- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Journals

- Custom Article Title: Maria Takolander reviews 4 Literary Journals

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Dogs of Literature

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In ‘Ouah, Ouah’, a poem in the current issue of Island, Chris Wallace-Crabbe writes: ‘Dogs go shadowing our lives like history, / furbags of the quotidian.’ Literary journals are like that in some ways. Island, Heat, Conversations and Overland undoubtedly aspire to being more than alley mutts or underarm accessories. Indeed, they attest to the increased seriousness and politicisation of Australian literature. Like dogs, these journals shadow history. Like dogs, they also live in the shadows, lingering at the sliding door, waiting to be asked in; and they’ve evolved in different ways to achieve that aim.

- Book 1 Title: Heat 7

- Book 1 Subtitle: Bedtime Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: $24.95 pb, 256 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

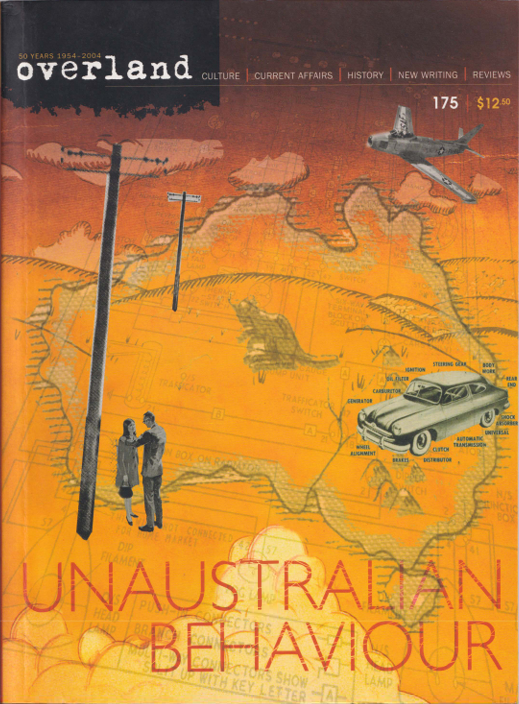

- Book 2 Title: Overland

- Book 2 Subtitle: UnAustralian behaviour, no. 175

- Book 2 Biblio: $12.50 pb, 112 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Winter Conversations

- Book 3 Subtitle: Volume 5, number 1

- Book 3 Biblio: $18 pb, 79 pp

Ivor Indyk’s Heat stands out: thick, muscular, dangerous, beautiful. Its pieces are unafraid; its range is expansive. It carries Australian literature out of the darkness and cold. It is the Alaskan Malamute of literary journals.

The prose is impressive. Among my favourites is Joanne Kujawa’s ‘Dreaming Havana’. The story is told by Havana, the Hispanic seductress rescued from Western stereotype, who tries to lure a would-be Western biographer of Che Guevara closer to the magical historical truth. The narrative strategy is risky, but Kujawa pulls it off. She also manages to pay cringe-less tribute to Castro’s and Guevara’s bravura: ‘A few idealistic men in borrowed jackets crossed the sea from Mexico to Cuba on a boat called “Granma” and changed history … This is the only lesson worth learning from history.’ It is the marvellous history lesson that the Western biographer cannot see.

Other highlights in prose include Rikki Ducornet’s reflections on a novel in progress. set in Algeria. She writes of the ‘hot bones and breath· of the Arabic language, with vowels ‘that like snakes bite their own tails’. Ducornet’s language is as striking as its subject. Her evocation of torture by, and resistance to, the French occupation is disturbing and uplifting. She writes of the torture by electric wire of a man that ‘had left a kind of indigo script at the comers of his nostrils, his mouth and eyes, and in the delicate hollows beneath his ears. His dignity, he claimed, was recovered at the moment of his country’s independence.’ Ducornet admits that she was only ever a visitor to Algeria but asserts ‘a 40 years haunting demands, at the very least, a leap of faith and mind’. It is justification enough.

Peter Raftos’s Careyesque anti-capitalist parable ‘Quark’ is also memorable. Raftos comments on the unsustainability of capitalism, of a commodity culture that must consume everything, in a story that is as mesmerising as the subatomic particle that his protagonists buy as the centrepiece for their living room. It ultimately sucks up the world.

The poetry is as strong as the prose. Heat opens with some final poems by Bruce Beaver, starting with ‘Something for the Birds’, which begins: ‘Two muezzin magpies from pine minarets / call up the sun and every worshipper / of it and every Allah in this world / and past it to the very stars and planets.’ The poem sets up the internationalist and political flavour of this edition, but it also suggests the journal’s reach, its encompassment.

