- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Triumph of the Stonefish

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 9 October 2004, 13,098,461 electors were enrolled to vote for the federal parliament. The Australian Electoral Commission’s website records 11,715,132 electors having voted for the House of Representatives on a two-party preferred result. So much for voting in a federal election having been compulsory since 1911. And not a few will have left the polling booth wondering, ‘Why bother?’

- Book 1 Title: A Win and A Prayer

- Book 1 Subtitle: Scenes from the 2004 Australian election

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $16.95pb, 132pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

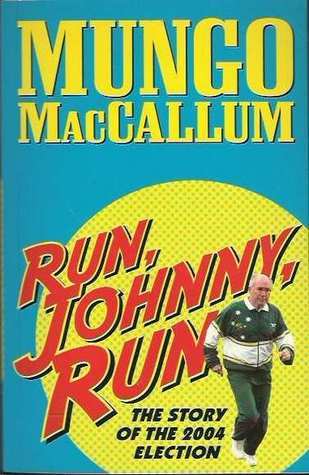

- Book 2 Title: Run Johnny, Run

- Book 2 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $22pb, 286pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

it captures the essence of the man, both in his lack of personal appeal; and his success as a politician. The stonefish is a sluggish and rather stupid predator with neither flair nor dash; it waits for its prey to come to it and then kills by treachery. And, time after time, it gets away with it. The secret, of course, is in its appearance: as the name implies it resembles a rock resting in the sand of the seabed, totally harmless and ordinary, even boring. But behind the innocuous disguise is one of the most poisonous and lethal creatures on earth. The trouble is that by the time the victim realises the trouble he’s in, it’s too late; he is already at best stupidified and at worst beyond help.

For MacCallum, the prime minister,

posing always as a modest conservative, has dealt destruction to the Australian tradition on an extraordinary scale, transforming the country in less than a decade from an open and generous nation, tolerant and optimistic in its role as a respected member of the world community, into a selfish and timid appendage of a crusading superpower caught up in the superstition of Armageddon and apparently quite happy to cooperate in bringing it about. In the process the public service has been drained of its independence, the judiciary seriously undermined, the national parliament reduced to a farce and the office of the prime minister, once regarded as no more than the first among equals, turned into an unaccountable commissariat ruling by absolute fiat.

In much of this devastation Howard has been aided by a cowed and incompetent political opposition and some smug and acquiescent media. But this does not excuse or explain the way the Australian public, notoriously disrespectful of politicians as a class and sceptical about both their warnings and their promises, has continually returned him to power. The alternative may not have been madly attractive, but surely it has had more to offer than the dishonesty, the meanness, the divisiveness and the simple nastiness of the Howard régime.

MacCallum’s thesis is simple. The electorate has consistently fallen for the oldest trick of all, the naked appeal of those most basic of emotions: fear and greed. The goal of the entire electoral process, indeed of Australian democracy itself, has ‘become the re-election of John Howard. Nothing else mattered. The Stonefish rules.’

For MacCallum, How- ard does not deserve to be prime minister, yet he has extraordinary political survival skills. Howard is now the longest-serving prime minister after Robert Menzies; he achieved a 1.79 per cent swing to the Liberal–National Coalition in the recent House of Representatives election, when many thought he was past his use-by date. He will be remembered for more than advertising Vodafone when out on his morning walk.

MacCallum is no Theodore White, author of The Making of the President series, but the analogy may not be too fanciful. Nor does he offer self-indulgent reflections in the style of Bob Ellis’s Night Thoughts in Time of War (2004) or of Margot Kingston’s Not Happy, John! (2004). MacCallum is irreverent, at times downright rude, and he seems to have spent a significant proportion of the election period debating the key issues with his mates in the front bar of the Billinudgel Hotel in the north of Byron Shire. But he is also an extraordinarily well-informed, politically astute, witty, passionate man. Love him or hate him (and there are probably very few political groupies standing in the middle of this debate), MacCallum’s Run, Johnny, Run is one of the best books on Australian politics and society to appear in a long time.

A Win and a Prayer: Scenes from the 2004 Australian Election is a totally different publication. No laughter here, no scatological jokes, although the chapter on the farce of ‘The Battle for Wentworth’ cannot but make the reader smile. But can the media please stop referring to the three main candidates – Peter King, Malcolm Turnbull and David Patch – as all being barristers, Turnbull is not a barrister.

These short essays include ‘The Dog That Didn’t Bark’, in which Geoffrey Barker makes the disheartening observation that ‘Australians are easily distracted from security issues during election campaigns by politicians hurling fistfuls of dollars and shouting “Trust us!”’. Equally worrying is Peter Mares’s ‘Unfinished Business’, a sad account of a hard-working group of refugees from Afghanistan harvesting fruit and vegetables in the Victorian Mallee region and of the supportive local federal member, John Forrest, the National Party whip, who has received letters from constituents telling him that he was not representing their interests and calling him ‘a mad loony lefty’, and worse. Further north, in the marginal Queensland seat of Hinkler, where One Nation pulled in almost a fifth of the vote in 1998, Labor distributed an election pamphlet during the campaign that decried the ‘illegal foreign workers’ who were ‘stealing Australian jobs’. As Mares points out, this fear-mongering is misplaced, and Labor has failed to appreciate the changes underway in rural and regional Australia.

The last two essays, Brian Costar and Peter Browne’s ‘How Labor Lost’ and Rodney Tiffen’s ‘The Aftermath: Must Labor Lose?’, will surprise many who believe that the surprising swing to the Coalition in the House of Representatives has made many marginal seats ‘safe’, and that Labor can expect at least two terms in the wilderness. As Costar and Browne argue, the 2004 result ‘does not herald the end of the Labor Party; it does not mean the Coalition will rule forever; and it does not rule out a change of government in 2007’. The Liberal and National parties lost five consecutive elections between 1983 and 1993. As Tiffen notes, Mark Latham is being blamed by some for the loss, but, as Carmen Lawrence has asked, would the train smash have been worse with another leader?

Australia went into the election with a strong economy, low interest rates and a government running scared and throwing money around like a drunken sailor. Those promises (or were they ‘non-core’ promises?) now have to be met – or there will be many disillusioned voters next time round.

Comments powered by CComment