- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Letters

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hearts with One Purpose Alone

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

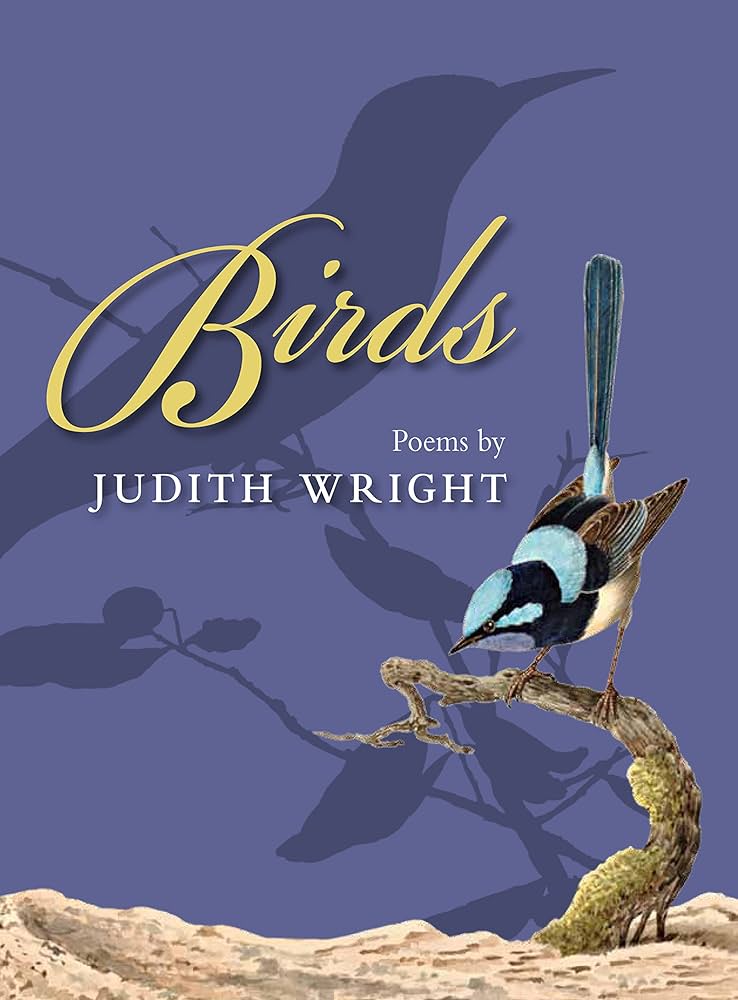

These two volumes are a credit to their publishers. The format of The Equal Heart and Mind, a new departure for UQP, is slightly smaller than the usual paperback. The pages are deckle-edged, and the cover, in brilliant tones of magenta and purple, has its edges folded in on themselves as if to enclose and protect the contents. Very effective! In the National Library production of Birds: Poems by Judith Wright, the poems are accompanied by pictures from the National Library of Australia’s Pictures Collection, many by colonial artists. Paintings such as J.W. Levin’s ‘Rainbow Bee-Eater’ (1838) and E.E. Gostclow’s ‘Black Cockatoo’ (1929) are rarely seen masterpieces. This edition is a collector’s piece, worth buying for the pictures alone. Let’s hope that these two books herald a renewal of interest in Wright and her work.

- Book 1 Title: The Equal Heart and Mind

- Book 1 Subtitle: Letters between Judith Wright and Jack McKinney

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $24.95 pb, 202 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Birds

- Book 2 Subtitle: Poems

- Book 2 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $24.95 pb, 80 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The Brisbane of The Equal Heart and Mind was a city in chaos. Transport and phone calls were difficult, and letters were often the only means of contact. Those between Judith Wright and Jack McKinney, written in 1945 and 1946, blaze their way from suburb to suburb, and later to and from ‘Quantum’, the primitive timber cottage they bought at Mount Tamborine. A subsequent group – written in 1950 when their daughter, Meredith, was born – is also included. The letters are interspersed with passages of commentary, poems and a selection of photographs. Patricia Clarke’s short introduction and Meredith McKinney’s ‘Memoir of Jack and Judith’ precede the letters, and the volume concludes with Wright’s poignant ‘Epilogue: Jack’s Death’ and the elegiac poem ‘The Vision’.

The most impressive feature of the letters is their many and continuous statements of love and commitment. As well, and almost by the way, they contain a mix of philosophical speculation, comments on books they are reading, anecdotes about contemporary literary figures, and details of the minutiae of daily life: ‘[Y]ou owe me three and eightpence’; I’m having eggs boiled on the spirit stove for my dinner this week.’ There’ an occasional acerbic comment, particularly in relation to Clem Christesen, seen by Judith as a ‘whining little beast’, to be trusted no more than ‘a snake under the house’. Judith and Jack were very annoyed with Christesen: he was prevaricating over the publication of Jack’s first manuscript, ‘Towards the Future’, and seems to have had too cavalier an attitude towards the contract for The Moving Image, Judith’s first volume of poetry.

