- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: A Life Surveyed

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Life Surveyed

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Of the two groups who opened up Australia to settlement, the squatters have created about their persons a huge library, both admiring and critical. The surveyors, who followed in their footsteps, have rarely captured the imagination (with the exception of Sir Thomas Mitchell and Colonel Light) but their influence, especially in metropolitan Australia, has been incalculable. The site of Melbourne was chosen by a governor, but it was surveyors who laid out the grid plan of the square mile, imposing it on a hilly site, bounded by a narrow river to the south and swamps to the west. Principal among the Melbourne and Port Phillip surveyors was Robert Hoddle, who ended a long career as the first Surveyor-General of Victoria (1851–53).

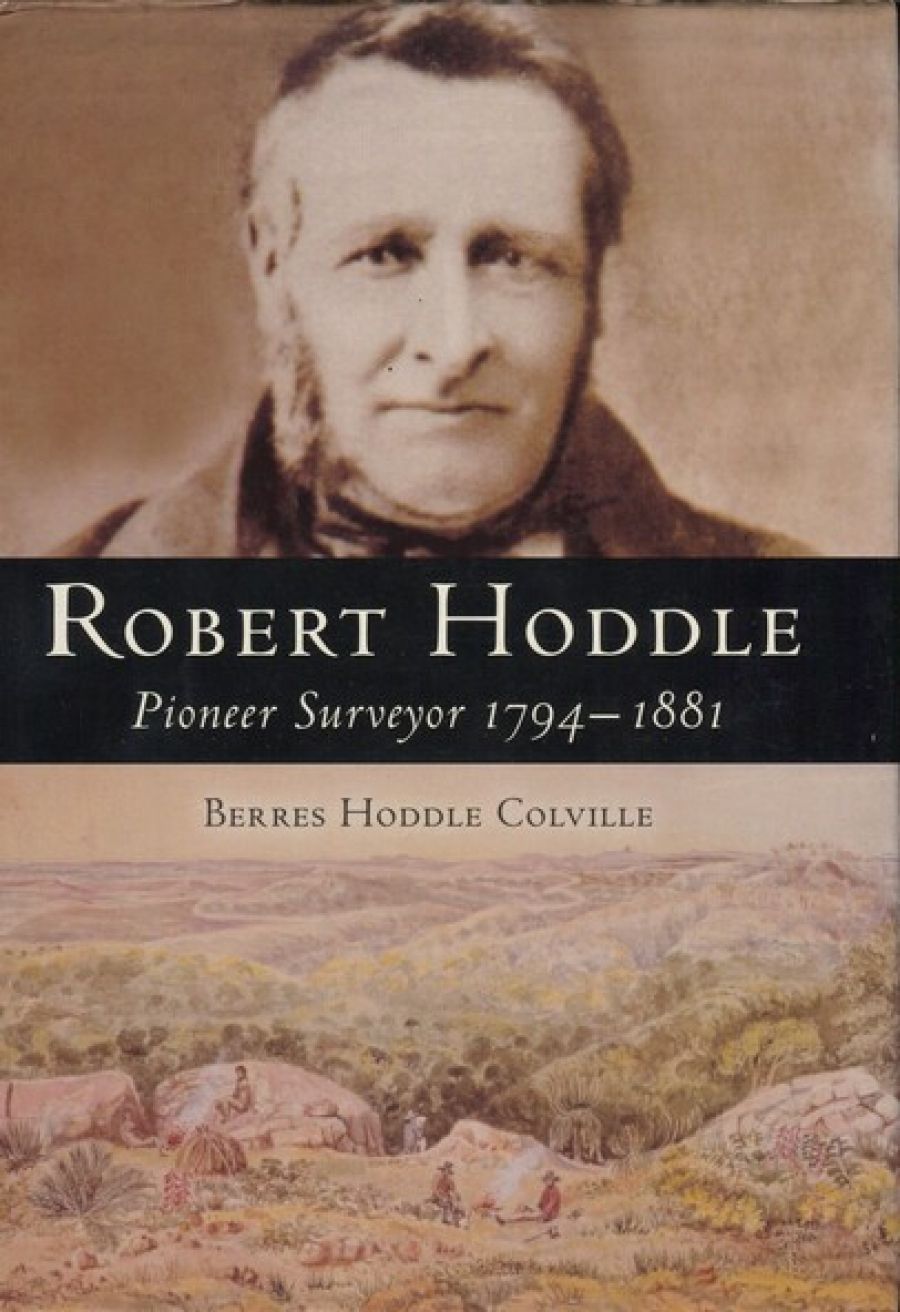

- Book 1 Title: Robert Hoddle

- Book 1 Subtitle: Pioneer Surveyor, 1794-1881

- Book 1 Biblio: Research Publications, $79 hb, 324 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Armed with the usual letter of introduction, Hoddle left for Sydney where he was to spend some fourteen years. The work was arduous and often disagreeable; equipment and rations were poor; the workmen unreliable. Aborigines and bushrangers presented constant danger. In a land-hungry colony, the pressure on surveyors (always understaffed) was intense. Oxley, his first superior, was inefficient; Mitchell, his successor, was demanding and peremptory.

Berres Hoddle Colville gives a detailed account of Hoddle’s work in the Blue Mountains, Moreton Bay (Brisbane), the Liverpool Plains, the Limestone Plains and the future Canberra, the Hawkesbury District, the Southern Highlands, Melbourne and its environs, and other parts of Port Phillip, as well as his English and Cape Colony surveys. The bare list of names indicates the ground covered by Hoddle, and it is no surprise to learn that he was hard-working and efficient, and that he ruined his health in the discharge of his duty.

Hoddle’s observations were not limited to topography. With an unromantic eye and lapidary style, he noted Aboriginal customs, Melbourne society and fellow surveyors. Such comments enliven otherwise dour field notes. Of most interest to Melbourne historians are his reflections on the planning of the town, the width of its streets, its water supply, and other matters that have preoccupied generations of the city’s inhabitants.

