- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Custom Article Title: Creeping Emptiness

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Creeping Emptiness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Charles Edwin Woodrow Bean was born in Bathurst, New South Wales, in 1879, but his family moved to England ten years later. Bean returned to Australia in 1904 and became a junior reporter on the Sydney Morning Herald. On assignment in western New South Wales to produce a series of articles on the wool industry, Bean decided that the most important part of the industry was the men on whose labour it depended. He collected these articles in On the Wool Track, published in 1910. Bean’s monument is his official history of Australia in World War I, which can be – and has been – interpreted as an exegesis of his famous sentence: ‘it was on 25th April, 1915, that the consciousness of Australian nationhood was born’. But the earlier On the Wool Track is an Australian classic, also: an elegant memorial of a vanished pastoral age.

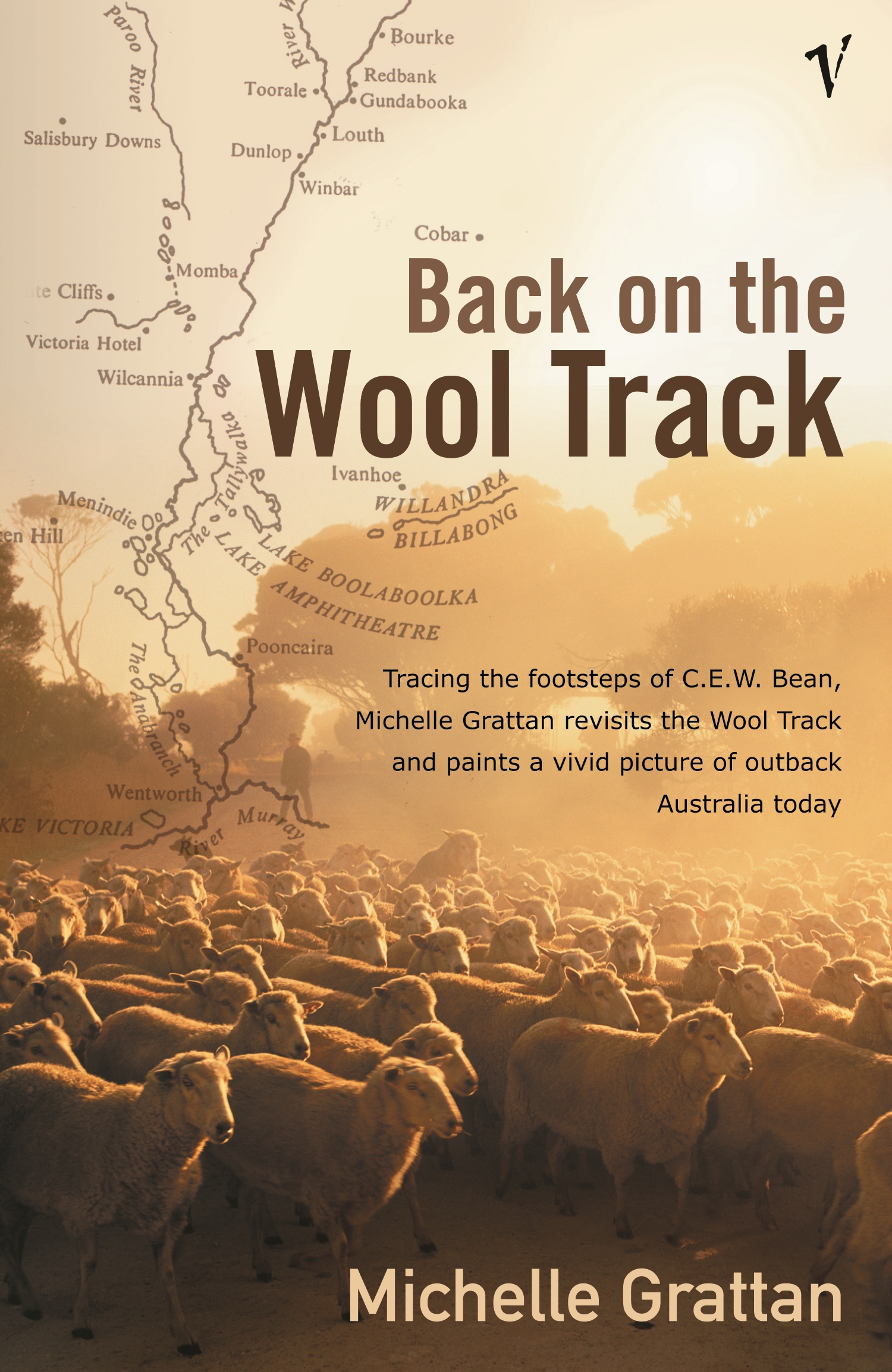

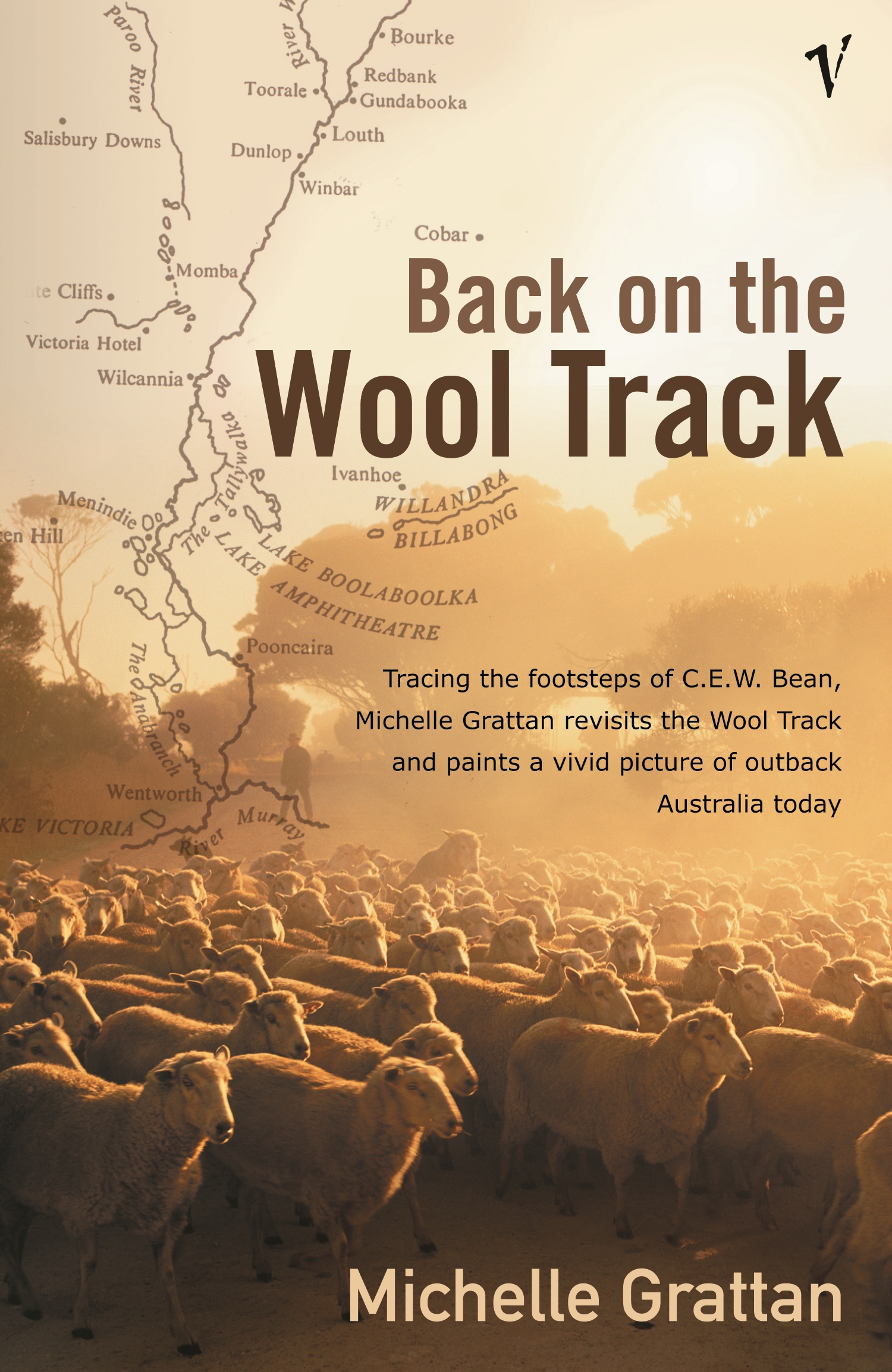

- Book 1 Title: Back on the Wool Track

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $24.95 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Only the very few are ‘not of an age but for all time’, and journalists are not among those few because their task is to be utterly of their time. In a sense, the better the journalist, the more historically locatable he or she will be. This is not to say that a journalist’s writing may not endure, but the value of journalism resides largely in the accuracy with which it reflects its time; that is, it has an historical value.

Bean was very much of his time – the title of his 1909 articles, ‘The Impressions of a New Chum’, illustrates the point – but he possessed timeless journalistic gifts: an eye for the telling detail and the illuminating incident; a capacity to create human interest and to choose the arresting quotation. Grattan quotes often, and often at length, from On the Wool Track, and her book is the better for it.

