- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Sister Sleuths

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sister Sleuths

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

About to present a lecture to medical students, pathologist Dr Anya Crichton notes optimistically, in Kathryn Fox’s new novel, that the word ‘forensic’ in the title will pretty much guarantee her a full house. Sadly, when the overstressed and overambitious students discover that the topic is not going to figure on their exam paper, a significant number depart, therefore missing out on such compelling topics as how to spot the suspicious death of a diabetic, or when to accuse the family pet of snacking on the deceased.

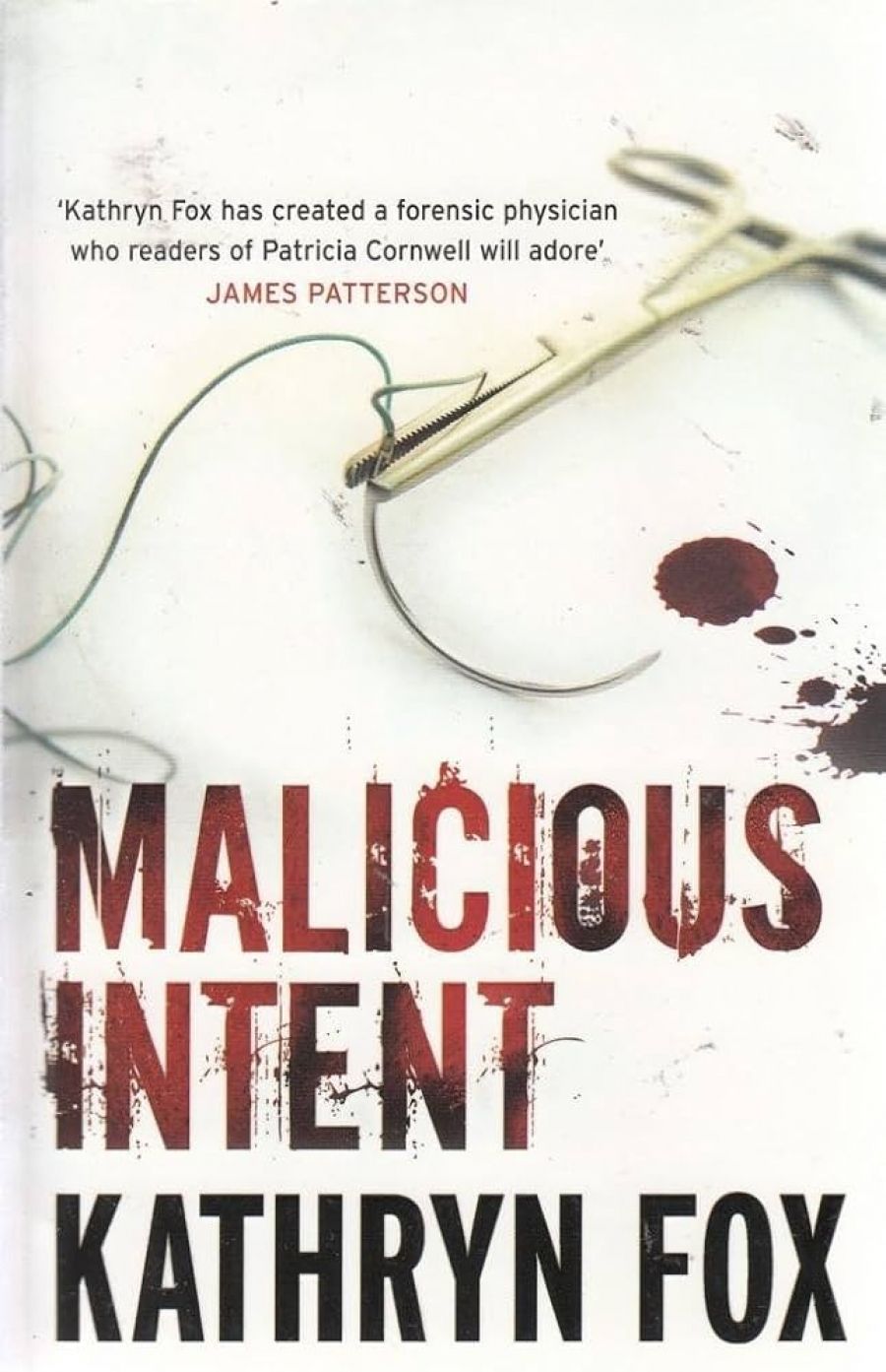

- Book 1 Title: Malicious Intent

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $30 pb, 345 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: The Walker

- Book 2 Biblio: Hodder, $29.95 pb, 362 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

