- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gender

- Custom Article Title: The Out Coach

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Out Coach

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the era of gay liberation, ‘coming out’ has for many taken on the character of a religious experience. Gays and lesbians in the US draw easily on a religious culture of personal salvation even while denying the sometimes oppressive institutions it has created. In Australia, we are not given to the same public display of emotional and spiritual commitment, but ‘coming out’ has nevertheless come to be regarded as a gay rite of passage.

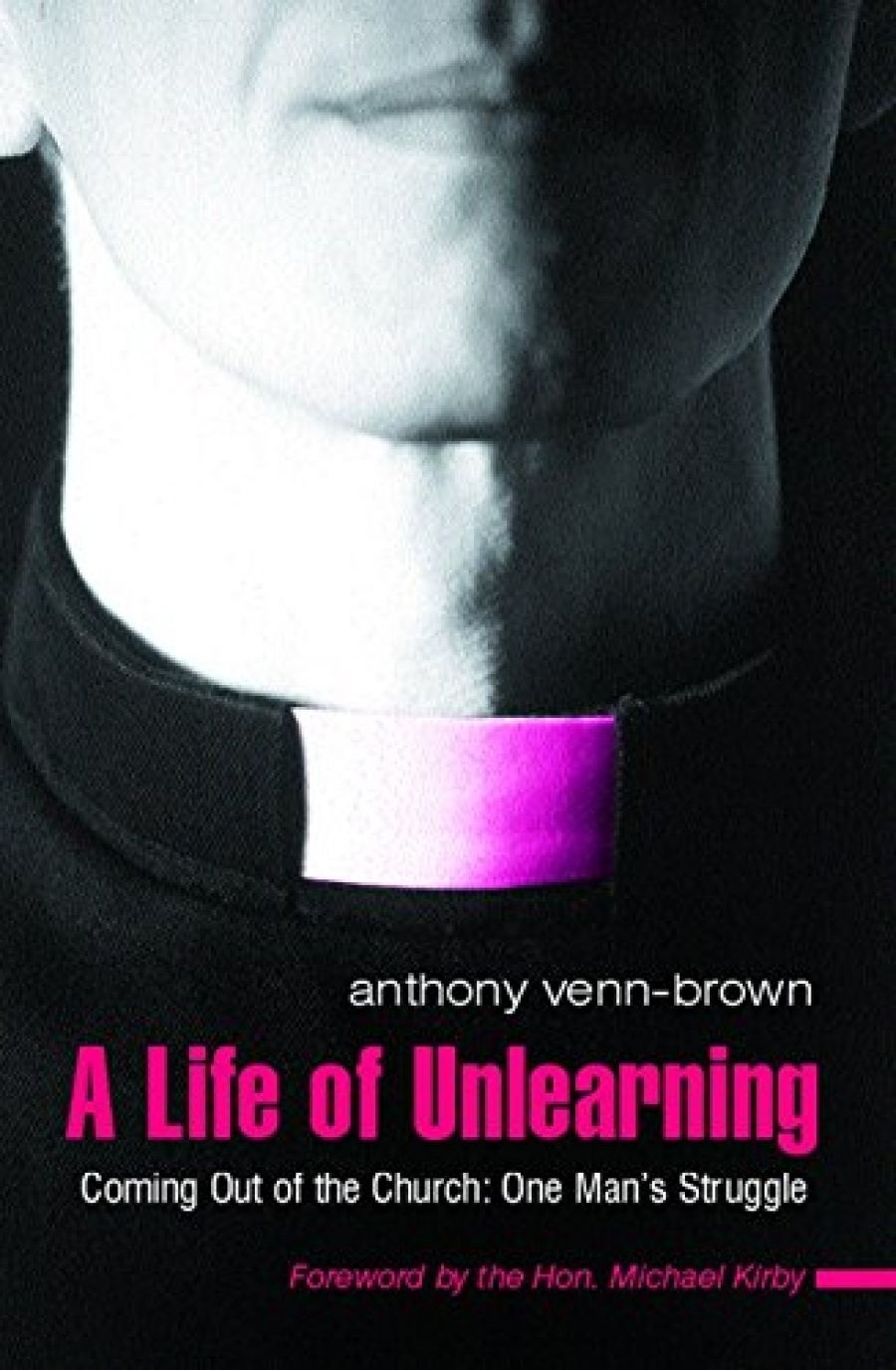

- Book 1 Title: A Life of Unlearning

- Book 1 Subtitle: Coming out of the church: One man's struggle

- Book 1 Biblio: New Holland, $27.95 pb, 319 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The author grows up in middle-class Sydney, child of a family of church-going Anglicans. At sixteen, he drifts away from the church, has a brief infatuation with spiritualism and Satanism before enthusiastically returning to Christianity, being ‘re-baptised’ in the Baptist Church, even while seeking, unsuccessfully, to study for the Anglican ministry. But it is the charismatic movement that finally claims him. When he experiences the crowded, Pentecostal worship of the Christian Faith Centre in leafy Turramurra, he feels he is ‘in the very presence of God’. As he sums it up in the language of marketing, ‘I was sold’. Joining this movement, and finding his vocation as a preacher, brings him marriage, children and reputation, if not worldly success.

Throughout this journey, he is intermittently tormented by homosexual desire, though his outbreaks are often either sexually unsatisfying or a cause for guilt and remorse. The attempts to overcome or eradicate his homosexuality include the conventional referral to a psychiatrist, a morbid and gruelling three weeks of exorcism, and a programme of punitive ‘rehabilitation’ at a gruesome Pentecostal institution, which calls itself ‘Paradise’. When he finally makes the break with church and family, there is a destructive relationship with a lover who turns out to have been HIV positive. Throughout this saga, there are tumultuous personal crises, emotional collapses and tears, lots of tears.

One of the virtues of the book is its exposé of the hypocritical religiosity that so often characterises fundamentalist churches; the happy, hand-clapping singalong, the euphoria of speaking in tongues and the theatrics of public healing are sometimes underpinned by moral authoritarianism and a brutal lack of compassion. The apparent spontaneous informality of much alternative religion and the focus on the charismatic leader allow the few to manipulate and exploit the many.

