- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Prized Lands

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Aspiring Australian writers lament the fact that few publishers are accepting unsolicited fiction manuscripts. Those that do accept them lament the fact that they are inundated by around a thousand submissions each year. What’s the solution? Increasingly, it seems, awards for unpublished work with publication as the prize. Writers know their work will at least be looked at; publishers can outsource to judges the culling of what would otherwise be their slush pile. It is no longer just the 24-year-old Vogel Award, with its promise of publication by Allen & Unwin. State-based awards now guarantee publication by UQP, FACP and Wakefield Press.

- Book 1 Title: Drown Them in the Sea

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $21.95pb, 158pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

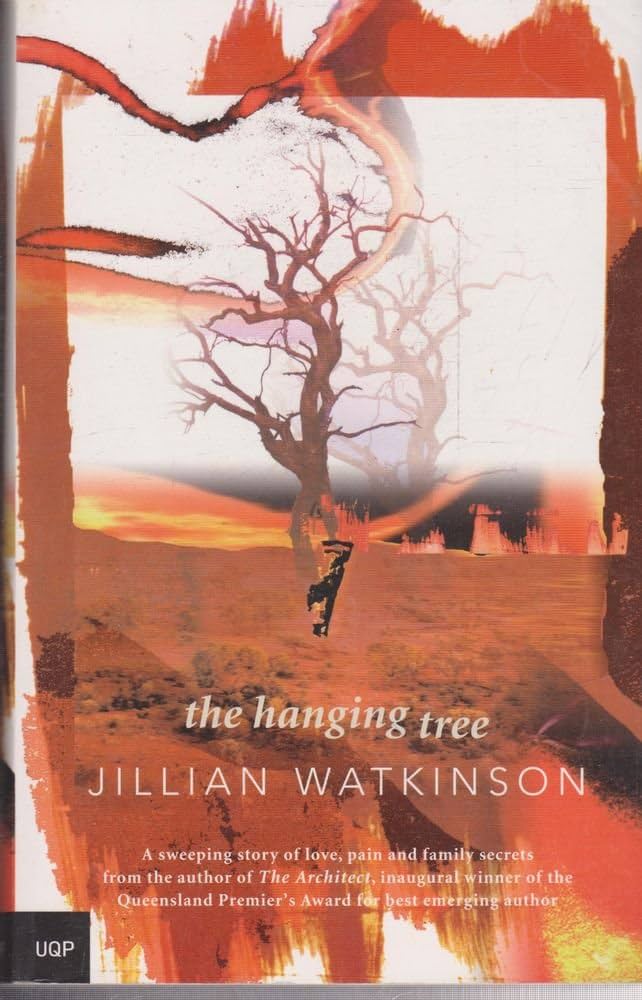

- Book 2 Title: The Hanging Tree

- Book 2 Biblio: UQP, $22.95pb, 323pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Neither book is crushed under that weight, but they bear up in different ways. Drown Them in the Sea is short, its narrative straightforward and linear, its ambitions modest. Twice as long, The Hanging Tree is hyper-aware of its own fictionality – it uses the circle as a metaphor for its own structure (and much else besides) – and wants to engage with as many ideas as possible.

Drown Them in the Sea begins with an epigraph from Jack London: ‘It crushed them … until they perceived themselves finite and small, specks and motes moving with weak cunning and little wisdom amidst the play and interplay of the great blind elements and forces.’ Here, then, is the major theme of Angel’s novel. His ‘speck’ is Millvan, owner of a drought-ravaged Queensland property, who can only watch as the fickle wind changes, depriving him of rain. Later in the novel, the wind swings and fans a fire out of control, and Mill van must seek safety in his property’s river. Earth, wind, fire and water, all the ‘great blind elements and forces’, are present. And then there’s the bank. The novel follows Millvan’s fight to maintain ownership of his farm, Arbour, as the bank demands repayments he cannot afford. The importance of mateship in a rural community is underscored by offers of help; but enmities also flare. There is a slow buildup of tension as the reader waits for imminent catastrophe.

