- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Struggling in Fertile Ground

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Childhood is a fertile territory for writers. Almost all first-time authors hoe it, and some continue to do so for the rest of their careers. Given the chance, most people cannot resist the impulse to reminisce about the horrors and delights of being a child.

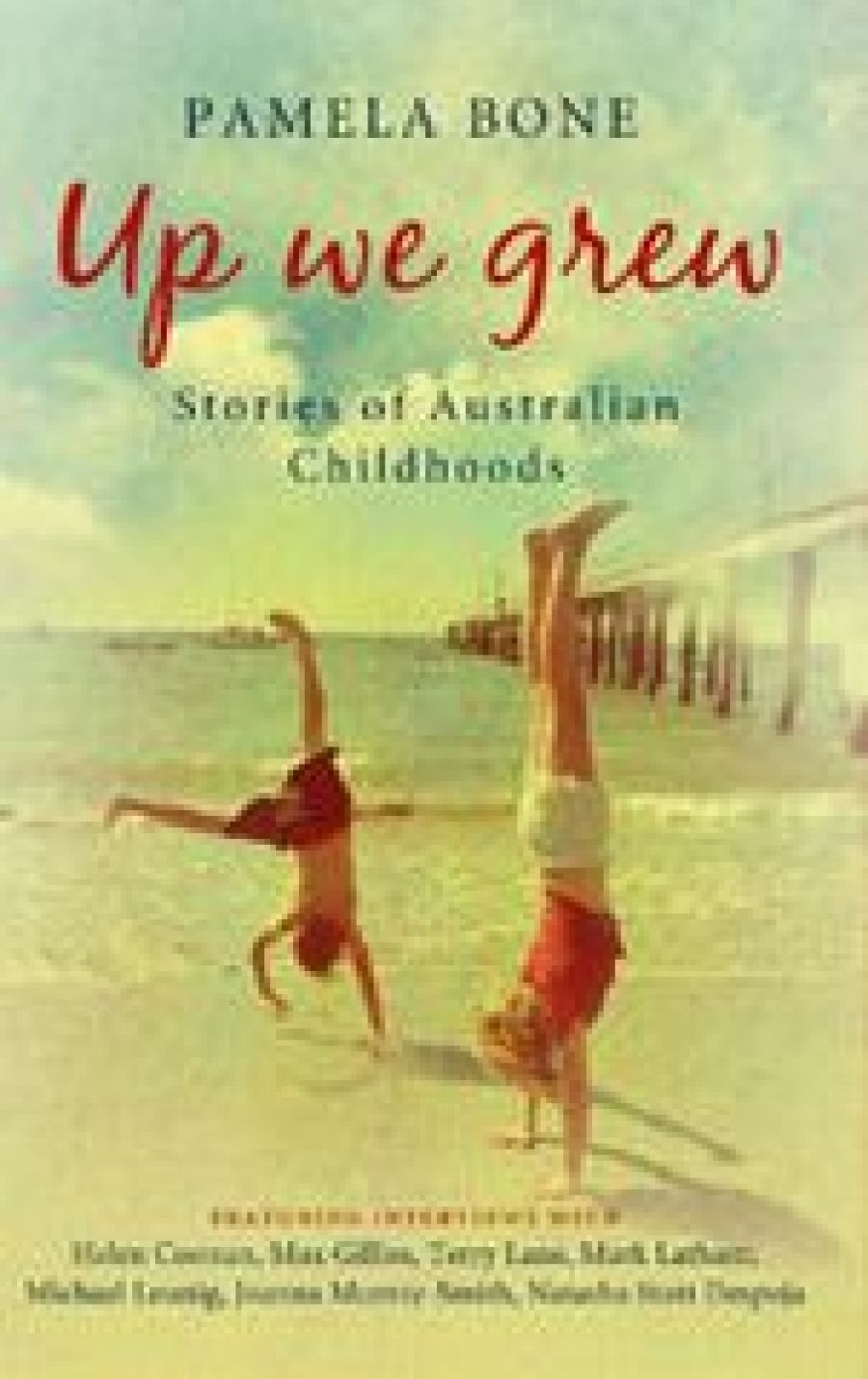

- Book 1 Title: Up we grew

- Book 1 Subtitle: Stories of Australian childhoods

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $29.95pb, 248pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Bone approaches the subject through memories of her own childhood and by interviewing dozens of people from a wide variety of backgrounds. What most have in common is that their early family life was a struggle, one way or another. How they responded to that struggle and how they learnt to live with its effects are what interest her. In part, Bone’s project is to grapple with the old question of nature versus nurture.

Bone starts with her own story. She grew up in Finley, just north of the Murray River, in a large poor family. She was ashamed that they didn’t live in a proper house, only an old shed; and she was ashamed of their poverty. A quiet child, more an observer than a talker, she hated school and consequently did not do well at it, but she enjoyed the freedom of the countryside and the company of her friends and siblings.

Bone’s mother always said that they weren’t poor, just broke. That says something about family expectation and self-image. Bone and her siblings have done well in life and have been ‘upwardly mobile’. Serious readers, they experienced other worlds vicariously. So, too, with many of Bone’s interviewees: reading was an escape, even a lifesaver.

Some of her subjects are well known, some not. In revealing their early influences, public figures such as Mark Latham and Natasha Stott Despoja show us how certain characteristics emerged quite early in life. 1t is easy to imagine Latham – the only son, determined to get on – bent over his school texts while his mother and sisters hovered in the background; or Stott Despoja, daughter of a feminist single parent, lecturing to fellow schoolgirls at her conservative Adelaide school on the rights of working women. There are glimpses into some fascinating lives: Terry Lane, for example, the adopted son of parents who were loving but very different from him. He must have been almost like a Martian in their midst. But one of the problems is that Bone assembles so many stories that they begin to bleed into one another. Rather than build an argument or even demonstrate trends, Up We Grew presents a mishmash of images.

