleading impression. Just as she sees nouvelle cuisine as having reasserted the legitimacy of traditional French cooking, so she sees her signature dishes – brioche with poached bone marrow, braised shallots and red wine butter, for example – as harking back to the tastes of her childhood, when she ‘loved to pick out the amourette from the mid-loin lamb chops that formed the centre of my mother’s severely restricted menu’. There is comfort in repetition, and Bilson takes pride in being able to repeat the performance again and again. Notwithstanding her fascination with garnish, she never loses sight of what constitutes the essence of food and good eating, the ‘legitimacy’ – there is that word again – of the dish itself. ‘Lack of garnish,’ she says of Berowra Waters Inn, ‘is common to the three dishes we never took off the menu.’ Decorating the plate is one way of saying that an effort has been made, but real effort reveals itself in the dish, and requires no dressing up.

Like most directors, Bilson does not have a high opinion of critics. There is a ‘necessary pact between cook and diner’, and the critic is merely an intruder, spoiling things for everybody. She is hard on food writers generally, dismissing in a resonant phrase ‘the ersatz legitimacy of current cookbooks’ while acknowledging the influence of the greats, such as Elizabeth David and Alan Davidson. But not, interestingly, M.F.K. Fisher, whose reputation she questions, yet whose fey but acerbic style strikes me as having much in common with her own. (Her view that five is the ideal number at table is one that she shares with Fisher.) ‘My own prose,’ she says ruefully, ‘sometimes veers towards the Fisheresque.’ She is being her own critic here, and a harsh one at that. Bilson’s prose, Fisheresque or not, captures the fascination, the rewards and indeed the fun of cooking, and her unstoppable determination to go on with the show.

Among the cookbooks that Bilson does find indispensable is Stephanie Alexander’s The Cook’s Companion, which she sees as being as much a ‘personal encyclopedia’ as a cookbook. Not, as she laments elsewhere, the kind of ‘fraught, post-modem, open-ended’ encyclopedia that somehow never quite tells you what you need to know, but the kind that gives you the facts and ‘a sensible amount of instruction’. The Cook’s Companion (first published in 1996) has just been reissued in a revised and expanded form, and it does indeed tell you pretty much everything you need to know. If Bilson is a director, Alexander is a scriptwriter, and it is a testament to her influence that many thousands of people have learned to cook, or learned to cook properly, by following her scripts. But as Bilson and Alexander would no doubt agree, while you can achieve a lot by following the instructions, you cannot guarantee a perfect result that will please everybody. In the end, there is no accounting for taste. ‘I love baked bananas,’ says Alexander in introducing her recipe for baked bananas with meatloaf, but ‘my children think they are awful’.

Comments powered by CComment