- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hazy Profiles

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This, of course, is literary Archibald Prize and, just like the art competition that annually sets Sydney’s cognoscenti abuzz, it will provide grist for plenty of arguments. Which of these profiles catches a passably good likeness of its subject? In which are the brush-strokes boldest and most compelling?

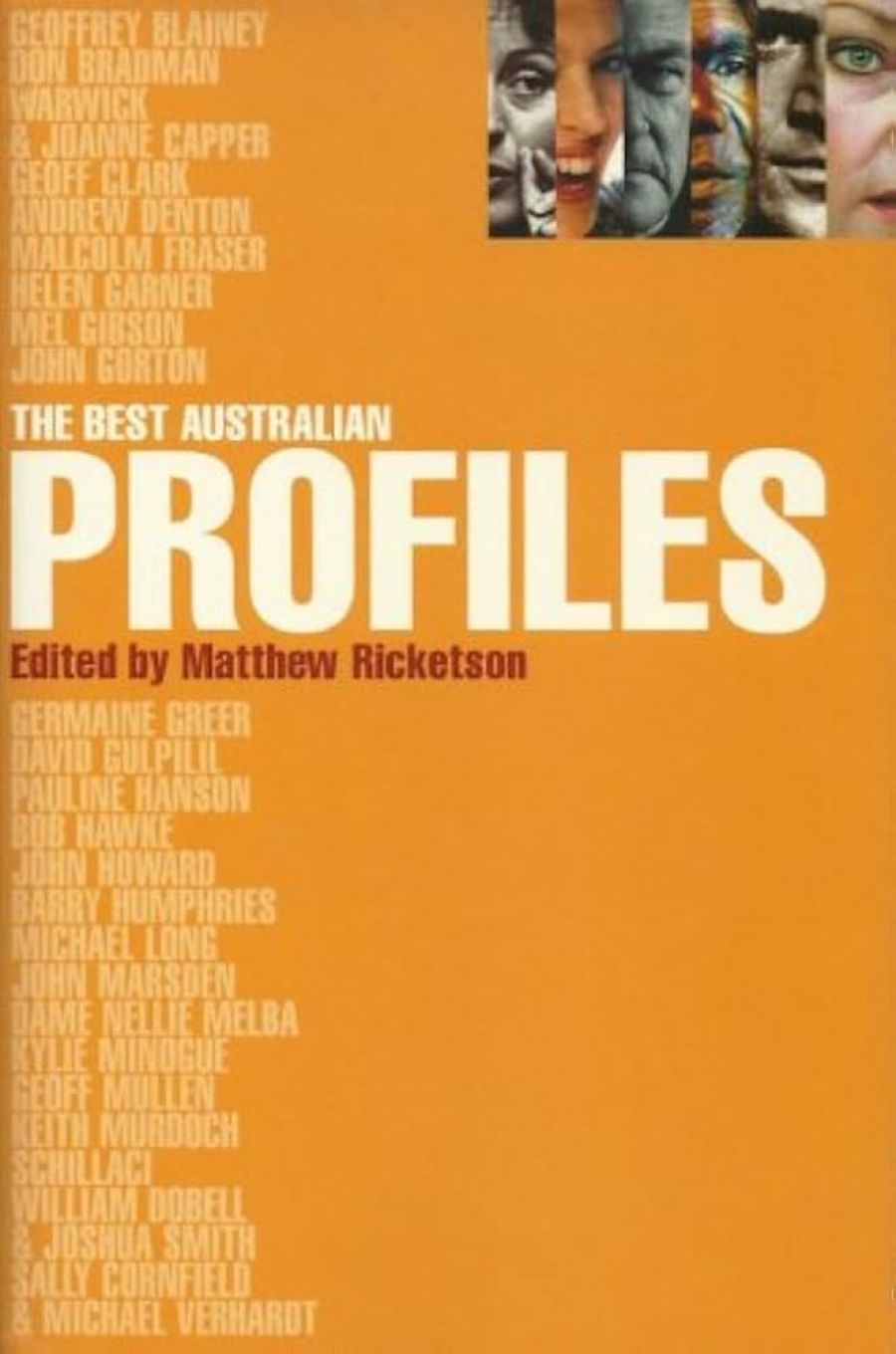

- Book 1 Title: The Best Australian Profiles

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $29.95 pb, 371 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