What the London quote does not capture is Millvan’s love for the land that his father and grandfather owned, and his great desire to gift Arbour to his son Murray. For himself and his wife, Millvan dreams of a white cottage by the sea. Yet it is an ambivalent dream: he needs to be near the sea so that he can fish, and ‘[f]ishing kept his mind off things. It would stop him wanting to go back to the bush.’ But he can’t be too near the sea, for fear of being overwhelmed by the loss of familiar landscape.

To ensure that Murray can have the farm, Millvan must grow more wheat, extracting the last fecundity from the land, to pay back the bank. To grow more wheat, he must get rid of the trees along the river, trees that his grandfather left standing. The two strands of sentimentality clash. His desire for Murray to take over the property wins. There is uncertainty in the novel about whether the land can in fact be owned. The indifference of the elements suggests it can’t be, and Millvan thinks at one point of Murray as the next ‘custodian’, a word that obviously suggests caretaking rather than possession. But Millvan is never in doubt that the land is his – his love is proprietorial, and custodianship might be in the interests of future generations of his own family rather than the land itself.

Drown Them in the Sea invites the reviewer’s cliché ‘deceptively simple’. In fact, there is no deception: this is a simple tale. Angel’s achievement here is the depiction of the land and of life on that land.

Life on the land is very different in The Hanging Tree. This novel is also set on a Queensland property, but Tallaringa is a vast station, and its operation is not of central concern. The land here is mysterious, inhabited by ghosts, and the repository of stories. It hosts the mirage of the hanging tree, part of a secret Aboriginal Dreaming, but also a symbol that is connected to the myth of Prometheus, and with more disturbing literal associations. The land is ‘owned’ by the Masters family, but some feel that they belong to Tallaringa more than they feel that Tallaringa belongs to them. Jock Masters, the character who expresses this feeling most explicitly, isn’t even Australian-born. But most of the Masters family are Australian. Bill Masters, self-appointed chronicler of the family history, tells us: ‘In our family, the heritage is mixed and blurred ... We are – in alphabetical order – Aborigine, Afghani, Chinese, English, wild Irish and Welsh ... Now, in my generation, we’re all just Australian.’

Ostensibly, this is a history of an Australian family in which ‘children wandered between two cultures and blurred the generational lines’. If it weren’t so packed with philosophical concerns, one might even call it a saga. The narrative covers generations and certainly has drive, after an initial slow start. But Watkinson wants to do so much more than write a mere story. The Hanging Tree is about family, identity, race, gender, language, war, myth, memory, storytelling and more. If Angel’s achievement is in an uncomplicated evocation, Watkinson’s is in ensuring that her multiple themes do not sit awkwardly but are woven into the fabric of the novel.

Watkinson is also fascinated with damaged characters – whether psychologically, emotionally or physically – and with the possibility of healing. A similar concern is evident in The Architect. One of the healers – a mother figure and a lover figure, Jan Murray – appears in both books. Her arrival at Tallaringa, in the late 1970s, is the focus of Bill’s chronicle.

Jan is not the only character to appear in both The Hanging Tree and The Architect, but the two books can stand quite independently. It is as if Watkinson couldn’t help but imagine more about the lives of the characters in her first book, and felt driven to give them denser family trees and fuller histories. In The Hanging Tree, she is equally unable to limit the fictional world she created. It feels as though this is the book Watkinson has always wanted to write – apparently twenty years of research went into it – and that she desperately wanted to include everything she could. It is not just the weight of ideas that suggests this: sentences stretch out with her desire to convey more than story; incidental characters are given more space than they need; and dialogue can be implausible, with characters voicing philosophical ideas rather than chat. Still, this is ultimately a successful novel, absorbing and thought-provoking. If The Hanging Tree is struggling under anyone’ expectations, they are Watkinson’s own, rather than the reader’s.

Comments powered by CComment