- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Doors to Emotion

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The eighteenth-century French Academician Buffon gave the world the aphorism ‘Le style est l’homme même’. It makes a fine epitaph for H.G. Kippax. Harry Kippax was a distinguished journalist and, for more than thirty years, until his retirement in 1989, a theatre critic of singular authority and style. In the late 1950s, while employed by the Sydney Morning Herald, he began to write thoughtful freelance reviews under the pseudonym Brek in the fortnightly periodical Nation; in 1966 the SMH’s editor J.D. Pringle press-ganged him into the theatre critic’s chair.

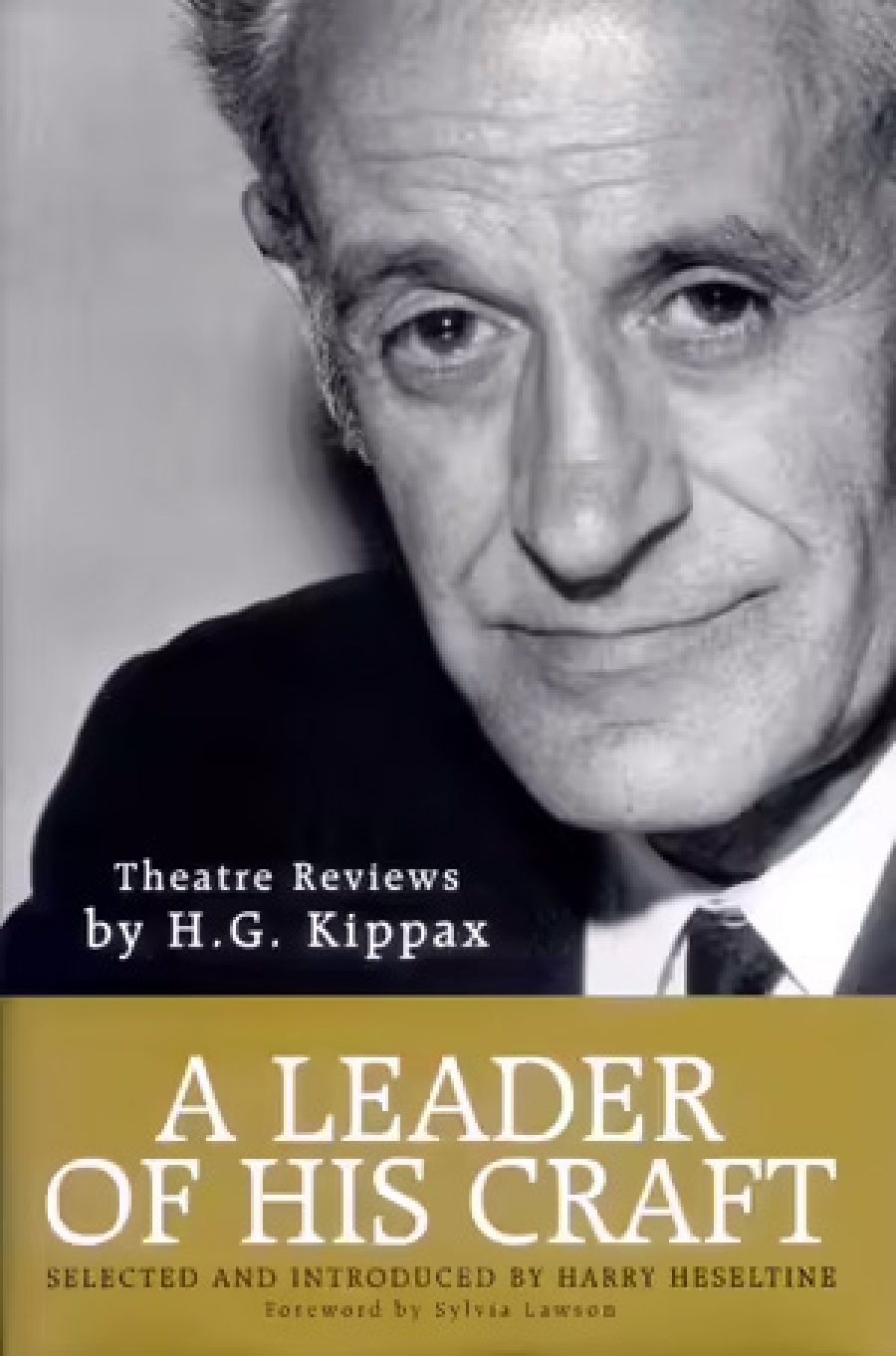

- Book 1 Title: A Leader of His Craft

- Book 1 Subtitle: Theatre reviews by H.G. Kippax

- Book 1 Biblio: Currency House, $45 hb, 336 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Theatre professionals believe that those who are paid to judge them should first have dirtied their own hands. Kippax served his time with the Sydney University Dramatic Society during his war-interrupted undergraduate years, when he studied part-time under the terms of his cadetship with the SMH. His war service included his last practical experience of making theatre: Corporal Kippax produced several plays for the troops.

Two postings to London and one to New York were the Fairfax organisation’s serendipitous finishing school for its future SMH critic. In both cities, Kippax saw several plays a week, forming standards by which he later judged productions, actors, and new writing. Not long after he was recalled to Sydney, Kippax would have noticed that Harold Hobson, alone among London critics, welcomed a challenging new writer, Harold Pinter. Two years later, Kippax performed a similar service for Patrick White with his review of The Ham Funeral.

Kippax wrote about 2,500 words in Nation for that notice, more than three times the length of this review. He concluded: ‘It is a long time since I have had such an exciting evening in an Australian theatre.’ Note the placement of that frankly subjective statement; the facts and judgements that precede it are stated more objectively. For instance, ‘drama’s richest resource is language, not for its own sake ... but as the key which unlocks the greatest numbers of doors to reveal emotions and ideas’. Earlier, Kippax had found in White’s expressionist play ‘a way out of the impasse in which Australian drama finds itself’.

