- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Whether you agreed with it or not – and many didn’t – Samuel Huntington’s prediction of a coming Clash of Civilisations (1993) was one of the most engrossing arguments of the late twentieth century. He not only foresaw Western civilisation confronting a joint Confucian–Islamic challenge, in 1996 he also anticipated an attack on the US by young, middle-class Muslims.

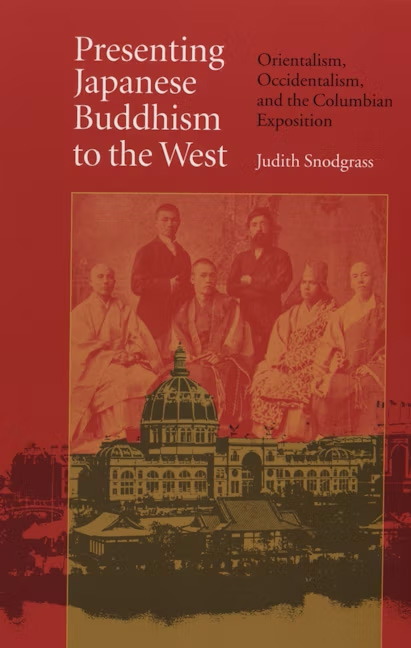

- Book 1 Title: Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West

- Book 1 Subtitle: Orientalism, Occidentalism and the Columbian Exposition

- Book 1 Biblio: University of North Carolina Press, US$21.50pb, 351pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Judith Snodgrass, writing a year before Buruma and Margalit, explores much earlier manifestations of such ideas in India and particularly in Japan. She shows how, in the late nineteenth century, religious leaders in both countries deliberately used civilisational arguments to contest the West’s claims to superiority. An authority on Buddhism, Snodgrass didn’t detect ‘bad ideas’ either in Swami Vivekananda’s claim that Indian spirituality was of a higher order than anything in the West, or in Anagarika Dharmapala’s audacious argument that Christianity was in fact derived from Buddhism.

Snodgrass shows how the Meiji-era Japanese saw the 1893 Parliament of Religions in Chicago as an opportunity to prove themselves the equal of the West in front of an international audience. In particular, they shared the Japanese government’s desire to be rid of the unequal treaties that had been imposed by the US and that gave Westerners in Japan impunity from ‘barbarous’ Japanese law. So the Japanese delegates waged a contest of civilisations, comparing the behaviour of Western imperialist Christians with ‘real’ Christianity, and warning that, as long as this gap between principle and practice continued, the Japanese could not take Christianity seriously. Even Japanese Christians, who no more wanted American Protestantism in Japan than their Buddhist compatriots did, used their faith to secure proper respect for Japan in the West. Snodgrass summarises: ‘The future world religion would be Japanese. The [only] contest for them was which of the Japanese religions.’

The Parliament of Religions, organised and chaired by a Chicago civic leader, John Henry Barrows, was less democratic than its name suggests. Snodgrass describes the event as aggressively American, Christian, Protestant and supremacist. In spite of rhetoric about international goodwill, it was, she says, ‘an arena for the contest between Christians and the “heathen”, with all that implied about late nineteenth-century presuppositions of evolution, civilization, and the natural right of the West to dominance over the East’. So Barrows was bound to clash with Hirai Kinzo who, in fluent English, accused Western powers of claiming Japanese were uncivilised heathens in order to avoid revising the treaties. Buddhism as practised in Japan was not only more scientific, moral, and enlightened than Christianity, the Japanese delegates argued, but it was also superior to the religious practice of any other Asian country. The Parliament was held during the Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which commemorated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to the New World and displayed America’s modern achievements. White racial superiority was a central idea behind the Exposition. Evolution, according to Social Darwinists, had brought the US to its divinely ordained place in world history, and this was symbolised in the design of the Exposition: from the Dome of Columbus with North America on top, and White City (the vast US display), to the elegant but traditional surroundings of Old Europe, descending through Asian folkways to African villages. Determined, in the face of this hierarchical schema, not to be dismissed as merely Asian, the Japanese negotiated to have their pavilion occupy a separate island, opposite the American neo-Grecian colossus.

The pavilion was constructed on the site by Japanese craftsmen and was a recreation of the Phoenix Hall of the Bodoin temple near Kyoto. The original was built in the eleventh century, a period when Japan was isolated from China and Korea. Through it, Japan could claim sole credit for the splendour of its ancient civilisation and the modern advancement of its technology. Displaying the opulent lifestyle of a cultivated Japanese gentleman, the pavilion implied a contrast, as well, with the benighted Middle Ages in eleventh-century Europe. The Phoenix Hall was greeted with fascination and amazement by visitors to the Exposition, and afterwards the Japanese government donated it to Chicago, where it remained for many years. But for all Japan’s efforts, it didn’t secure revision of the treaties. That took three wars.

Snodgrass’s story is fascinating on several levels: as a detailed analysis of the Exposition and the Parliament of Religions; as a dissection of the veins and arteries of Japanese thought at the time; and as a point of reference for what’s happening inside religions today. It’s often said that September 11 changed the world, but this book suggests that the more it changes, the more the world remains the same. So in the twenty-first century, Japan is still dedicated to holding Expos, to donating its artisan-constructed pavilions to host cities, and to demanding to be recognised as the equal of the West and superior to the rest of Asia. The US continues to claim world hegemony, manifest destiny, extraterritoriality, and advancement beyond ‘old Europe’, and to assert its right to decide between good and evil and to wage crusades against those who disagree. Civilisational superiority is still asserted by Chinese and Indians over the West, and religious superiority by many Muslims: for Islamists, Western slights to their holy places justify holy war. As in the nineteenth century, hypocrisy persists in countries that, while they claim to be democracies at home, support dictators abroad; that talk about free trade but practise protection; and that say they want international peace and disarmament but sell arms and invade other countries when and where it suits them. The only real difference is that now we have the United Nations, whose member states denigrate it for standing between their ambitions and their betrayal of its principles. This story is essential reading for anyone who participates at a deeper level in the continuing discussion about the Clash.

Comments powered by CComment