He begins with the notion that a profile is a mini-biography: ‘Profile-writers tell us what the Famous Person is like to be with – how they look, dress, speak, behave, at work or home, with friends, family and colleagues.’ He later indicates that profiles are ‘character sketches, pen portraits or brief lives’. On this basis, less than half the pieces he has selected are in fact profiles. John Birmingham, for example, contributes one of his typically rambunctious pieces, allegedly a profile of Pauline Hanson, but in truth a profile of Ipswich, the provincial city that provided the cradle for both the profiler and profilee. He appears never to have met Hanson, and manages only to fire an impertinent question at her from a media scrum, to which she replies enigmatically: ‘I’m not here to answer those sorts of questions today!’ It is beautifully done, but we learn almost nothing about Hanson while gaining genuine insights into how it was that the Darling Downs hinterland thrust her into the political limelight. Similarly, Janet Hawley purports to profile ‘William Dobell and Joshua Smith’, but instead tells the fascinating story of the long fallout from Dobell’s most famous painting. Paul Toohey’s ‘profile’ of Malcolm Fraser is the rollicking talc of his Memphis misadventure: and Les Carlyon provides a typically brilliant sketch of the racehorse Schillaci, without conveying to me why exactly this animal is so special.

Nevertheless. a number of profiles do offer significant insights into what makes their . sitters tick. Although David Marr’s sketch of John Howard focuses single-mindedly on the prime minister’s attitude to Aborigines, Marr identifies the essence of the subject. Here is the ‘skinny kid with a quick tongue and a hearing aid’, from the devoutly Methodist family that didn’t mix (‘teetotal, stand-offish and proud’), grown to manhood. Frank Robson’s John Marsden, and Antonella Garnbotto’s Warwick and Joanne Capper, are like brilliant polaroids: they vividly capture their subjects at their apogee, and in both cases leave us cringing. But they fail to explain adequately how these people came to attain such meretricious fame. By comparison, Hetherington’s classic profile of Keith Murdoch – admittedly a longer piece – convincingly evokes this significant historical figure who was, in his day, as ruthless and manipulative as his son was to become.

Clearly, length is important. By far the most extended portrait in this gallery is that of Barry Humphries, by the American writer and critic John Lahr. Originally published in The New Yorker, it is magnificent and insightful. It almost pre-empts the great comic’s own various published attempts at autobiography.

The conversation between Margaret Simons and Helen Garner is definitely not a profile of the latter. Garner explores, with that unflinching honesty that is her trademark, the act of betrayal inherent in so much good journalism, and particularly in interviews and sketch writing. Simons observes Platonically: ‘I mean, you can’t write things without the people you write about feeling betrayed. When I write this up, there may well be things that will make you wince.’ To which Garner responds Socratically: ‘The really interesting thing is why does one flinch? What exactly is the betrayal we are talking about and what are the things that make one flinch? It seems to me that it’s not so much the revelation of fact, as the feeling that somebody else is telling your story, and stating something without the justifying tone that you use yourself.’

In the end, perhaps, it matters little that many of these pieces are not profiles, nor that two of them are not by Australians and some subjects are not technically Australian. There are some wonderful profiles, including David Leser’s Andrew Denton and Mungo MacCallum’s John Gorton. Better still, there is some brilliant journalism, including Jon Casimir’s fabulous list of a dozen reasons for Kylie’s unlikely success and Peter J. Boyer’s account of the controversy over Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ. Indeed, by far the most poignant and thought-provoking contribution is not within cooee of being a profile. It is Garry Linnell’s compelling story of the birth of a pair of premature boys to a young couple from rural Victoria, and what happened afterwards to both the twins and their bewildered parents.

At the risk of sounding pedantic, I have to mention that the text suffers from spectacularly sloppy editing and proofreading, even by lax modem standards. This has a wildly disorientating effect. Thus Warwick Capper is described as a former ‘boilermaker’ who at one stage ‘misused’ his wife (possibly true, but the author probably intended boilermaker and missed). Worse, highlighted as No. 4 on Jon Casimir’s list of Kylie’s virtues is, puzzlingly, ‘Kylie really can’t act’ (I double-checked via Google that the negative is an error).

Ill-served as he may be, Ricketson is to be congratulated on a highly readable anthology, even if we are left none the wiser as to what he imagines a profile actually is.

Comments powered by CComment