- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A Living Bridge

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

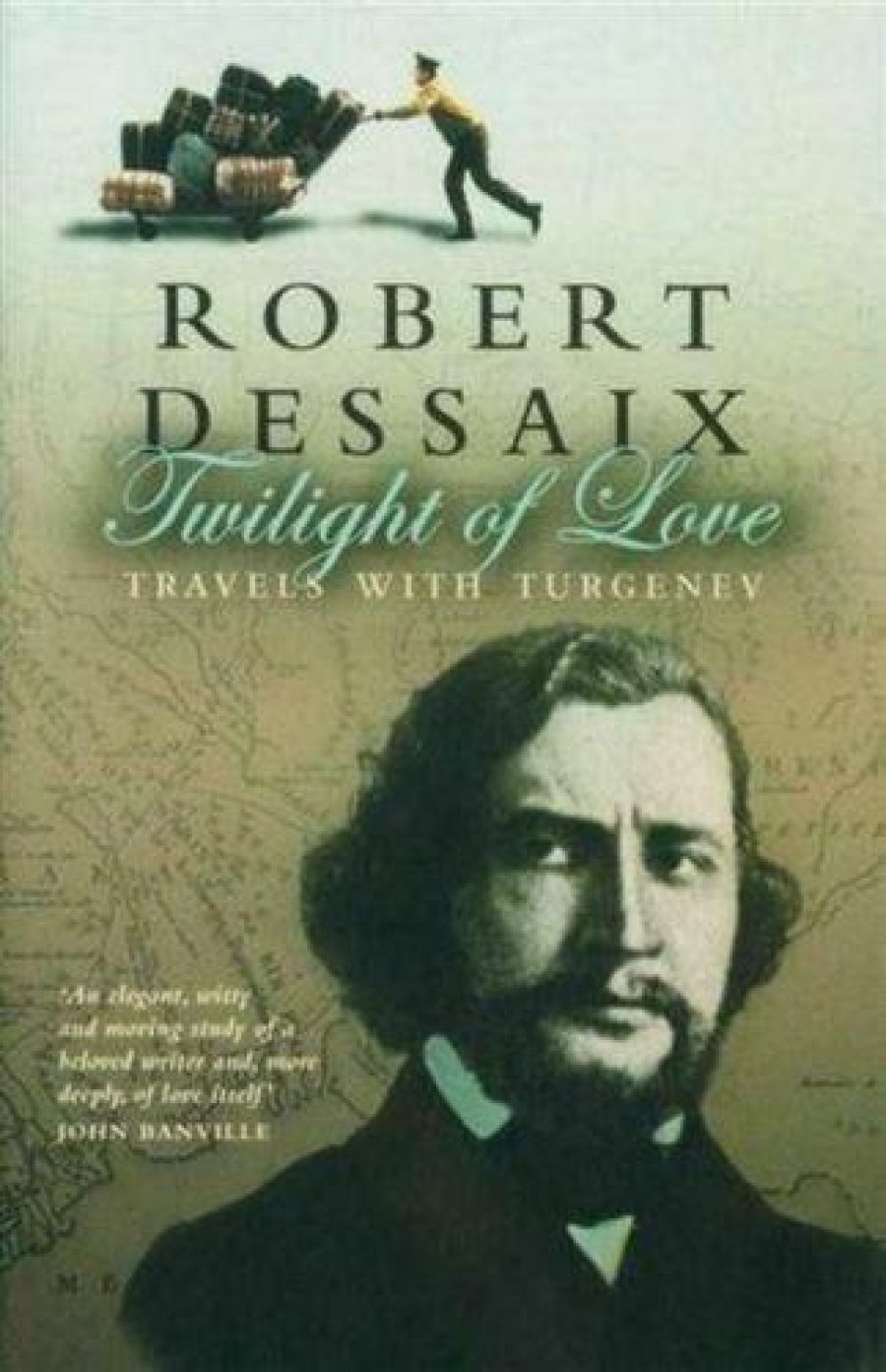

In October 1843 the Russian writer Turgenev heard the opera singer Pauline Viardot perform in The Barber of Seville in St Petersburg; for the rest of his life, he remained in thrall to her in an apparently chaste relationship sustained within the framework of her existing marriage. The story of this devotion, and the view that such a love is impossible in the twenty-first century, are the pivots of Robert Dessaix’s new book, Twilight of Love: Travels with Turgenev. Dessaix never loses sight of his central argument. But he is not a linear thinker, nor a simple writer. He swoops and dives, deft and sharp as a wattlebird, over a range that is spiritual and intellectual as well as geographic and temporal. His book concerns itself with much beside the significance of the relationship between Turgenev and Viardot: a distinctively Australian apprehension of Europe; the experience of travel; the ways in which loving relationships can bring depth to travel and vice versa; the links between history, tourism and imagination; economic and social upheavals in Russia; and the nature of civilisation, to mention only a few.

- Book 1 Title: Twilight of Love

- Book 1 Subtitle: Travels with Turgenev

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $40hb, 275pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

One of Dessaix’s enduring seductions is his capacity to hold opposites in fine balance: thus, he is Australian as well as European, and both funny and profound; his prose is conversational yet elegant, sophisticated yet direct. He contrives also to be plural as well as singular: Dessaix the writer regards Dessaix the tourist with precision and irony, as an essential participant in the book’s unfolding, and locates himself as a tourist in the scenery (both literal and metaphorical) as it unrolls about him. This detachment doesn’t impede a passionate awareness of his surroundings. Yet those surroundings, having been established with attentive specificity (‘outside the boulangerie beneath Turgenev’s windows, breathing in the smell of freshly baked bread’), repeatedly melt into the background, ceding to the past (‘On a fine winter’s afternoon, if you’d been passing, you might have seen him pottering off in the direction of the Tuileries’), which again re-dissolves into a dry response to the present-day Tuileries (‘this mournful, gravelly expanse’).

