- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Forcing Our Hand

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Since the end of the Cold War, foreign policy has become economic policy.’ It was March 1999 when I put this cliché du jour to a British bureaucrat handling policy about cultural industries and trade agreements. The World Trade Organisation was young, the New Economy was everywhere, the NASDAQ still had 3000 points to rise. But we were walking across Trafalgar Square, Nelson was watching and I should have known better. ‘That,’ she said tolerantly, ‘is what they told us in 1948.’ As we spoke, NATO forces were at war. Bill Clinton, who had won the first US election since the Cold War by reminding his predecessor about the economy, had decided that force was now required in the Balkans. He’d already apologised for not using it in Rwanda. Two-and-a-half years later, the mutual defence provisions of Australia’s military alliance with the US would be activated for the first time. The Cold War was over, but there would be plenty for diplomats to talk about besides trade deals and prosperity. Later in 1999, the collapse of the Seattle ministerial meeting of the WTO showed that even economic policy was going to be hard work.

- Book 1 Title: Fatal Attraction

- Book 1 Subtitle: Reflections on the alliance with the United States

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $24.95pb, 185pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

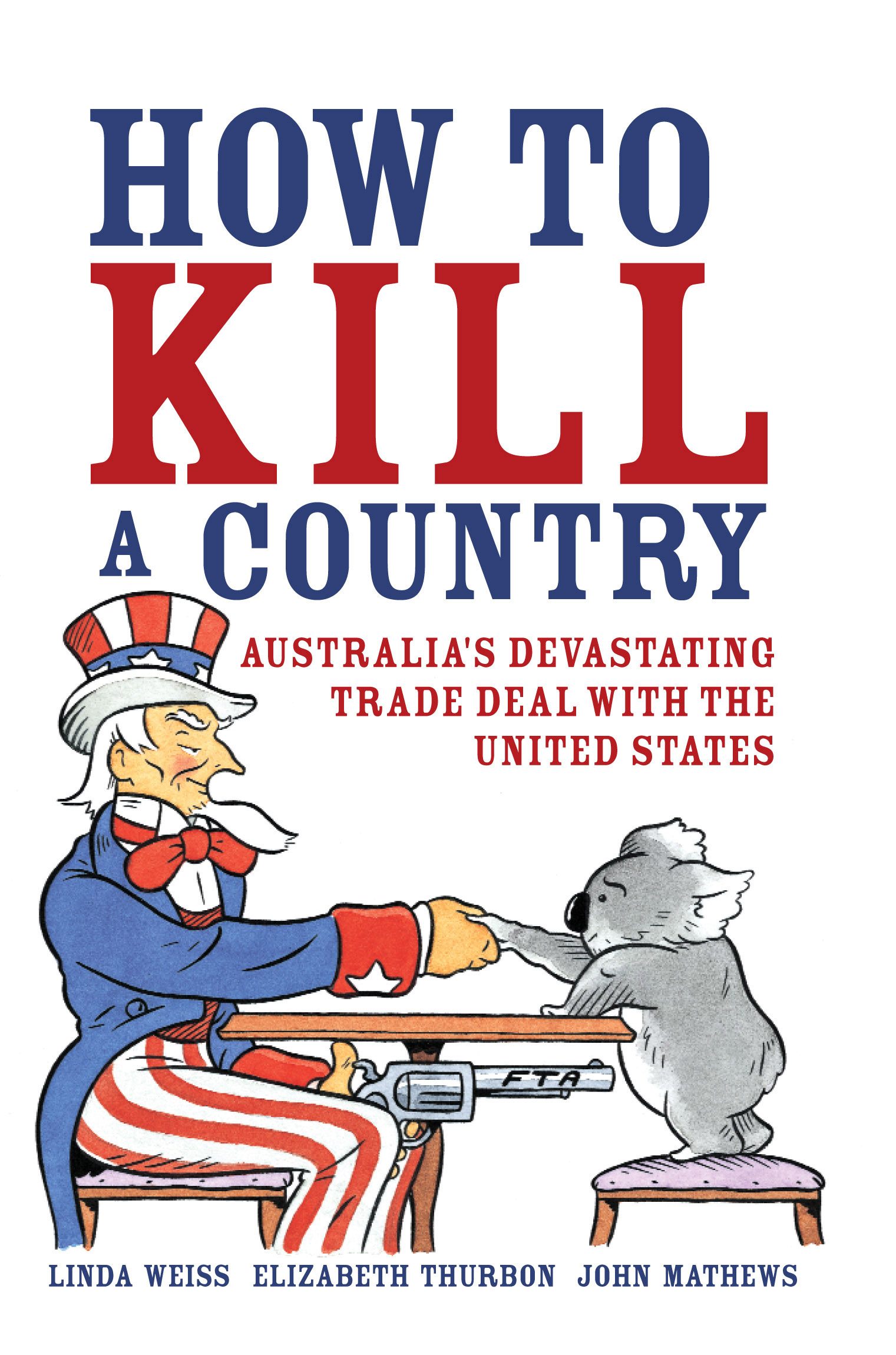

- Book 2 Title: How to Kill a Country

- Book 2 Subtitle: Australia's devastating trade deal with the United States

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.95pb, 190pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

For Bruce Grant, the 1990s offered an opportunity to dismantle the machinery of war and revisit ‘issues of global governance and human rights, health, education and prosperity ... that had been left on the table after the Second World War’. Under the new order, security would reside in mutually beneficial arrangements reached by agreement, not force. The United Nations, freed of bipolar dysfunction, might finally work.

