- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Natural History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Collectors and Improvers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In this well-designed volume of essays, Paul Fox introduces the reader to the world of nineteenth-century botanist, nurseryman and collector (professional, commercial and amateur) and to the ways in which six men, their patrons and rivals reworked the Australian landscape. Settlement changed the landscape at a time when the boundaries of the botanical world were constantly enlarged by the discovery of plants from Asia, the Pacific, the Americas and Australasia. Botanists followed the imperial flag, British botanists (led by Sir William Hooker) eagerly incorporated the new finds, and the appetite of a growing race of collectors was met by energetic nurserymen who combed the world for exotic plants.

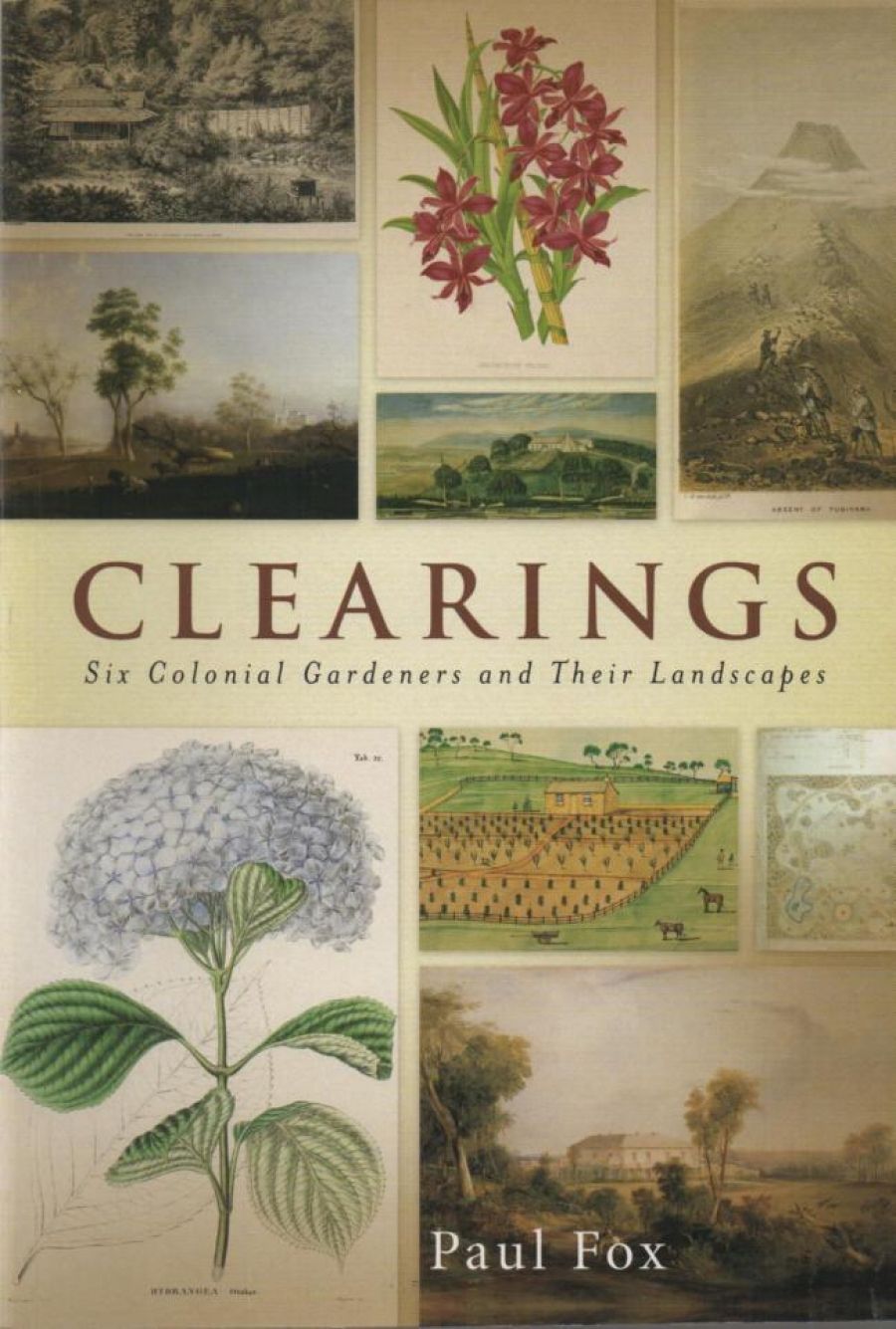

- Book 1 Title: Clearings

- Book 1 Subtitle: Six colonial gardens and their landscapes

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $59.95 hb, 286 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The opening essay, on the relationship between Sir William Macarthur of Camden Park, gardener and collector, and the London firm of nurserymen, Veitch and Son, serves as an introduction to the intercontinental aspects of botanising and provides a platform from which Fox can criticise the imperial aspects of botany, the desire of Hooker and fellow professionals to control and regularise taxonomy, and the ambitions of Veitch and others to monopolise new discoveries. The following essays, set in Victoria, house a profusion of themes, starting with the import and acclimatisation of exotic plants by such men as Thomas Lang, the Ballarat nurseryman, reputed to have brought a million trees, shrubs and vegetables to Victoria; and the forester William Ferguson, who specialised in the ornamental planting of trees. A corollary of this was the domestication in Victoria of trees (such as Moreton Bay Fig, Bunya Bunya and Palm) from Queensland and New South Wales by William Guilfoyle.

Guilfoyle embarked upon the next step, the transformation of the Melbourne Botanic Garden into a picturesque landscape, combining the English tradition (only lightly sketched) with his observations of tropical paradises in the South Seas. These were elaborated in a series of private gardens and in the Warrnambool Botanic Garden.

