- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indonesia

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The False State?

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Why is it that Indonesia’s northernmost province has received so much less Australian attention than East Timor? Aceh is of course further away, and no claims are made about local people supposedly helping our soldiers during World War II. Another reason is the uniquely emotive issue of the deaths of the five Australian journalists in Timor in 1975. A suspicion arises that the main reason is that the East Timorese are Catholics while the Acehnese are Muslims. Many Australians, especially church activists, could feel something in common with oppressed fellow-Christians in a nearby territory.

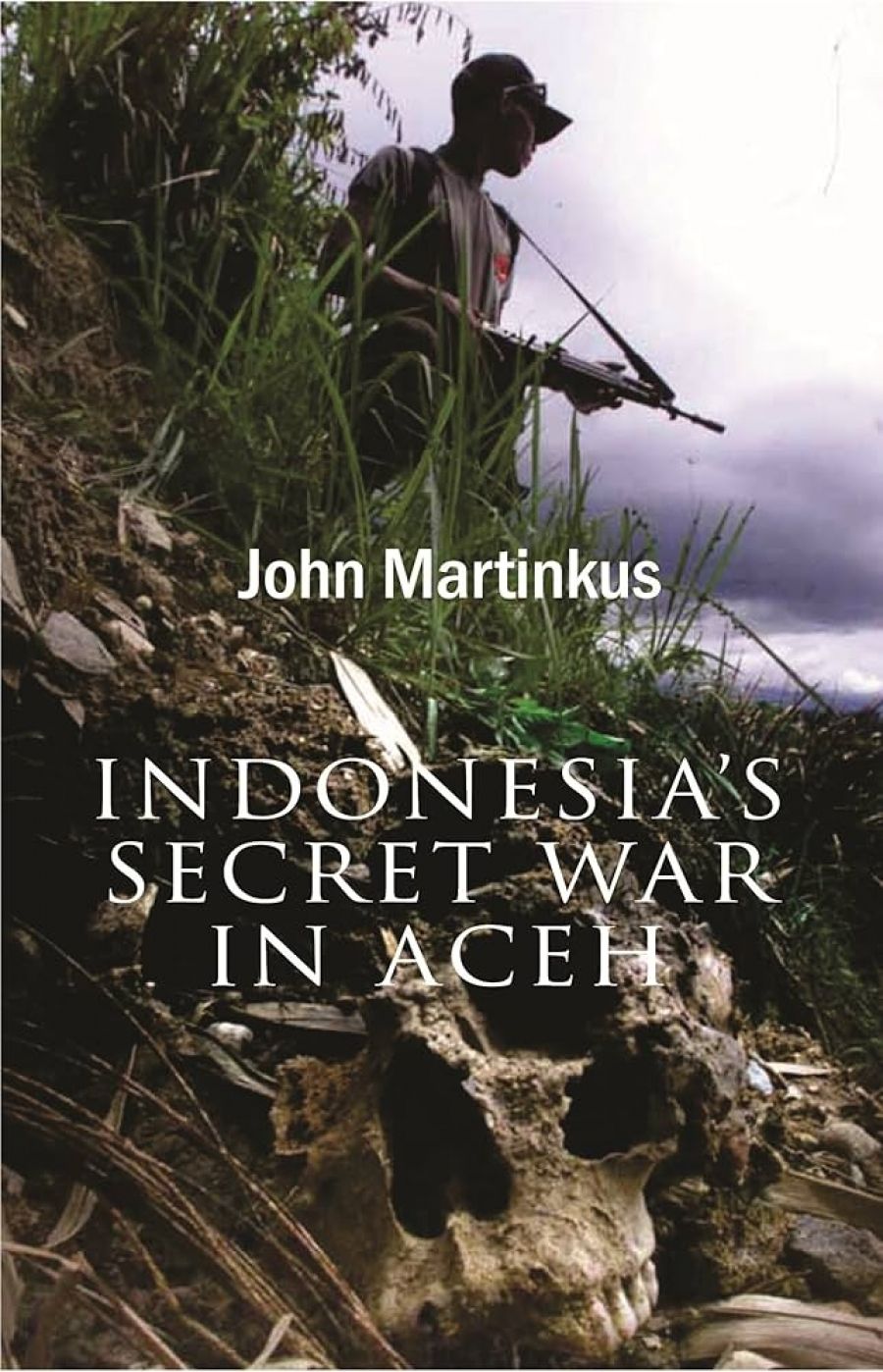

- Book 1 Title: Indonesia's Secret War in Aceh

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $32.95pb, 345pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