Finally leaving this world behind him, forgiven by his long-suffering wife and reassured by the love of his two daughters, Venn-Brown throws himself into the gay scene. The language of evangelism gives way to the soft-porn celebration of sexual conquests: Adrian, the gorgeous blond ‘with pecs to die for’; Rod, the actor, ‘in his very tight-fitting Lycra shorts, buns like boulders’; bisexual Bobbie, ‘who kept coming back for more’. He is a regular at the City Gym and in 1995 a member of Locker Room Boys who march in the Mardi Gras, an exhilarating coming out.

A Life of Unlearning would have benefited from more stringent editing. The emotionalism is at times wearing and the self-absorption relentless. The narrative has its banal moments, as when we are told that ‘there is no pain like that of a broken heart when a lover leaves your life’. But if this account of an unusual and traumatic coming out helps those experiencing similar difficulties, it is to be welcomed.

There remains, for me, a question mark over the final outcome of this spiritual journey. When one blissfully happy relationship collapses in curious circumstances after less than a year, Venn-Brown resumes the search for ‘a higher purpose and meaning’ and attends a seminar in Chitzen Itza, Mexico, put on by some unnamed organisation. When one speaker declares that ‘whatever is sacred to a person is sacred’, something clicks and Venn-Brown is set free from the last pieces of his ‘previously judgmental and condemning belief system’. Well, not all of us would be happy with such a bland form of relativism, and it is difficult to reconcile this spiritual free-for-all with his critique of fundamentalism. By page 307 he has convinced himself that he is ‘a good person’, ‘a person of power’ and ‘completely comfortable’ with his sexuality. Religion has given away to an amorphous spirituality.

I find it odd that Venn-Brown shows so little interest in mainstream churches sympathetic to lesbians and gays. What does he make of the Episcopal Church in the US, where the advent of a gay bishop was handled with such sensitivity and openness? Closer to home, the Uniting Church has led the way in recognising its lesbian and gay ministers, while the Anglican Church struggles to do likewise. But then, for all its personal angst and emotional intensity, this is a remarkably unreflective book. Having jettisoned religion, he finds his community in the diversity of gay and lesbian culture – ‘GOD, I LOVE MY TRIBE!’ he concludes.

The story doesn’t quite end there. On the last page you are referred to his website, and there you are offered ‘self discovery, self empowerment and self transformation’. For Anthony Venn-Brown, ‘a passionate student of personal development’, is now ‘a certified coach’. Well, there you go!

Comments powered by CComment