- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: An Inscrutable Bond

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An Inscrutable Bond

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

For some Australians, the exotic, exciting and ultimately tragic relationship of Charmian Clift (1923–69) and George Johnston (1912–70) has attained the mythical status of other famous literary couples of the twentieth century: F. Scott and Zelda, Virginia and Leonard, Ted and Sylvia. The combination of beautiful people, prolific and personal writing, illness and suicide makes them irresistible and seemingly inexhaustible subjects for biographers and readers alike. In the case of the Johnstons, escape to London from the conservative Australia of the 1950s, and then years on the Greek islands of Kalymnos and Hydra, add another level of fascination. The dream of an idyllic island life is a resilient one: evidence that it is unattainable only serves to strengthen the myth.

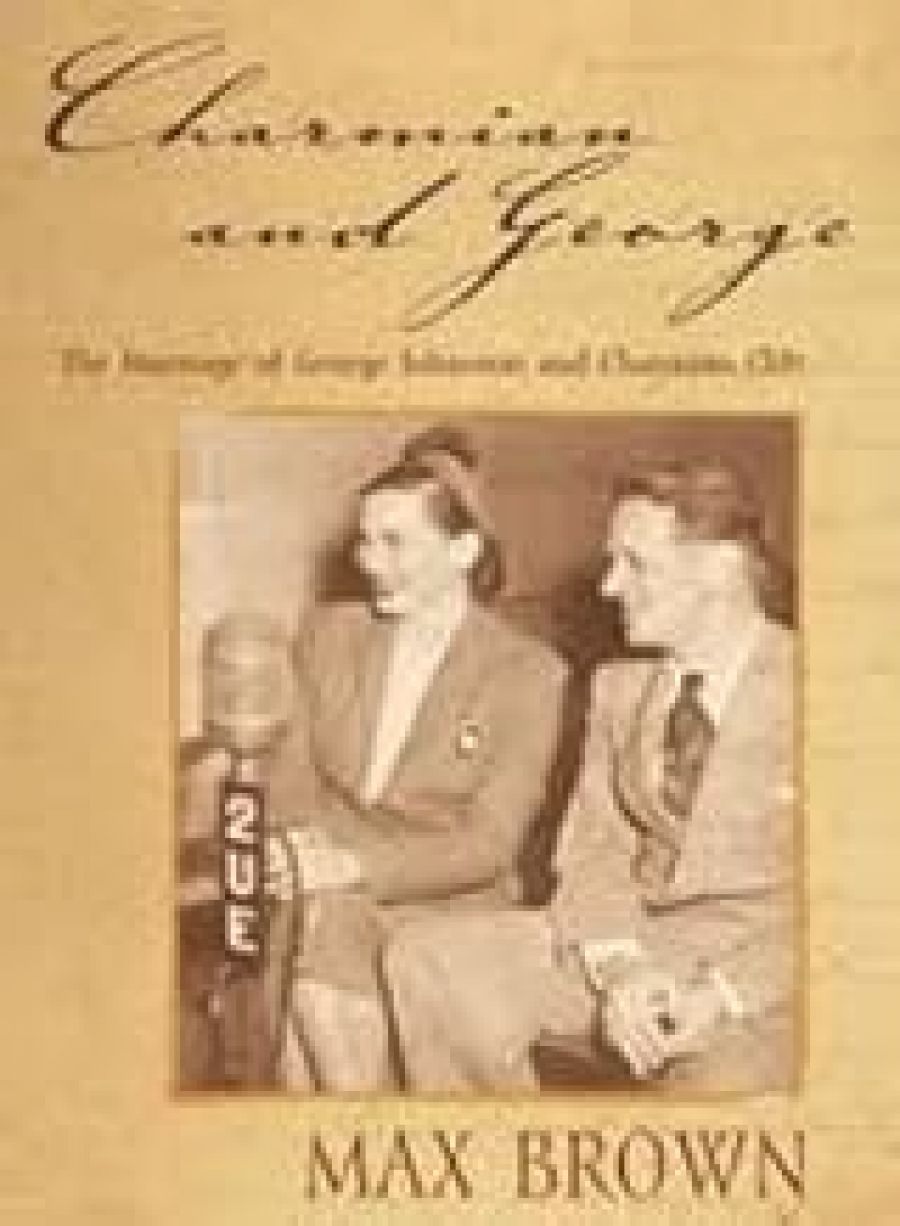

- Book 1 Title: Charmian and George

- Book 1 Subtitle: The marriage of George Johnson and Charmian Clift

- Book 1 Biblio: Rosenberg, $29.95 pb, 255 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Charmian and George is the result of twenty years’ research by journalist Max Brown, a colleague of Johnston’s at Melbourne’s Argus in the 1940s. That newspaper office was the setting for the meeting in 1945 of Johnston, a former war correspondent, and Clift, a beautiful young typist-reporter from Kiama. The scandal of their affair (Johnston was married) resulted in Clift’s sacking and Johnston’s resignation. It was a stormy beginning to what was to be a tempestuous marriage and an extraordinary writing collaboration, which got off to a flying start with the Sydney Morning Herald literature prize for their novel High Valley in 1948.

Brown was a journalist, and his style is the racy reportage of a bygone era. This is, however, backed by a prodigious amount of newspaper and archival research, a wealth of interviews and wide reading. He is also an astute analyst of the complex pot-pourri of fact and fiction that makes up the prolific output of the two writers. The result makes for fascinating reading.

Brown claims his book is, unlike the biographies by Garry Kinnane and Nadia Wheatley, ‘not primarily an academic work’. Accordingly, he does not verify friends’ and colleagues’ recollections in the way an academic biographer must, but he does place side by side the varied and often quite contrary opinions on his subjects and their relationship. Although a shrewd commentator, he is not narrowly judgmental about their complex lives; readers are offered a wealth of material from which to make their own assessments. There are many gems, such as Cynthia Nolan’s withering description of the boozy night sessions at the cafes on Hydra’s waterfront where expatriate writers pass around their work for comment and ‘each in turn says Wonderful out of one side of their mouth and Crap out the other’.