Thomas Lang and Josiah Mitchell looked beyond the ornamental. To them, gardens were a sign of moral improvement and social progress, a means by which colonists could assert their independence and feed themselves. Both men were attracted to practical problems. Lang cultivated the Majetic apple stock, which proved resistant to the American apple blight, and promoted the planting of shelter belts to protect stock. Mitchell advocated programmes to reverse soil exhaustion, realising that Victoria had only a limited amount of arable land. Moving from gardening proper into agriculture, he became a critic of the Selection Acts, arguing that small blocks led to the destruction of land. He urged fanners to pool practical knowledge through the medium of the press.

Grazing transformed the land. John Robertson of Wando Vale noted the destruction of native grasses in the Western District, the spread of silk grass and the beginnings of erosion. Diggers stripped mining districts of their trees. Selectors cleared land for farming. Redgums in the Barmah Forest were cut down for railway sleepers. Even botanists had an ambiguous record. Ferdinand von Mueller (who deserves an essay in his own right) was blamed for the introduction of the cape weed. Guilfoyle removed most of the eucalypts in the Botanical Gardens. It was the least formally trained of the six men, Daniel Bunce, who displayed the greatest sympathy for the native flora. Ferguson, like Mitchell, deplored the land clearances that led to degradation, and he suggested the most extreme solution: the original forests (since destroyed) must be replaced with exotic trees. Fox devotes the final essay to Ferguson, whom he calls the man who could not see, even when examining the riches of the Otway Forest. Ferguson, it is implied, was both the culmination of a century of gardening and a pointer to one future development (he was appointed the first inspector of Forests).

In his all too brief introduction, Fox states that there was a diversity of practice and understanding, not one ruling orthdoxy. Rivalries abounded, especially between commercial nurserymen and directors of botanical gardeners, and between scientific botanists and landscape designers. Von Mueller’s disagreements with Guilfoyle, Mitchell and Ferguson enliven the essays: all were men with strong views. all sharing the determination and enthusiasm that were characteristic of much of the nineteenth century in general, and of the botanical world in particular. An epilogue, bringing together all the themes touched upon in the essays, would have been welcome. Instead, the final essay (on Ferguson) concludes with a question – ‘how do we inhabit the clearings created by a century of this kind of seeing?’

These short essays, aptly illustrated, whet the appetite for a general history of nineteenth-century gardening and landscaping in Australia, incorporating all the research that the study of garden history (itself a recent development) has produced over the last twenty-five years.

Comments powered by CComment