There seem to be two ways of looking at Indonesia these days. One is from the inside out, starting with Java and Jakarta and national politics, and then examining how national politics affect the trouble spots on the periphery. From this perspective, positive developments can loom large, such as democratisation, a much freer press and broader social discourse, and the direct election of a president for the first time in Indonesian history, although problems such as pervasively corrupt elite politics, environmental degradation and patchy economic growth arc also recognised. But at least there is some good news.

The other way is to start from the outside in, with trouble spots such as East Timor. and then proceed to other conflict areas such as Aceh, Papua and Ambon, where good news is hard to come by. This is the approach of John Martinkus, a crusading journalist who wrote about the East Timor crisis, then produced the present book after visiting Aceh at various times during 2001-2003, including the period when the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement (COHA) was signed. He travelled widely around the province, interviewed GAM and TNI leaders, and witnessed the period of moderate hope after the signing, which was followed by constant disillusion as the process stalled. From these experiences, it may be easy to conclude, as Martinkus does, that Indonesia is a ‘false state’. The story is a grim one, and not only because of the death toll. Once the peace process broke down, Martinkus reports there was a constant harassment of human rights workers and others who might have been useful mediators. The TNI, led in some cases by the same commanders who appeared in East Timor, used many of the techniques of intimidation, extortion and the use of militia that became familiar in the earlier crisis. The GAM emerge, as one might expect, as the heroes. (Were they really blameless?) One obscure aspect is exactly who the militia are; their personalities do not emerge with any clarity, unlike their counterparts in East Timor.

Perhaps unusually for a journalist, Martinkus acknowledges the importance of the historical background. It is indeed impossible to make sense of current developments without knowing of Aceh’s nineteenth-century independence, the long war by which the Dutch finally incorporated Aceh into the East Indies, Aceh’s strong support of the Indonesian Republic during the revolution against the Dutch, and regular dissension and even revolt since then, when central government promises of autonomy were not honoured.

A postscript takes the story up to May 2004, when martial law was replaced by ‘civil emergency status’. The main conclusions of human rights groups at that time were that the population had been terrorised, and that rapes and torture were regular occurrences. These reports underlined the central paradox of the TNI’s behaviour in Aceh and elsewhere: that their hardline defence of Indonesia’s unity has become the best argument for the country’s dissolution.

Nevertheless, if Aceh is to achieve independence and the ‘false state’ is to break up, much more needs to happen than might be inferred from this book. One aspect that is scarcely mentioned is the province’s international legal status. Not a single nation-state recognises Aceh’s claim to independence; even Muslim countries that might, at first glance, be sympathetic will not readily support the disintegration of another Muslim state. Martinkus criticises foreign governments, especially the US and Australia, for supporting Indonesia’s territorial integrity, but it is unclear what else they can do. Outside assistance, sympathy and support is thus much lower than in the case of East Timor. But if the present state of affairs persists, indefinite low-level insurgency, with constant deaths, atrocities and a disaffected population are all the province can look forward to. GAM does not seem strong enough to defeat the TNI, but the TNI have done such an appalling job of winning hearts and minds that they certainly cannot beat GAM. A crucial consideration, as in the case of East Timor, is the state of political will in Jakarta. The ‘inside out’ approach can be helpful in judging such factors.

The Aceh issue may have entered a fresh phase with the recent election of the new president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono. As a former general and with a strong popular mandate, SBY (as he is called) has the best chance in years of resolving the Aceh issue. Indeed, shortly after his election, he indicated that Aceh might need to be re-examined. With a death rate running at 120 per month this year, Aceh demands central government initiative, though the new president has many other urgent matters to attend to.

Alas, SBY gave a little real support to the earlier peace process, despite being a government minister with relevant responsibilities. Now the military seems to think it has the insurgency under control, so no further negotiations are necessary. In one sense, therefore, it may be even more difficult to restart the peace process, as this could look like a political setback for the TNI. Unfortunately, little in SBY’s record suggests that he is prepared to face off determined resistance by commanders on the spot, especially as some of his associates served in Aceh. But he now has the opportunity.

Comments powered by CComment