These images fade and reshape, dreamlike, in the cross-hatching of time and place; but the book contains tough thinking as well as dreams. For one thing, it tackles the tricky nexus between tourism and historic celebrity. Tourists (especially Australians, perhaps) are susceptible to the twin qualities of oldness and proximity to fame: Dessaix is as open as anyone to the special thrill of contiguity, although he is not above satirising it: ‘So he had stood here, he had walked through these very gates, he had … but was this the right house?’ But he readily questions its unreliable charm, particularly when confronted by the deadness of memorabilia (‘under glass a row of fob-watches, pens, assorted photographs together with bills from the tailor and letters of no consequence’).

Twenty-first-century readers may be inclined to cynicism when pondering the absorption Viardot inspired in Turgenev. Naming things is important: today we would call Turgenev’s fascination something different – an extended psychotic episode, perhaps, or a delusional fantasy – and present-day attitudes to ménages à trois are likely to be more pragmatic (and perhaps less salacious) than those of Turgenev’s contemporaries. Whether this represents a gain or a loss is anyone’s guess. Dessaix argues the case for loss, claiming that through our incapacity to appreciate such a relationship for what it is worth in terms of fidelity, lack of self-interest, and even sheer style, we have lost a subtle but genuine dimension of love.

In search of this love, Dessaix uses contemporary Europe as a lens through which to explore nineteenth-century Europe. His journey’s complexity emerges slowly, through a series of almost casual observations that spring from immediate experience (‘One thing I couldn’t help reflecting on as we set off back to Paris …’; ‘Just a few minutes’ walk from my little hotel in Eichstrasse … is the street Turgenev first found rooms in when he moved to Baden-Baden’), which he adeptly links to Turgenev’s own explorations. The trope of exploration provides ballast for the book, but never becomes a dead weight. In his leisurely travels through Turgenev’s life and fiction, Dessaix entwines reality and imagination, and reveals, wry conjuror that he is, how hard it can be to tell them apart; he demonstrates also how sometimes, when one is chasing something else, one finishes by confronting oneself.

Despite false starts and destroyed panoramas, Dessaix’s quest – not only to follow Turgenev but to ‘hear his voice’ – eventually succeeds: ‘I’d recaptured something. I’d felt like a living bridge across the chasm of time.’ The territory through which this lucid and gentle book roams has unexpected keyholes and quirky corners – as well as luminous prospects. By following Dessaix, we too may hear something of the voice of Turgenev, and understand more about ourselves.

Comments powered by CComment