Australia. already more confident of its ability to defend itself in anything but a major war, could think about things other than ‘shoring up the power or prestige of a protector’. A ‘golden period’ of statecraft ensued, says Grant, who co-wrote a book about the era with Foreign Minister Gareth Evans: the Cambodian peace initiative, the development of the Cairns Group and APEC. The third Hawke government’s addition of Trade to the Department of Foreign Affairs gave economics a bigger place in diplomatic agendas.

Fatal Attraction condemns what came next, especially the current political leaders who seem unaware of ‘either the complexity or the promise of the contemporary world’ and are determined to ignore or even defy ‘what has been slowly emerging as an alternative to world order based on military power’. Bush and Howard represent ‘a traditional approach to statecraft and the projection of power that has been losing authenticity for half a century’. It is a familiar argument now, but Grant puts it elegantly. The response from the Bush-ites, of course, is equally familiar: ‘September 10 mindset.’

Grant is not a critic of the alliance. Australia benefits, he says, through America’s power and influence in the world, its industrial and scientific magnetism, its contribution to stability in the Asia-Pacific region and better record on human rights than most countries there, the intelligence links and defence-on-the-cheap it offers. His complaint is about Australia’s elevation of the alliance ‘to a status that is exotically high. It has become the Eleventh Commandment of Australian politics, rather than being respected for what it is, an important instrument of Australian security which is, in turn, one component of our national interest. A valuable asset has become the treasury itself.’ He is also concerned about the values implicit in the rearticulated relationship. ‘Over time,’ he says, ‘the way a country uses force to protect and promote its interests begins to shape its identity.’

The recipe? Learn from the mistakes of Iraq: not isolationism but the need for ‘more allies of the integrated variety, with whom we can work to manage the turbulence’. Boost Australia’s diplomatic resources, overhaul the intelligence relationship with the US, be more sensitive to the special conditions in Australia’s region when dealing with terrorism, adopt Australia’s multiculturalism more rigorously as a national strategy. Most importantly, take the political heat out of the alliance, which ‘is in danger of becoming not just a security arrangement between two countries but a test of how as Australians we see ourselves, the world and the future’.

Turning down the heat is what How to Kill a Country doesn’t do. The authors argue that the trade agreement between the alliance partners is a ‘death sentence for Australia as an independent country’ that leaves it well on the way to becoming an appendage state’. Their attack is concentrated in several areas. Admitting US representatives into Australia’s decision-making about quarantine standards and the eligibility of new drugs under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme will lower quarantine standards and raise drug prices. Allowing Australian companies to bid for US government contracts is a potential gain, but the authors think continuing restrictions will prevent Australian companies from actually winning them, and they oppose the dismantling of local purchasing preferences in Australia. Adopting much US intellectual property law will favour the US, the world’s dominant producer, and cost Australia a net importer of these products.

Especially valuable is the book’s discussion of Australia’s earlier rejection of some proposals adopted in the agreement. Australia gave ground to the US that it was not prepared to give to other trading partners in less charged negotiating circumstances. It is not clear that the gains elsewhere in the negotiations justified this. The book also criticises the handling of the negotiations by the Australian government, which the authors say was much less open about the content of the deal than its US counterpart.

This agreement is effectively a new constitution for a globalised Australian economy and society. It demands much more analysis than it has had, so How to Kill a Country is welcome. Unfortunately, the book overplays its hand at times. Australian governments might be removing their Buy Australian preference, but they haven’t substituted Buy American. Intellectual property companies can’t simultaneously ‘make or produce nothing’ and be the future of the information economy. By concentrating on what Australia gives up rather than on what it may gain, it becomes too easy for the agreement’s supporters to reject the book’s analysis as inward-looking. A more balanced assessment of the deal could spend more time on Australia’s failure to secure a better agreement on agriculture, the impact for manufacturing, and the many competing estimates of the net economic benefits of the deal, without weakening the argument.

The tough puzzle for the authors of these two books is why their arguments were rejected or ignored by the electorate. Grant says that Australia’s military alliance with the US ‘overwhelms our political discourse’, but that’s not what the exit polls suggest. Linda Weiss, Elizabeth Thurbon and John Mathews say the free trade agreement was sold to the public by the bribery of rural industry adjustment funding and the bullying of opponents and the media. Like all trade agreements, it was hideously complex, and criticism of it was treated as criticism of the alliance.

The free trade agreement was a product of an unusual moment. Not since Robert Menzies and Dwight Eisenhower have a pair of conservative leaders in Australia and the US had so much time to work together. Howard raised the possibility of an agreement with Bush in Washington on 10 September 2001. The Australian mindset was keen, the American cautious. The world changed, but the negotiating dynamic didn’t. As both countries approached elections, Bush could afford to drop an unsatisfactory deal even with a loyal ally. Howard, however, had raised the domestic stakes high, on both the alliance and its economic dividend. Announcing the dividend was more important than its size. For Australia’s trade negotiators, some of the most pragmatic people going around in a pragmatic country, the one option that wasn’t available was the one they’ve had to deploy so often before – walking away from the table.

These books are about power, which will force many an economic hand yet.

Comments powered by CComment