- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Post Mortem

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is sobering to read these two optimistic works about a man of promise, written in mid-2004, in the light of their subject’s defeat in October 2004. Neither author was convinced that Latham could win. Barry Donovan has too much experience of the vagaries of the electorate to be anything but cautious, though he concludes with the hope that ‘the Lodge may yet have a prime minister’s young kids bouncing around in it before Christmas’. Through Margaret Simons’s essay runs an undercurrent of doubt about such a possibility, and she identifies Latham’s Achilles heel: ‘For decades, voters have been told that the main job of politicians is to manage the economy ... [and] I doubt if Latham will be able to convince them that it is now acceptable to vote on the basis of social issues, and the concrete things that directly affect their lives.’

- Book 1 Title: Mark Latham

- Book 1 Subtitle: The circuitbreaker

- Book 1 Biblio: Five Mile Press, $34.95hb, 288pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

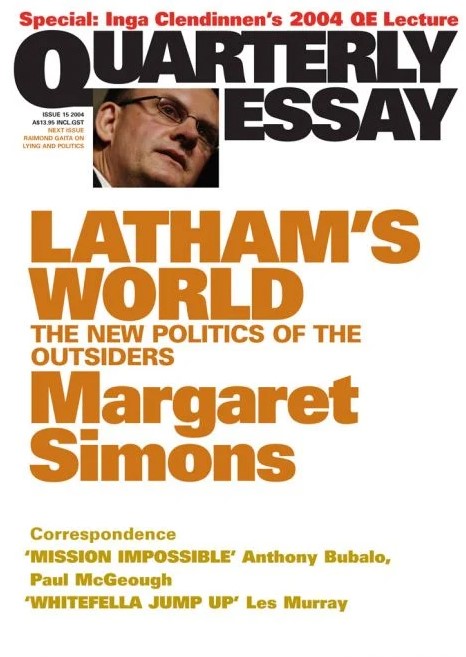

- Book 2 Title: Quarterly Essay

- Book 2 Subtitle: Latham's World

- Book 2 Biblio: Black Inc., $13.95pb, 150pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Both studies examine the Whitlam-Latham relationship. Donovan is content to quote Whitlam’s praise of Latham, instances a funny spoof profile of Latham full of Whitlam references, mentions the ‘political-father-and-son association’, and makes the important point that Whitlam’s suburban and families policy emphases provided a ‘template’ for Latham. Simons delves much deeper into Whitlam as Latham’s ‘second father’ and Latham as ‘the honorary fifth child’ (Nick Whitlam’s description), explores the older man’s role as ‘tutor’ (Gough’s word, according to Simons) and seeks to understand the mutual attraction between the two men. She pushes the policy template further than Donovan, and, though much less given to quotation, leaves us with the most memorable remark on the relationship: ‘If Mark becomes prime minister, I think Gough will die soon after. He will see his life’s work as being complete.’

The clearest contrast between the authors is in their treatment of the allegations of Latham’s mismanagement and fiscal ineptitude as mayor of Liverpool, allegations that surfaced in the middle of the year and that dogged Latham throughout the election. Both agree on the significance of Latham’s transformation of the infrastructure of Liverpool: Donovan lists his capital projects; Simons reports that ‘it is hard to imagine Liverpool without the capital works Latham built’. But Donovan is content to refute the allegations by simply quoting at length (nearly three pages) Latham’s parliamentary defence and merely noting that for ‘most observers ... it was an effective rebuttal’. Simons is more sceptical. As a result of dogged research, she concludes that Latham, in his defence, ‘had been deceptively selective in his use of figures ... [although] Latham’s critics have been misleading as well’. In her detailed analysis, she suggests that there were problems with the implementation of his purchaser-provider initiatives – probably let down by council management – and that they ultimately did not bring the anticipated financial returns, though this may have been in part the result of Latham’s departure from the council. Nevertheless, these failures were ‘not the whole or the main reason for council’s fragile condition in the mid-1990s’, which was the basis of the government’s charges.

These examples hint at the problems with Donovan’s opus. It is a booster book in the truest sense: over one-third of the book – some 100 pages – are simply great slabs from Latham’s major speeches and writings, with an occasional editorial interpolation. In addition to Latham regurgitated, Donovan has some forty pages of interviews, reproduced apparently verbatim; some, particularly those with Simon Crean and Julia Gillard, are particularly insightful. Given how little known Latham was, it could be argued that there was a case for putting this primary material into the public domain but scarcely between hard covers in a handsomely produced book.

