- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bleak vision

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Here is a kind of social experiment in fiction. Take the lowest, most abject starting point for a human life. Give the child no advantages, home or family; provide it with no regular food or care; subject it to the privations of a society with no welfare system; deprive it of any educational, emotional or spiritual training; and then, when it finally finds an occupation, make it the lowest, most socially disadvantaged and despised. And then see what kind of person it turns out to be. Oh, and set the whole thing in the Middle Ages, which, as everyone knows, was the most brutal, depraved, disease- and poverty-ridden era in Western history.

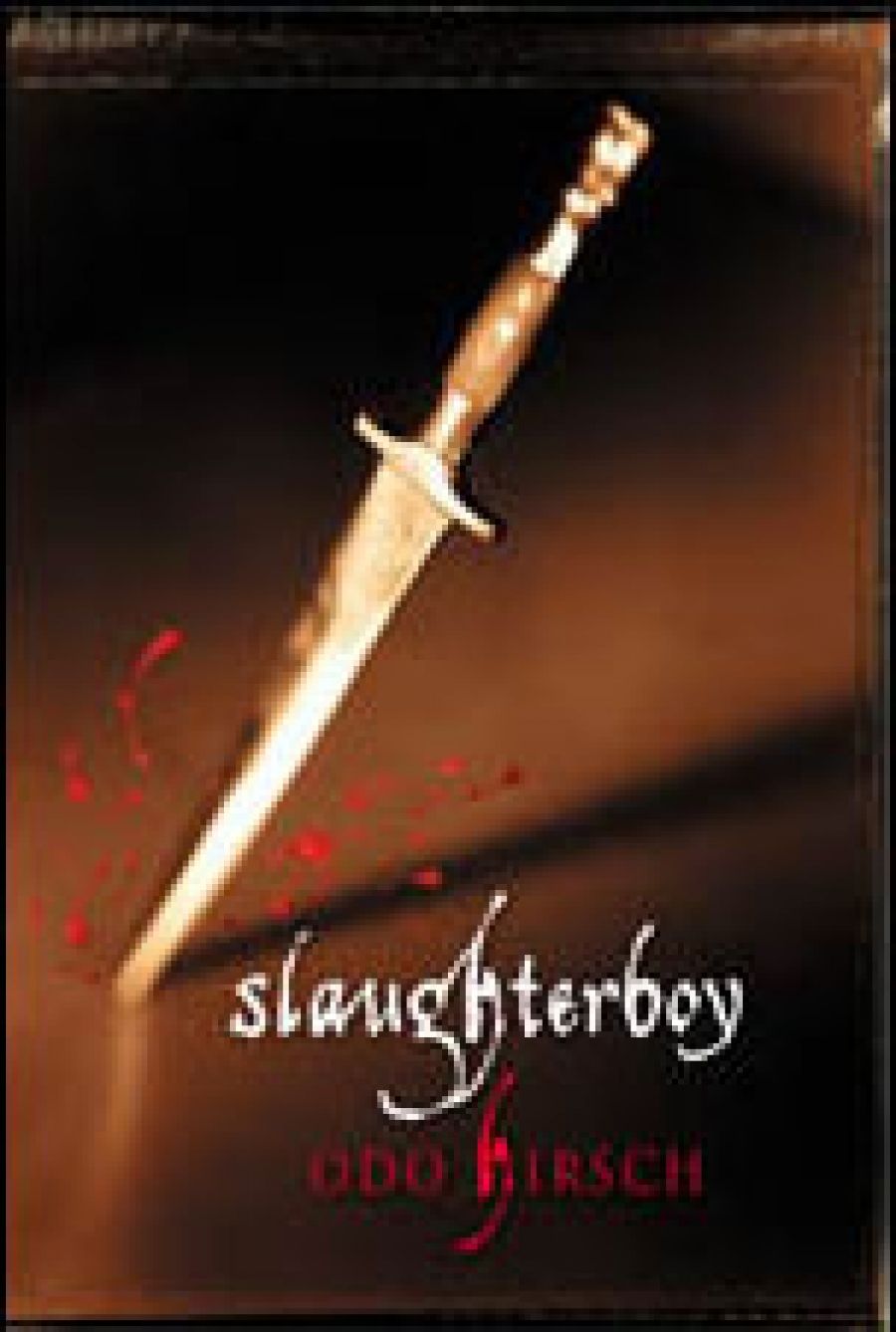

- Book 1 Title: Slaughterboy

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $16.95 pb, 317 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