In her own voice, Grattan seems powerless to evoke anything. ‘The garden is full of fruit trees’ and ‘The grand London Bank building, constructed in 1888, was in its heyday in the early 1900s’ are typical sentences. There are bad sentences, too, containing ‘different to’ and ‘two thirds of what it was’. There is cliché: ‘A century later television, radio, email and internet have brought the global village even to the endless outback, albeit not as quickly or extensively as to city-dwellers.’

What all this illustrates, I think, is the difference between reportage and journalism, and what can happen when the two are confused. The sentences about the garden and about the bank are inventory rather than description: reportage, in other words. The colloquial constructions belong to a chatty style of writing that might be suitable for a light column. The clichés are the stuff of an opinion piece. In seeking to escape the conventions of her political correspondence, Grattan appears to have mixed them with other modes of newspaper writing, none of which is appropriate to her expressed intention, and the result is unhappy.

In his Wings of the Kite-Hawk (2003), Nicolas Rothwell presented an intense, richly referential account of the Australian outback, marred only by the narrator’s disinclination to reveal anything of himself. I was reminded of that book while reading this one: different though they are, there is a feeling of the same reticence. Why, at this stage of her highly successful Canberra career, should Grattan feel moved to journey to the outback and to write about it? Why, in the curious prologue to Back on the Wool Track, does she pose the following questions about Bean: ‘Was the still-young journalist dreaming of a famous future? Did the words come easily or with difficulty?’

These rhetorical questions belong to yet another style of writing, one that was popular at the turn of the nineteenth century – especially in France. The uneasy mixture of styles in Grattan’s book is unsettling, and not just because it is aesthetically unpleasing. It is unsettling in the same way as a charged silence. The writing evokes not western New South Wales but itself: craving the authentic, striving for reconnection, eroded by a creeping sense of emptiness, anguished over the inability to fill it.

Comments powered by CComment