There are interludes that set the mind spinning: Judith writes of carrying a Japanese skull around in a parcel: it’s been sent to the university, and she has to pick it up and deliver it. Why would the University of Queensland want or need a Japanese skull? On a happier occasion, she picnics in New Farm Park with Val Vallis, listening to César Franck on the gramophone to the astonishment of the ‘clockfaced citizens’ hurrying by. But neither cares. Judith is, she says, always odd, always an outsider. This is nowhere more evident than in her passionate love affair with McKinney, some twentythree years her senior, an almost penniless veteran of World War I living apart from his wife and grown-up family.

Judith was in her late twenties when she went to Brisbane to work for the Universities Commission and to help Christesen with the production of Meanjin. At Christesen’s house she met Jack, who was best known for his prize-winning novel Crucible (1935). The lovers faced a deeply conservative and censorious society. ‘[L]ooked at from this angle,’ she writes ‘you and I are queer and sinful fish!’ When she finally revealed their love affair to her father, he wept; not, I think, for the disgrace, but for her precarious situation. Their marriage would only become possible after a change in the Queensland laws in 1962 allowed Jack to divorce. However, her father provided a private nurse for Meredith’s birth in 1950 and paid for Judith’s convalescence at Lady Cilento’s Mothercraft Centre. He was, as always, deeply concerned for her health.

At the time covered by the letters, McKinney was obsessed with, and carefully formulating, a philosophical vision that would eventually lead to the publication of two books and a series of articles, most of them in prestigious overseas journals. They analyse the evolution of language since primitive times and the development, through language, of a common ‘world-picture’, one that was currently disintegrating. The build-up of violence and hatred in the twentieth century was, according to McKinney, a direct result of the loss of connection between feeling, language and the world ‘out there’. McKinney’s theory was no milk-and-water abstraction, but, he writes triumphantly, an ‘intellectual atomic bomb!’ If accepted, it could produce a ‘complete revolution of thought in one fell swoop’. It is, he writes, ‘the only thing that could defeat the physical a.b. [atomic bomb]’. Judith is equally passionate: ‘[W]hen my modest name goes down to posterity,’ she writes, ‘it will be because I had the honour of typing the first copies.’

The influence of their shared philosophy on the poetry is problematic. To many people, there is a basic incompatibility between the dry and dusty abstractions of philosophy and the passion and intensity of the lyric. Two poems, ‘The Moving Image’ and ‘Eli, Eli’, discussed in the letters as poetic expressions of Jack’s philosophy, are certainly not among Wright’s best. But later poems as ‘Naming the Stars’ and ‘Interplay’ demonstrate in apparently simple lyrics, a combination of philosophical thought and emotional power.

Other Australian women writers have risen to the same challenge. ‘Australie’ in the nineteenth century, and Gwen Harwood in the twentieth, are notable examples, but there are others. In fact I would suggest that there is a tradition of philosophical poetry, usually related to perceptions of the physical world, in women’s writing, and no one does it better than Judith Wright. Take, for instance, the last lines of ‘Interplay’: ‘Look how the stars’ bright chaos eddies in / to form our constellations. Flame by flame / answers the ordering image in the name. / World’s signed with words …’ Effortless simplicity. Perfection of language. Yet the poem dramatises the notion that the act of naming, of putting a human signature on the chaos of the outside world, was the original creative feat. It was, according to the poem, a human, not a divine, act.

This edition of Birds: Poems by Judith Wright is the first for twenty-one years. As Meredith McKinney comments in her introduction: ‘Reading this volume we experience a kind of wing flicker – from light and delighting, to darker tones. and back to light again.’ The poems are certainly not as simple as they first appear. Wright’s delight in each species, her acute observation of their appearance and habit, and the occasional humorous treatment are tempered, for this reader at least. There is an overall sense of the cruelty of the world of the birds, a condition that, according to the poem ‘Extinct Birds’, also belongs to us. It ‘rhymes with us’. The inclusion of six extra bird poems from throughout Wright’s work, including the magnificent ‘Camping at Split Rock’ and ‘Lament for Passenger Pigeons’, adds a further dimension. The latter is her most significant conservation poem, and both of them take us back to the philosophical discussion – of the relationship between love, language and the natural world – that so concerned the letters of The Equal Heart and Mind.

Comments powered by CComment