- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Love Letter

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Victoria’s coastal borough of Queenscliff is fortunate indeed to have esteemed poet and scholar Barry Hill (a local resident since 1975) as its official historian. He combines an eye for events that will resonate as part of the ‘big picture’ of Australian history with a local’s affection and instinct for the telling details that pinpoint the intrinsic character of the place.

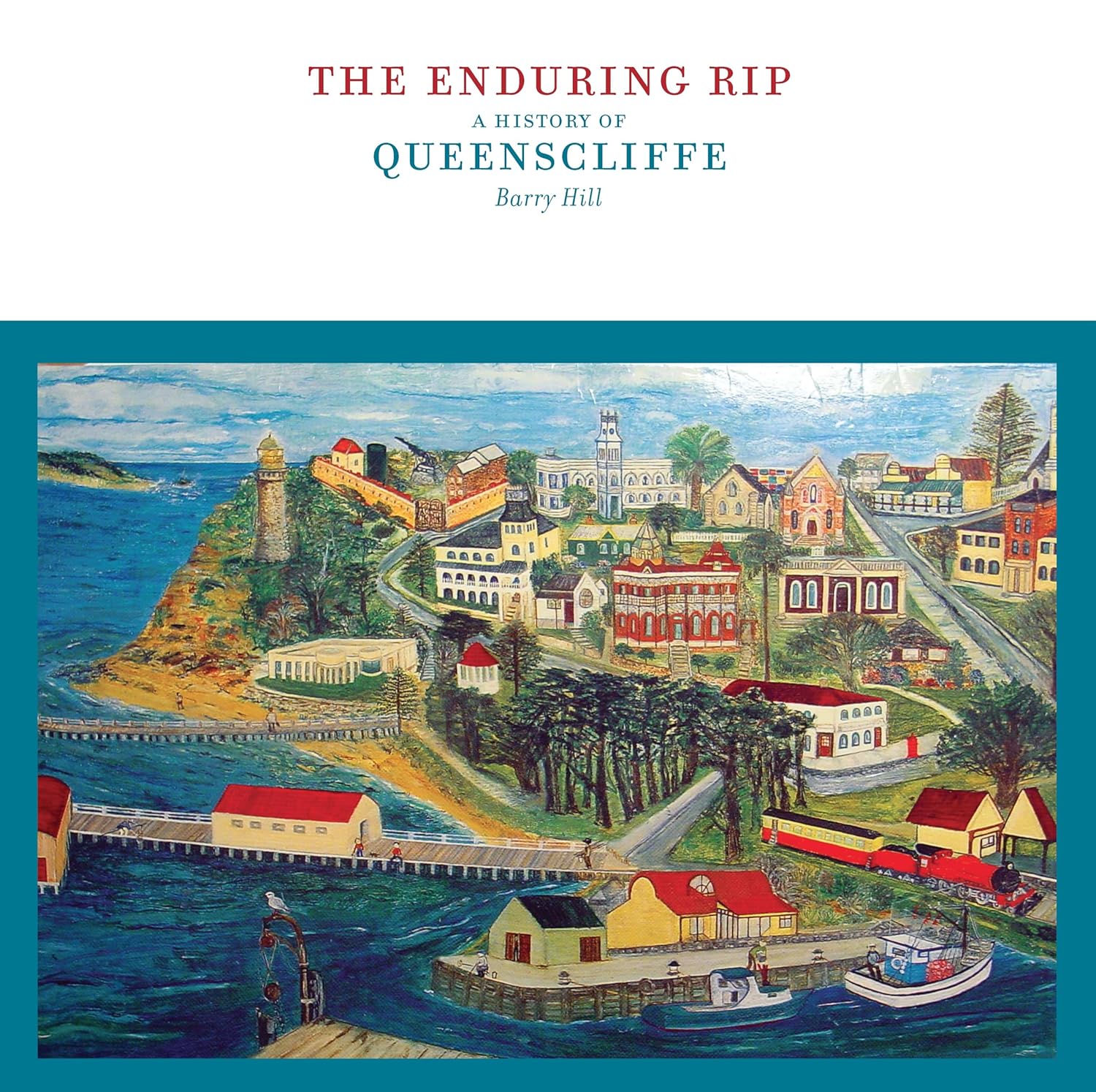

This book was partially written in the Queenscliff Historical Museum: at a mess table recovered from a shipwreck, surrounded by vintage diving equipment, a skull recovered from the sea, music boxes and silver teapots. It is an apt metaphor for the character of the town: on one hand, a sedate seaside resort known in its heyday for its boarding houses, grand hotels and ‘solid respectability’; on the other, a notorious shipwreck site and home to both a military barracks and, more recently, an Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) training ground for spies.