Hoddle retired, against his will, to make way for a younger man. In his Bourke Street house with its garden and cow paddock, he studied his books and sketches, housed in his library and gallery. Hoddle’s daily routine of the mind illustrates the tastes of that quiet middle-class Melbourne society so long ignored by radical historians – who, equally, may not care for his pragmatic views on the world about him.

Behind this workmanlike biography lies the shadowy outline of another life, one familiar to those students of nineteenth-century colonists and of novels of the period: a world of missing diaries and destroyed papers; a (perhaps unhappy) first marriage; an unexplained quarrel with his sister in New South Wales; a court case celebrated in its day; a second marriage to a woman forty-eight years his junior, and its painful dénouement. A withdrawn man, Hoddle had slowly accumulated considerable property in some eleven areas. His grandson, Robert White, took him to court in 1880, over the ownership of land in Elizabeth Street, which had passed into the control of the second wife’s family. At his death, Hoddle’s property was worth about £500,000. Three months after his demise, his young widow married a charming younger man, Richard Buckhurst Buxton (great-uncle of the historian Kathleen Fitzpatrick), who subsequently left her for the more sophisticated pleasures of London. The Hoddle estate dwindled away.

There are many questions the alert reader may ask, many oddities to be noticed. What happened to Hoddle’s diaries, which he wrote up every day, and which disappeared in obscure circumstances? How were relations between his first wife and his family? How curious that Hoddle should propose first to Blanche Baxter, then to her younger sister Fanny, who accepted him. How curious, too, that Buxton should court the elder Hoddle daughter first, before realising that Fanny, her mother, held the purse strings. What did happen to the Hoddle estate? And what sort of life did the aesthetic Buxton lead in London that it so puzzled his simpler relations when they visited him in his set of rooms?

Comments powered by CComment