Heat is confident enough to include not only the contemporary and the traditional but also the newborn, dedicating a section to the would-be avant-garde Neopulp movement, which includes a manifesto and some examples of writing. Neopulp-ists claim to be making ‘outrageous statements’ about the virtues of schlock. However, B-grade has always been self-pastiche that offers possibilities. L. Ron Hubbard and Quentin Tarantino recognised this long ago.

Heat is also secure enough to have a segment dedicated to ‘Literary Engagements’, in which Brian Castro makes some ‘outrageous claims’ of his own. He argues that the trick to great writing is to ‘border on boredom’ so that time ‘is carved out for thinking the normally unthinkable’. The suggestion is enigmatic. However, Heat proves the contrary: literature doesn’t have to be monotonous to inspire the meditative.

Conversations isn’t unengaging, but there’s something peculiar about it. It’s neat, flashy, and correct in its politics. Its cover features a photograph from a fashion show – appositely, for me, as this is the Dalmatian of literary magazines.

The journal does offer entertaining titbits. The autobiographical piece by one of the journal’s editors, Brij V. Lal, is appealing. Upon hearing of the death of his schoolteacher on Indo-Fijian radio, Lal reflects upon the wisdom of a man who taught his students that the sun never set on the British Empire ‘because God does not trust an Englishman in the dark’. The students called their teacher ‘Chandula Munda’, which translates, fascinatingly, into ‘Baldie Baldie’. However, Virginia Wallace-Crabbe’s photographs of a prêt-a-porter parade outshine all else, proving the unassailable allure of glamour. Robin Wallace-Crabbe’s story of the shoot is another highlight. He relates how, in this world of the tall, beautiful and immaculately dressed, a short, fat man in a tight suit protests: ‘Shame! Animals!’ People assume he is famous, for surely ‘no non-celebrity would dare kick up such a fuss?’

Island is less glamorous and mysterious. It wears its green politics on its sleeve and is content to stay at home, although it will watch birds through the living-room window. It’s a bloodhound.

The issue begins with an interview with Bob Brown by the editor, David Owen. This is followed by an interesting article by Peter Timms on wilderness photography, its romanticisation and romanticism, its artistic conservatism and efficacy as propaganda, and its potential for the new. Then there are three essays on wilderness trails which are as unadventurous as wilderness art. Coming across Vivienne Ulman’s intensely personal essay was an engaging shock.

The poetry is the journal’s strength, seen in Michael Farrell’s ‘Sunflower contest’ and Chris Wallace-Crabbe’s ‘Ouah, Ouah’, although Natasha Cica ‘s review of non-fiction books that deal with political issues she describes as ‘barbeque stoppers’ also grabbed my attention. These books ask questions ‘that probe more deeply than pondering Mark Latham’s “manboobs”, Steve Irwin’s peculiar sense of the humorous media stunt, or other ephemeral fluff in the national navel’.

Overland aggressively pursues such party-pooping aims. It is parochial, socialist and anti-aesthetic. It’s the pit bull of literary journals.

This edition sniffs out the concept of ‘UnAustralian behaviour’. In a nice piece of sophistry, Nathan Hollier argues in his editorial that real Australians are the marginalised ones who remain immune to John Howard and American influence. They’re also the contributors to and readers of the journal.

As with Playboy, one reads Overland for the articles. Katherine Wilson exposes a pro-GM media campaign, which is sponsored by GM food companies and labels opposition to their hard ‘science’ ‘green mysticism’. Tony Birch points out the hypocrisy in media concerns about Aboriginal violence towards White Australia. Maria Tumarkin does a similar job, exposing double standards about Australian ‘traumascapes’, contrasting respect for ‘white’ war sites with disrespect for Aboriginal sacred sites. The essays, however, seem constrained by their prescribed length.

This edition is also interesting for poetry editor John Leonard’s defence of his controversial tastes. He asserts that personal poetry is as interesting to him as holiday snaps. A hard man to please, he also criticises the anti-Bush poetry of Jennifer Maiden, featured in Heat, for not going far enough. However, the poetry in Overland is neither uniformly political nor particularly satisfying. In fact, something about the prescriptiveness of the journal’s literary editorship generally inspires cynicism. I found myself thinking, for example, that one of the fiction pieces has it all: a message of tolerance of cultural difference, a feminist agenda. Aboriginal protagonists and a reference to Penang.

Overland stirs old problems. These are serious times. However, as Heat shows, serious literature need not renounce the literary. And even Leonard likes Chris Wallace-Crabbe, which goes to show that if you do it well, you get away with it, like a dog with a bone.

Comments powered by CComment