- Book 1 Title: The Enduring Rip

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of Queenscliffe

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $49.95 pb, 312 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The earliest boat on record to negotiate the Heads and disembark at Queenscliff was The Lady Nelson in 1802. First contact with the original inhabitants was optimistically characterised by ‘dancing on both sides’, followed by a friendly exchange of goods. Sadly, this serendipitous state of affairs did not continue beyond a day, and relations between the would-be colonisers and the Aboriginal inhabitants subsequently followed a more typical pattern of conflict and distrust. This pattern is punctuated, however, by Australia’s most extraordinary tale of European–Indigenous relations: the saga of ‘wild man’ William Buckley, the convict who escaped from Victoria’s first settlement in Sullivan’s Bay, on Christmas Day, 1803. Soon adopted by the local Wathaurung people, Buckley lived happily among them for more than thirty years, eventually making his way back to white society and acting as an intermediary between the settlers and natives.

Hill’s background as an indigenous historian is evident throughout these early sections of the book, where his knowledge of the subject shines effortlessly through. There is no feeling of tokenism in his inclusion of the indigenous experience as part of this history: instead, there is a sense that it is an inseparable part of the narrative. His language when he writes of Indigenous–settler conflict is also telling: he makes open reference to the ‘frontier killings’ that characterised the town’s colonisation, not bothering with euphemisms.

The story of Queenscliff’s early colonisation and gradual development as a fishing village and seaside retreat is lovingly told, with as much care taken with the experience of the fishermen, pilots, teachers and councillors who formed the backbone of the town as with personalities of national significance, such as Alfred Deakin, who had his holiday home there.

The main threads in this history are the town’s connections with fishing and shipping (not to mention shipwrecks), the military and the traditions of its hotels, guesthouses, swimming baths and ferries – the tools of the trade for a sea-side tourist destination. The rise and fall of the fortunes of these very different industries help tell the story of not just the town but of Queenscliff as a microcosm of the nation.

Australia’s involvement in both world wars is viewed in the context of events at Fort Queenscliff (its military base) and the strong pro-conscription stance of the townsfolk during the national referenda under Prime Minister Billy Hughes. The little-known fact that in February 1942 a Japanese seaplane took off in Bass Strait and flew north over Fort Queenscliff (not to mention the Darwin bombings) highlights just how close that war came to our shores. Late in the book, our post-September 11 involvement in ‘the war on terror’ is mentioned in relation to the tight security surrounding the ASIS training camp on Swan Island, which specialises in covert operations (or ‘Dirty Tricks’). Hill chillingly points out that this makes Queenscliff a prime military target.

The twin declines of the local fishing and tourist industries are traced with a discernible sense of regret for a way of life that has disappeared. A series of interviews with the last of the fishermen is particularly well done, evoking the smells and sounds of days gone by, and perfectly capturing the fierce passion that his interviewees hold for their home.

This love letter to Queenscliff is informative, engaging and suffused with warmth and character. The book is enhanced by a selection of exquisitely chosen photographs and illustrations, including some magnificent seascapes. My only quibbles are minor editorial ones: the Americanised spelling throughout an Australian local history couldn’t help but annoy the pedant in me, and Queenscliff is spelled inconsistently throughout: it has an ‘e’ on the front cover, no ‘e’ throughout the back cover blurb, and alternates between the two spellings inside the covers. Quibbles aside, this is a local history that any town would be proud to have, and one that can be thoroughly enjoyed by many who live beyond the borders of Queenscliff.

Comments powered by CComment