The forty-odd years since that review appeared have shown that expressionism did not solve the style dichotomy epitomised by Douglas Stewart’s verse drama on the one hand and the backyard realism pioneered by Summer of the Seventeenth Doll on the other. It took nearly a dozen more years before David Williamson showed the way – and H.G. Kippax was there to welcome him. Reviewing The Removalists, he wrote: ‘I repeat what I said about Don’s Party – that its author, Mr David Williamson, is, on the strength of these two plays, in the top flight of young dramatists in the world today.’ Kippax recognised good writing for the stage and wrote persuasively about it.

This volume includes almost eighty reviews of plays published in the SMH, plus a small selection of Kippax’s annual reports on Sydney theatre. The review of John Bell’s Lear of 1984, supported by ‘Judy Davis’s brilliant double ... a strong, luminous Cordelia, and the Fool, a fey, cockney-comic boy’, has typically attracted from Currency House’s splendid editors the heading ‘A Lear Worthy of the Masterpiece’. Of Jane Street Theatre’s 1979 production of Waiting for Godot, Kippax wrote: ‘Of the good cast I particularly admired Mr Mel Gibson’s Estragon.’ His eloquently stated reasons followed, and then the perceived strengths of ‘Mr Geoffrey Rush ... a fine mime and a sensitive actor, missing, for me, only the intimations of heroism in Vladimir as intellectual and optimist’.

Unlike many critics of earlier generations, Kippax did not believe that his primary task was to acclaim and describe great acting. He examined, and honoured if appropriate, writing, acting, directing and sometimes design. With his old-world courtesy titles of Mr or Miss for every theatre worker, he characteristically conveyed a sense of what it was like to be in the theatre on the night of the performance under review.

Reading the SMH reviews and the twenty-five longer pieces from Nation brings Kippax back: in his case, the style was indeed the man. Speaking of style, Sylvia Lawson’s foreword is warm, personal, and relatively informal, contrasting with Harry Heseltine’s more scholarly introductory essay and the invaluable contextualisation provided by Currency House’s editors in the form of footnotes and some synoptic introductions. In such a setting, Kippax’s gentle but firm prose is lapidary, semi-precious, more valuable for not being flashy. One hopes that his younger Melbourne contemporary Leonard Radic of The Age may be assessed for a similar volume. The one eminent theatre critic with a national brief during the Kippax–Radic era was Katharine Brisbane, whose period at The Australian (1967–74) may not have been quite long enough to generate such a useful work of practical reference as this.

Comments powered by CComment