We gain insights into Johnston and Clift’s marriage, how in spite of the late-night partying and drinking, both writers were invariably at their typewriters the next morning. Though their parents only spoke enough Greek to get by, the Johnston children became imbued in the island culture. Martin, the scholar, read Thucydides and also became Sophia Loren’s interpreter when Boy on a Dolphin was filmed on the island; Shane, the most conservative of the siblings, was drawn to the ritual of the Greek Orthodox faith; and Jason, who was born on the island, spoke Greek as his first language. A tragic legacy of the Johnston story is the early deaths of Martin and Shane, but in this book we are offered a sense of the richness, as well as the pitfalls, of an expatriate childhood.

The author states that Charmian and George is about a marriage, but that ‘it also explores and challenges the myth of greatness surrounding the late George H. Johnston’. In the final section of the book, ‘The Reckoning’, Brown blames Johnston for Clift’s suicide in 1969 at the age of forty-six, just before the publication of the second volume of his My Brother Jack trilogy, Clean Straw for Nothing, which explores the illicit affairs of a woman recognisably based on his wife. Brown reads the third volume, A Cartload of Clay (incomplete at the time of Johnston’s death from the effects of tuberculosis in 1970), which concentrates on the suicide of Cressida, as ‘calculated to allay the suspicion that he had contributed to cause of death’.

It has already been suggested that Brown paints too glowing a portrait of Clift at Johnston’s expense, but this is clearly a book written by a man of his times – a journalist who was part of that very male world, who is imbued with its view of women, but who tries hard to bring Clift the writer out from the shadow of her more famous husband. He is at his least successful when he speaks for Charmian, when some of his underlying cultural prejudices about women surface. Of her suicide he remarks: ‘No doubt Charmian had regrets on many scores … but it was George about whom she felt guilty. It was bad enough to have uprooted him from Sydney and London, bad enough to have overworked him, bad enough to have tortured him with jealousy, devastating to think he lacked a sense of humour and could forgive nothing.’

Elsewhere, more pertinently, he quotes a wonderful passage from Clift’s notebooks that seems to sum up the dynamics of a marriage like hers and George Johnston’s:

They had a curiously exhausting effect on each other; neither knew why … Some inscrutable bond held them together. But it was a strange vibration of the nerves rather than of the blood, a nervous attachment rather than a sexual passion. Each was curiously under the domination of the other.

Comments powered by CComment