Both writers are excited by Latham’s ideas; indeed, for Simons, it is the major focus of her work. Donovan presents those ideas; Simons wrestles with them. Both find his magnum opus Civilising Global Capital (1998) – or the ‘Thoughts of Chairman Mark’ (dangerously flippant Donovan!) – tough going, and show that much that is relevant in that book can be found in jargon-free prose in his later works. Both writers are members of what Chris Feik has ironically labelled ‘the latte-sipping enemies of the people’, and are uneasy with Latham’s dismissal of the left-leaning middle class implicit in his critical insider/outsider dichotomy. Simons, who is excellent on the model’s analytic power, fears that it may mean a continuation of the smearing of the elite that has characterised the Howard years, while Donovan suggests a contradiction by instancing Peter Garrett, Latham’s star recruit, as an example of a classic insider.

But this focus on Latham the ideas man gives rise to a puzzle. Why has Latham’s year-long leadership of the Labor party been so strangely superficial? While Simons would probably not accept my characterisation, she does suggest that, insofar as Latham, as leader, has given up communicating his ideas, it is because ‘he has succumbed to the toxic climate of public life’, with its denigration of ideas. A more pragmatic reason is supplied by Donovan, who hints that some of Latham’s party critics would like to see his ideas put ‘away in the Latham personal filing cabinet’.

What, anyhow, do I mean by ‘strangely superficial’? I do not mean the gimmicks with which he began 2004: the bus jaunts, the reading to kids, the talking to babies, the visits to the Big Brother set, the speeches that avoided the prevailing partisan agenda, a process whereby he threatened to become, in Paul Kelly’s words, ‘the social therapist to the nation’. I agree with Donovan that such tactics were imaginatively appropriate for a politician desperate to establish a leadership profile in less than a year.

What I do mean are some critical but rather glib pledges and the belated appearance of major policies. Donovan provides a sturdy defence of Latham’s promise to bring the troops home from Iraq by Christmas, and instances ways in which the media and his opponents misconstrued this pledge. But both Latham and Donovan justify the pledge on the basis of their opposition to the Second Iraq War. I share their view that the invasion of Iraq cannot be justified as a measure against Islamic terrorism. It has done little to contain terrorism; rather, it has fomented terrorism in Iraq, in the wider Middle East and in the world. But a country cannot participate in bringing down a régime, as Australia did, and then not participate in trying to put the pieces back together. There may come a time when the cost in blood, treasure and diplomacy may outweigh the effort at reconstruction, but that time had not come in mid-2004.

In the same category, I would place the pledge on the Tasmanian old growth forests: off-the-cuff, poorly executed and, in this case, last minute. These two decisions may reflect the fact that Latham has given little thought to foreign policy or to environmental issues, at least outside the suburban environment. Simons notes that foreign policy is ‘surely in most respects one of his weakest areas’, while Bob Brown told her that he had ‘got the impression that Latham had never really thought about the environment’.

But the charge of superficiality draws greatest weight from the tardy appearance of so many key policies. How much blame should attach to Latham would depend very much on the state of policy development under his predecessor. But late presentation meant that the tax and family policy got caught up in a controversy over a side issue and then there was insufficient time to hammer home its merits. Medicare Gold was the genesis of a good idea, but there was no time to explain how it fitted into a more systematic overhaul of the health system. And if the party is going to have a hit list, as in education, get out the hit list well before the election. We did so in the early 1980s with the original Medicare, and the self-interested protests of those on the hit list helped mobilise the forces for reform.

Donovan defends Latham’s refusal to issue major policies early by instancing the fate that befell the Coalition with ‘Fightback’ in 1991-93. But this case will not do, for all it suggests is that it may be political suicide for an Opposition to advance a new taxation system. Donovan himself quotes the alternative and, to my mind, valid view expressed by Whitlam in his introduction to Civilising Global Capital. ‘[In Opposition] the thing that mattered most was the renewal of policy and, with it, the renewal of the party’s relevance ... we were able to use those ... years [after 1966] to set the agenda for the nation.’ Indeed, Donovan is so impressed with this that he quotes it verbatim twice, on pages twenty and fifty-two. And he is right to do so. The only two occasions on which Labor has won from Opposition in the past half-century – 1972 and 1983 – it won with a structured programme, much of which had been long in the public domain. The Labor party has had no such structured programme over the past eight years. In 1998 it relied on denouncing the goods and services tax; in 2001 it opted for the small-target approach; in 2004 it got halfway there. This is the challenge now facing Mark Latham. He should be encouraged by the fact that it took his hero and tutor two tries for success.

Comments powered by CComment