These are the premises of Odo Hirsch’s new novel, Slaughterboy, whose central character, Conrad, is discovered by a bailiff and a gravedigger at five years of age, mistaken for a pile of rags at the feet of a dead woman. The novel traces the next fifteen or so years of his life, as he moves through a succession of stages in bare subsistence. Unable to sell the foundling to anyone, the bailiff is about to take him to an orphanage, but Conrad escapes and finds a group of children who live by scavenging on the streets. They are held together by need and a kind of community, but their group in turn is fractured by death and emotional betrayal, and Conrad exiles himself from their company.

In the first of a series of ‘career-moves’, he attaches himself to a ‘slaughterman’, one of the town’s butchers, despised for the bloodiness of his occupation. ‘The adults themselves regarded the slaughteryard with a sort of superstitious dread, as if the things that happened there embodied some kind of malevolent power. It was a place of blood, death and dismemberment.’

The writing here is typical of Hirsch’s style in this novel. The weak gesturing of ‘some kind of’ after ‘a sort of’ leads us only to an unspecified ‘malevolent power’, but this is quickly reduced to the simple, literal naming of the things found there: ‘blood, death and dismemberment.’

Hirsch deliberately reduces his narrative focus in this novel, seeking to capture the restricted emotional range of Conrad, the various self-serving professionals he deals with, or the simple view of ‘the adults’, ‘the people’ or ‘the crowd’, especially in the riot scenes during the famine that threatens the town. When the narrative finally ventures beyond the town walls into an idyllic country scene, it comes as quite a shock, so powerfully has Hirsch represented the desperate, often claustrophobic atmosphere of the town. Slaughterboy is at its most dramatic when presenting this dehumanised vision:

The town was like a great heaving stomach that churns and mixes and digests all manner of food with the sharp acid of its juices. It produced nothing, yet consumed all. Its appetite was insatiable. Send it more, always more. Send corn, fruit, cheese, fish, fowl and meat. Above all, meat. Pigs, cattle, goats and sheep.

The novel presents almost no redeeming or empathetic characters: unlike traditional fiction for children, the central character does not embody any special virtues of sensibility or courage and does not turn out to have any kind of mysterious destiny or concealed identity. There is no invitation, then, for readers to identify with Conrad. If anything, we are invited to see him as the Hunger Boy, the devilish changeling of European folk tradition who first eats all the food in the house, and then starts to consume the children. The one emotional point of focus in the novel is Conrad’s affection and respect for the slaughterman and his wife and child. This moment of domestic happiness is brief, however, and Conrad soon becomes an assistant to the ‘doctor’.

The setting of the novel is medieval, but only vaguely so. At times, Hirsch appeals firmly to a Monty Pythonesque stereotype of medieval abjection, disease and filth. At other times, his town seems more like a humanist city, especially in the scene set in ‘Ink Yard’, ‘where the educated people of the town came not only to look for books, but to talk’. The doctor, similarly, deploys the worst cynical excesses and superstitions of medieval medicine, while displaying a seventeenth-century interest in human dissection. Most of the characters’ names are Germanic-sounding, while Bread Lane and Threadneedle Street imply a London location. For a late medieval setting, too, the town is entirely secular.

The absence of even a corrupt church (another familiar trope of medievalist fiction) suggests that Hirsch’s principal concern is to explore the moral, emotional and psychological effects of a life of deprivation and hunger: a medieval environment where the church has no presence is the most economical way of presenting a life without social services.

Slaughterboy presents a bleak vision, indeed. Readers will be challenged to consider whether Conrad’s life of broken attachments is a function only of poverty in medieval Europe, or whether Hirsch’s social experiment can be read as a stronger allegorical representation of modern urban life.

Comments powered by CComment