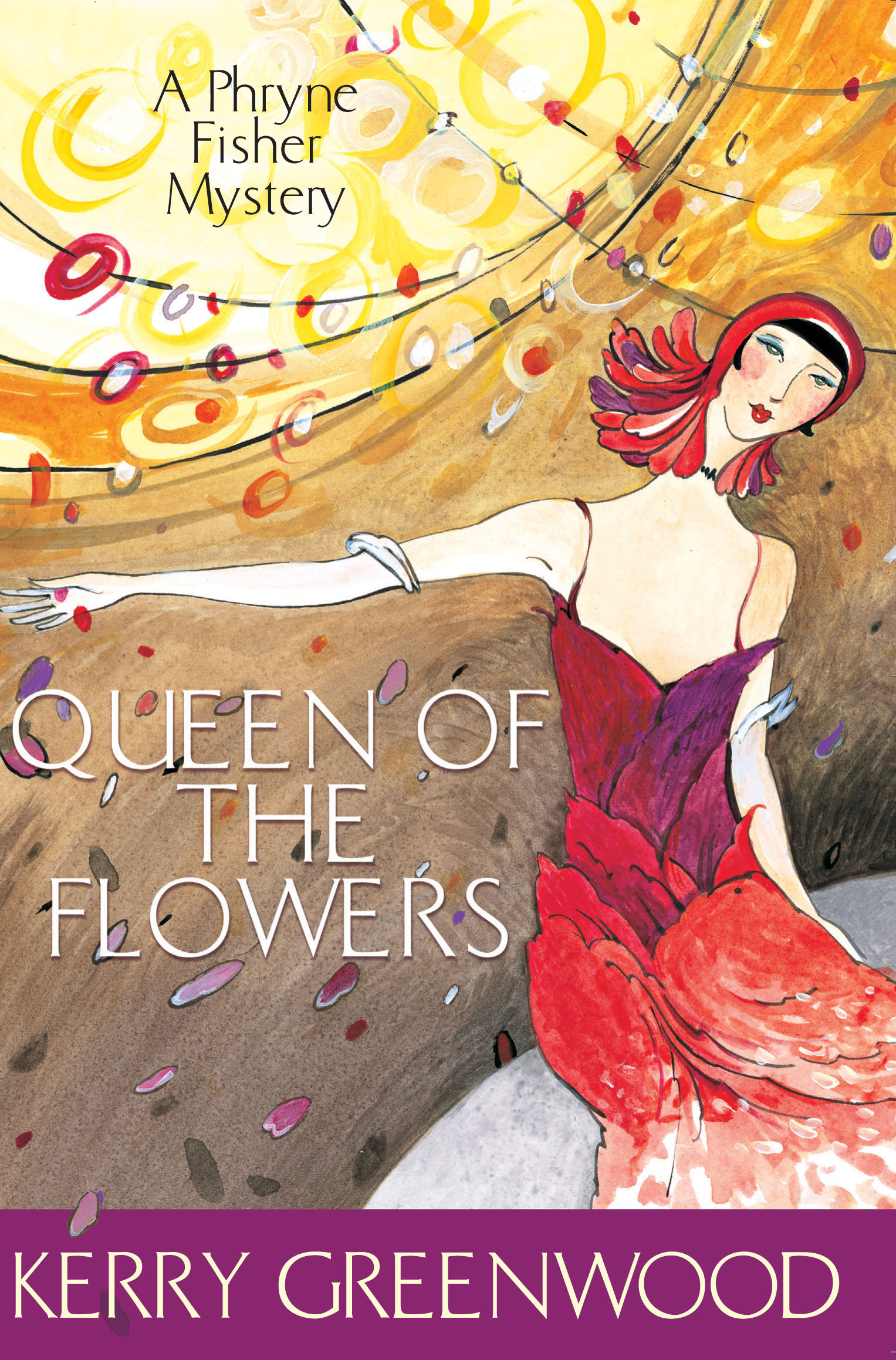

- Book 3 Title: Queen of the Flowers

- Book 3 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $19.95 pb, 279 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Malicious Intent is, however, much better than anything Cornwell has written lately, and much superior to anything Reichs has ever written. Fox may be a medical practitioner, but she knows how to write decent prose, create sympathetic characters and pace a thriller, and she keeps the reader turning the pages. One of the true pleasures of crime fiction is precisely this effect; being carried along by a narrative that barely lets up and, like a good holiday, removes you from the mundane.

But this is hardly an escapist fantasy, since the world of Malicious Intent is compellingly real and closely observed. A single mother who has lost custody of her child, Crichton has to deal with tragedy on a daily basis. Called in by the brother of a dead Muslim girl to investigate her apparent suicide by heroin overdose, Crichton not only has to negotiate the cultural implications of shame and ritual murder, but also threats to her own safety and her already precarious family life. It is a familiar scenario, but Fox does it well, embedding Crichton in a web of relationships and issues that render her achingly vulnerable.