What do we learn that is new? Not a great deal. Many people have awful thing happen to them; some survive, some don’t. Stott Despoja’s mother was a feminist and, lo and behold, so is her daughter; Latham grew up among battlers in public housing, and his vision for Australia is to give people opportunities so that they can improve their lot.

One person’s story told well – in depth and with passion – can tell us more than twenty potted biographies. In a sense, Bone has tried to do too much. Three or four wellchosen subjects, explored at length, would have left this reader with a far more satisfying sense of the complexities and variety of family life. Too much has been abbreviated. In places, a lifetime is condensed into a paragraph. For example, this, about former Victorian Arts Minister Norman Lacy:

Norman left the plumbing job and went to theological college, passed his Leaving Certificate, spent the money he had inherited from his father on getting a theology degree, became vicar of St John’s Church in Healesville, spent nine years altogether in the Anglican Ministry. While studying for his theology degree he lived in Ridley College, in Parkville, surrounded by leafy gardens, with students who had been to private schools, listening to classical music.

After a dozen of these, it all becomes a blur.

There is also some rather odd editing. Instead of breaks in the text being in the logical place – that is, to mark the separation between one story and the next – they are repeatedly thrown into the middle of a person’s story, sometimes at exactly the wrong moment. It is almost as if they have been put there to decorate the page rather than to aid the reader.

In relating people’s stories Bone touches upon historical events across a wide spectrum of time and place, from early twentieth-century Australia to Europe during World War II, from the stolen generations to recent refugee arrivals. Unfortunately, errors have crept into the text; this is poor coming from a university press. (One example: Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin in 1956 occurred some months before the Hungarian uprising, not after it.)

Ultimately, it is not clear from Bone’s researches whether a tough beginning builds resilience or corrodes it. Nevertheless, she believes that we are not totally at the mercy of events. Some children, it seems, are natural survivors. Certain things help: a sunny temperament, good looks, the love of at least one adult. Many people bravely shared their stories with Bone for this book, but it is unclear, at the end, what it all amounts to.

Comments powered by CComment