- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: True believers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

These two new collections are both by, and maybe for, believers. They contain passionate and interrogative poems that argue for and celebrate their respective views of the world. Both poets are, to quote Rosemary Sorensen’s term for Goodfellow on the cover blurb, ‘evangelists’ who wear their respective hearts on their sleeves and who urge or invite assent.

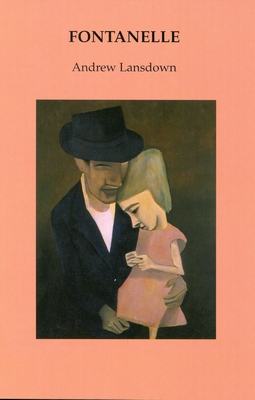

Fontanelle, Andrew Lansdown’s seventh collection, is concerned with the almost ineffable immanent design and intricacy of the natural and experienced world, especially of birds, insects and a young family. The role of the poet here is to explore, describe and celebrate the (almost) sacred in the mundane: ‘The words I’ve been working with / are like running water. All afternoon / I’ve been trying to scoop out / a place for them to settle …’ (‘Home’). Lansdown’s voice is earnest, reverent, wonderstruck. These are Romantic imagist poems in which the poetry defers to the empirical and ontological world: ‘Cicadas have left their cuticles / clinging to the daisy stems: / brown shells, burst at the back / of the thorax’ (‘Emergence’).

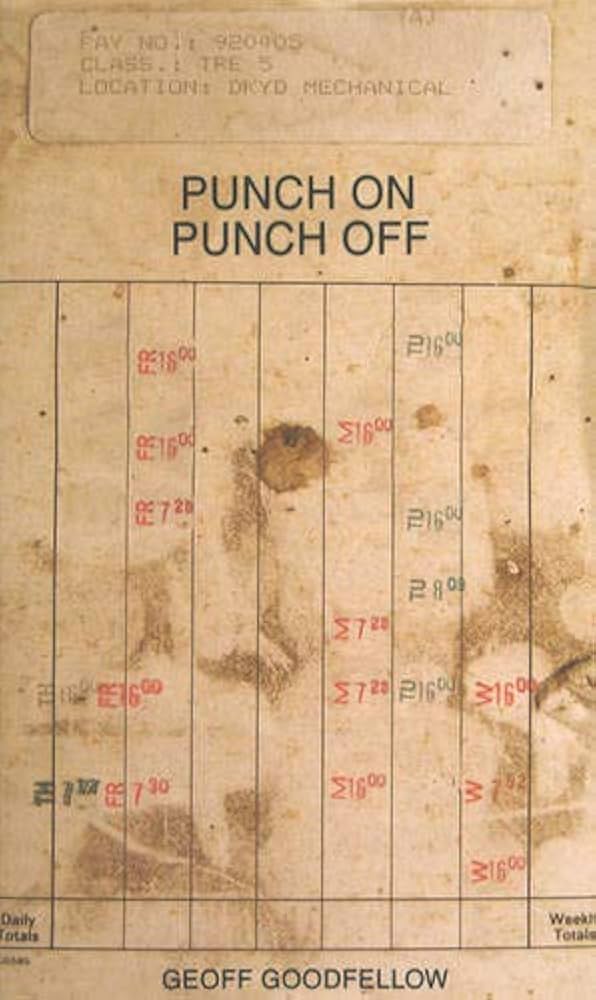

- Book 1 Title: Punch On Punch Off

- Book 1 Biblio: Vulgar Press, $14.95pb, 71pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Fontanelle

- Book 2 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $18.95pb, 112pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Punch On Punch Off, however, Goodfellow’s eighth collection, is concerned with the all-too-effable world of political realities: the workplace: ‘i mean it’s hard enough holding back / a pee for three or four hours … / let alone your tongue at times …’ (‘The Luxury of Work’); the home: ‘The Lonely / Sit at home taking calls / from hotel chains / re-roofers / paint companies …’; and social inequalities: ‘but would Mister Thompson know / the weight of workers’ / steel-capped boots / or just the weight of coin / required to replace a pair’ (‘Poetry in the Workplace’). The poet is a commentator, an agitator, reminding readers of their and his origins, the importance of working-class values and family wisdom in the face of capitalist success and dominance. Goodfellow’s voice is edgy, ironic, polemical: ‘i still had my fingers last / Monday to Friday / punch on punch off’ (‘The Violence of Work’). Both collections focus on the outside world from an ideological point of view; the poetry is a vehicle for persuasion, illuminating understanding and depending partly on the voice of the poet. Both argue for compassionate hearkening to la condition humaine and to the plight of the vulnerable. However, both books are strikingly different from each other – obverses, in fact.

Lansdown’s poems are written in a subtle, lyrical, almost pristine language, whereas Goodfellow’s are slangy, vernacular and brash. Lansdown’s stance is polite, pastoral and almost ecstatic, whereas Goodfellow is confronting, iconoclastic and demotic. Lansdown’s poems are static and rural, Goodfellow’s restless and urban. Lansdown writes about art, literature, home, while Goodfellow writes about work, power, relationships. In Lansdown’s poems, the external world is almost eternal and fixed; in Goodfellow’s, the world is pressed in on by time and circumstances. In Fontanelle, humans may be self-actualising and in control of their fates and understandings, but in Punch On Punch Off humans are victimised. One collection is ‘metaphysical’, the other ‘political’; one is meditative, the other polemical.

Lansdown is a deft miniaturist, concerned with the precise splendour of small things and the way the microcosm displays the macrocosm. His most preferred form of poetry in this volume is the haiku. Elsewhere, the stanzas are finely sculptured and the poems rather brief. Lansdown sees himself as the inheritor of Matsuo Basho’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North (see ‘Journey’).

At their best, Lansdown’s poems reveal jewelled, epiphanic moments (see the writing about dragons in ‘Shock’, or the almost Pre-Raphaelite clarity of ‘Apples’, with its almost casual ‘Some things about women / a woman can never know’) – in context, mind. But at other times, the poems cloy and seem childlike, oversimplified, and self-consciously pietistic. For me, the easy invocation of Christian metaphysics creates a didactic barrier (as in ‘Learning to Believe’ or ‘Christmas Tree’), despite their clever craftsmanship.

Goodfellow is something of a provocateur and haranguer. He wants to argue about the quintessential Australian (and human) virtues and defining qualities: ‘Bluey … likes pubs where real blokes / make a real earn[ing] moving TVs / videos CDs lawn mowers … or whatever else can be pushed / or carried / or lifted.’ Often in these poems one feels oneself being asked to consider and acknowledge that what is really important is that being human involves refusing to accept existing social strictures.

Goodfellow’s concern with time and order is not so much metaphysical or ontological as political, so that, for example, ‘time’ is something that enforces political and social consequences and often makes personal life difficult because of the economic consequences of time-measurement: ‘& as we raise our knives & forks / we try not to get indigestion / as we both try to sneak glances / at the kitchen clock / knowing that time may never be / on our side’ (‘The Grind’). At times, Goodfellow’s tone becomes insistent, as in ‘Swanston Street’, or perfunctory, as in ‘Write that he said’ and the ending of ‘Family Secrets’.

Nevertheless, these are both accomplished books with strong, distinct flavours. Although there is a proselytising element to the poetry in both collections, there are intelligent, multi-layered pleasures from the considerable craft of both poets for even the most sceptical of unbelievers.

Comments powered by CComment