One of the most revealing moments of all, however, is completely tangential to the main plot as Crichton conducts the obligatory medical examination of a middle-aged rape victim. Her solicitude for the traumatised woman and her handling of the procedures involved is an object lesson in how to marry detailed knowledge of medical practice with the revelation of character in action. In the end, it’s all about science, as Crichton’s identification of mysterious fibres in the case of one woman’s death eventually connects the dots with several others and a pattern begins to emerge. It’s all very unsettling and deeply satisfying. A new talent to watch.

Another new talent on the Australian crime scene is academic Jane Goodall who, in company with fellow academic and prize-winning crime writer Barry Maitland, chooses to set her first crime novel in England. Unlike Maitland, however, Goodall’s scenario takes place in the not-so-recent past. It is September 1967, and high school student Nell Adams finds herself alone on a train from Penzance with a bloody corpse. Four years later, she returns to London from Australia to begin her university studies after an interlude marred by panic attacks and a conviction that the killer will eventually come after her. Which, of course, happens.

Goodall shifts from Nell’s perspective to that of Detective Briony Williams, the youngest female detective inspector in the Met, who deals with all manner of sexist assumptions about her role on the force. Williams is part of a team called in to investigate the murder of a professor of anatomy and physiology, whose mutilated and disembowelled body is discovered in his own lab, artfully arranged in the manner of a Hogarth etching. At first the two crimes appear unconnected, but the astute reader knows there is probably a good reason why they have been juxtaposed. Goodall does a fine job of quietly building the reader’s awareness of the links between the two crimes, while leaving the main protagonists in the dark. It is another page-turning exercise as we will the female characters to connect in order to pool their knowledge and to solve the puzzle.

Along the way, Goodall evokes the early 1970s in London well. She does so through fashion (miniskirts and Mary Quant), films (Dr Zhivago and Georgy Girl), music (Joni Mitchell) and various allusions to the chief occupations of the time, switching on and dropping out. Perhaps even more tellingly, she manages to capture the thinly veiled sexism of the time as yet another form of mundane, but no less threatening, menace. Goodall gets it just right.

Less successful are the passages devoted to the point of view of the killer, whose spiritual connection to Jack the Ripper is somewhat of a cliché within the genre. Do we really need another Ripper reference to evoke a serial killer’s psychopathic peculiarity? As a particular bogeyman of 1990s crime fiction, the serial killer seems, well, a tad passé. Nevertheless, Goodall gives us a finely written and extremely competent first crime novel. Another promising début.

Kerry Greenwood, on the other hand, is an accomplished master for whom the latest Phryne Fisher represents the fifteenth in a series that, at worst, has always entertained and, at best, has been astonishingly good. Following the superb Castlemaine Murders (2003), which was a career high, Queen of the Flowers marks a much quieter outing for Phryne, who is back on her home turf of St Kilda, struggling to cope with all manner of local and domestic trials, largely involving missing girls.

Plot A, set in the present of 1928, concerns one of Phryne’s precocious flower maidens in the forthcoming St Kilda Parade, whose behaviour and subsequent disappearance are traced back to a dismal middle-class home where the appearance of gentility masks all manner of nasties in the woodshed. Comeuppance is inevitable. Plot B is set in the past and, as usual, involves some intriguing real-life historical figures and allusions. The skilful interweaving of fact and fiction, actual people and the invented are a standard feature of Greenwood’s literary detective work, usually accompanied by a list of sources and references for the more literal-minded reader.

This latter story centres on one of Phryne’s adopted daughters, Ruth, who was conceived as a result of a romantic entanglement between her birth mother and a Scottish piper. Greenwood deftly unravels this tragic tale in a series of brief letters appended to each chapter. Read on their own, these notes constitute a fine epistolary novella that could probably stand alone. However, Greenwood’s strategy is, as ever, to pull the two disparate plot lines together in a triumphant denouement. It is all, as Phyrne herself might note, very pleasing.

Most pleasing of all is the evocation of Phryne’s everyday reality: the Butlers in the kitchen ever ready to whip up some sumptuous spread or restorative cocktail; Dot, the loyal maid, tut-tutting over the torn stockings and ripped hems of her derring-do mistress; Cec and Bert, the former wharfies with a colourful turn of phrase, always on call to do the dirty work. One senses that if Greenwood’s crime novels ever did make it to the screen, these bit players would steal the show. A bravura performance.

Comments powered by CComment