- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: Degrees of Exploitation

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Degrees of Exploitation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Accounts of past child abuse and the inability or unwillingness of those in positions of authority to confront its reality are amongst the hottest of topics in today’s media. Generally, the story is about the perpetrators and their punishments, or about the impact of disclosures on church leaders forced to retire because of their negligent or political mishandling of cases brought to their attention. But what about the victims? Rules of privacy generally mean that we never learn at firsthand what it must be like to live with the knowledge of a childhood tainted by sexual abuse on the part of some adult with authority. Still less are we likely to know what that knowledge must be like when the abuser was also a much-loved family relation, such as, or especially, a father. For that reason, memoirs such as these are valuable in that they initiate the reader into the long-lasting effects of abuse with graphic emotional immediacy.

- Book 1 Title: A Tuesday Thing

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $22.95 pb, 509 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

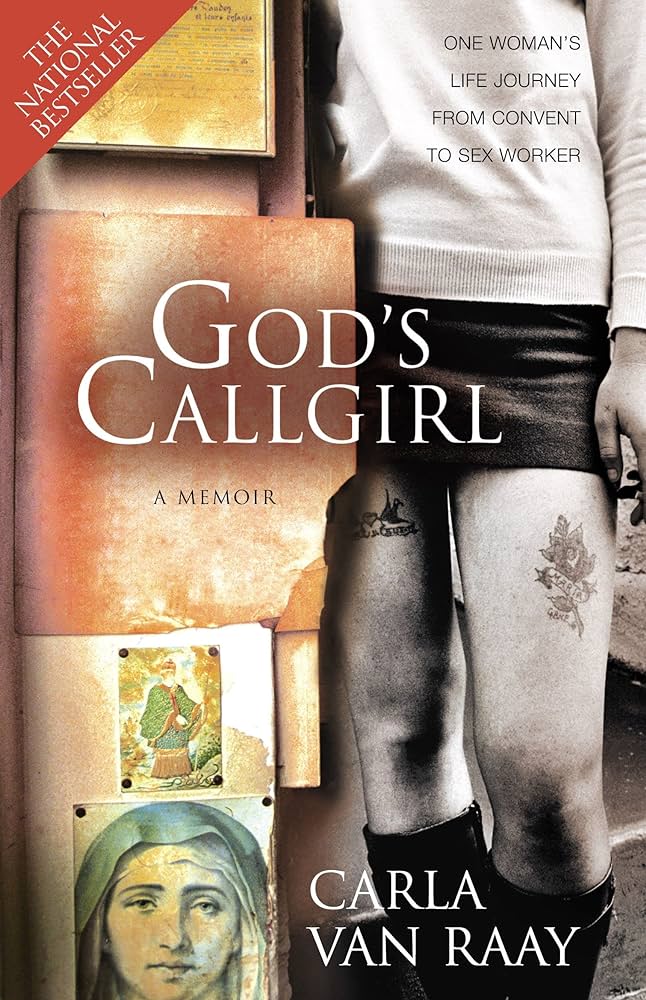

- Book 2 Title: God's Callgirl

- Book 2 Biblio: HarperCollins, $29.95 pb, 441 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Kate Shayler has written a previous account of her experiences as a ward of the state in a children’s home: The Long Way Home (2001). A Tuesday Thing continues Shayler’s story after she left the home. Following her mother’s death when Shayler was four, her father placed his three children into Burnside Homes. Separated physically and later emotionally from her siblings, Shayler is perpetually aware of her lack of family. Thrust into the outside world with almost as little knowledge of it as van Raay, who leaves a convent at the age of thirty, she is afflicted with a conviction of difference and general separation from others. The death of her adored father deepens this acute loneliness, although recalling him is also to risk recalling memories that are too shameful to be shared.

Fortunately, her innate intelligence and capacity for hard work, combined with the sensitivity of some of her co-workers and a few friends, sees her gaining confidence in her work for an insurance firm. Shayler writes throughout in the present tense, which lends daily immediacy and dramatic intensity to her story, as well as providing a sense of progress. The threats to her fragile sense of self-worth, recorded in an anxious inner dialogue, become gradually less strident as her efforts to educate herself are more and more successful. With the help of a small inheritance from her father and of the Whitlam initiative of TEAS, she studies for the Higher School Certificate and eventually takes a Masters degree. Apart from a difficult period with work-shy colleagues, her experiences as a pre-school teacher are overwhelmingly positive and described with obvious pleasure in her abilities with small children. Professional success is not enough to ease the loss of family, however, and the vicissitudes of her search for a loving and loved partner act as a constant poignant undertone to her story.

The last half of her book deals with another betrayal by a figure in authority. During the period of work difficulties, she consults a psychologist with dubious professional standards, who subsequently exploits her love for him and then rejects her. Her pursuit of justice through the appropriate professional standards committee takes four years and encounters many hurdles, but results in the psychologist’s deregistration for three years. In an ironic twist, her habit of keeping a journal as a form of self-conversation helps, on the one hand, to convict her betrayer but, on the other, is another keenly felt invasion. More markedly than van Raay’s memoir, Shayler’s is shadowy as far as other people and places are concerned. Her focus is so entirely on the inner life, and the negative or positive impact on that life by other individuals, that the latter have not much more to them than their names.

Carla van Raay’s memoir, God’s Callgirl, may gain a wider readership than Shayler’s since it describes from the inside the life of a Catholic nun, (before the liberalising effects of Vatican II) and the life of a sex worker. Van Raay was born in Holland into a strict Catholic family, the eldest child of what was eventually a very large family. The chapters describing her early childhood during the German occupation are among the most vivid in her story, especially compelling in their representation of her parents. This father is hugely present: violent, dynamic, fascinating, unpredictable. Divided by class, and by the mother’s powers of caustic wit, the parents are united in their blind obedience to their religion’s strictures. The father is often described as a Jekyll and Hyde figure, delighting the child with his handmade toys and games, terrorising and shaming her by engaging her in oral sex from the age of three. Afraid of exposure, he later beats her into agreeing to silence, a formative experience which she perceives as making her complicit in his guilt.

In 1950, the family emigrates to Australia but remains as isolated as they were in Holland. More distanced from the narrating self than Shayler and more analytical of her confused states of mind, van Raay maintains that her decision to enter a strict Melbourne convent at the age of eighteen was a result of her inability to face life as an adult. Her descriptions of conventual life hold few surprises, except perhaps to uncover religious practices remarkable for their ignorance about women’s health. For van Raay, life as a nun continued the attitudes of loyalty and silence she had adopted from childhood. The reforms imposed on her strict order in 1967 had the effect of releasing her ties of loyalty; she left two years later at the age of thirty.

The subsequent stages of her turbulent life proceed at breakneck pace: a brief marriage and motherhood, followed by more temporary relationships, another child, and then a career in prostitution. First working for pimps, she branches out on her own with some success, at least as long as she convinces herself that she is providing her clients with relief from the stresses of their lives. Little is left to the reader’s imagination as far as physical descriptions of ‘relief massages’ are concerned, although her clients remain virtually indistinguishable from each other. The same applies, surprisingly, to more lasting relationships, including those with her partners and daughters.

As with Shayler, the focus is exclusively on inner vicissitudes. Van Raay’s eventual progress to the point where she is able to discard both her burden of guilt and her conviction that she is a victim is dealt with somewhat cursorily, although a penultimate poem to her father effectively conveys her final serene state of mind.

Comments powered by CComment