- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Loving and Killing

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘It is in love that violent desires find the greatest satisfaction,’ wrote Stendhal in On Love (1842). Though distanced by land, sea and centuries, Sophie Cunningham’s début novel, Geography, gives contemporary testimony to the same enduring claim. Set for the most part among the suburbs and landmarks of Melbourne and Sydney during the 1990s, Geography travels back and forth in time and place between Los Angeles and Sri Lanka, establishing an expansive mise en scène for this explosive meditation on the complexities of love, sex and self-destruction.

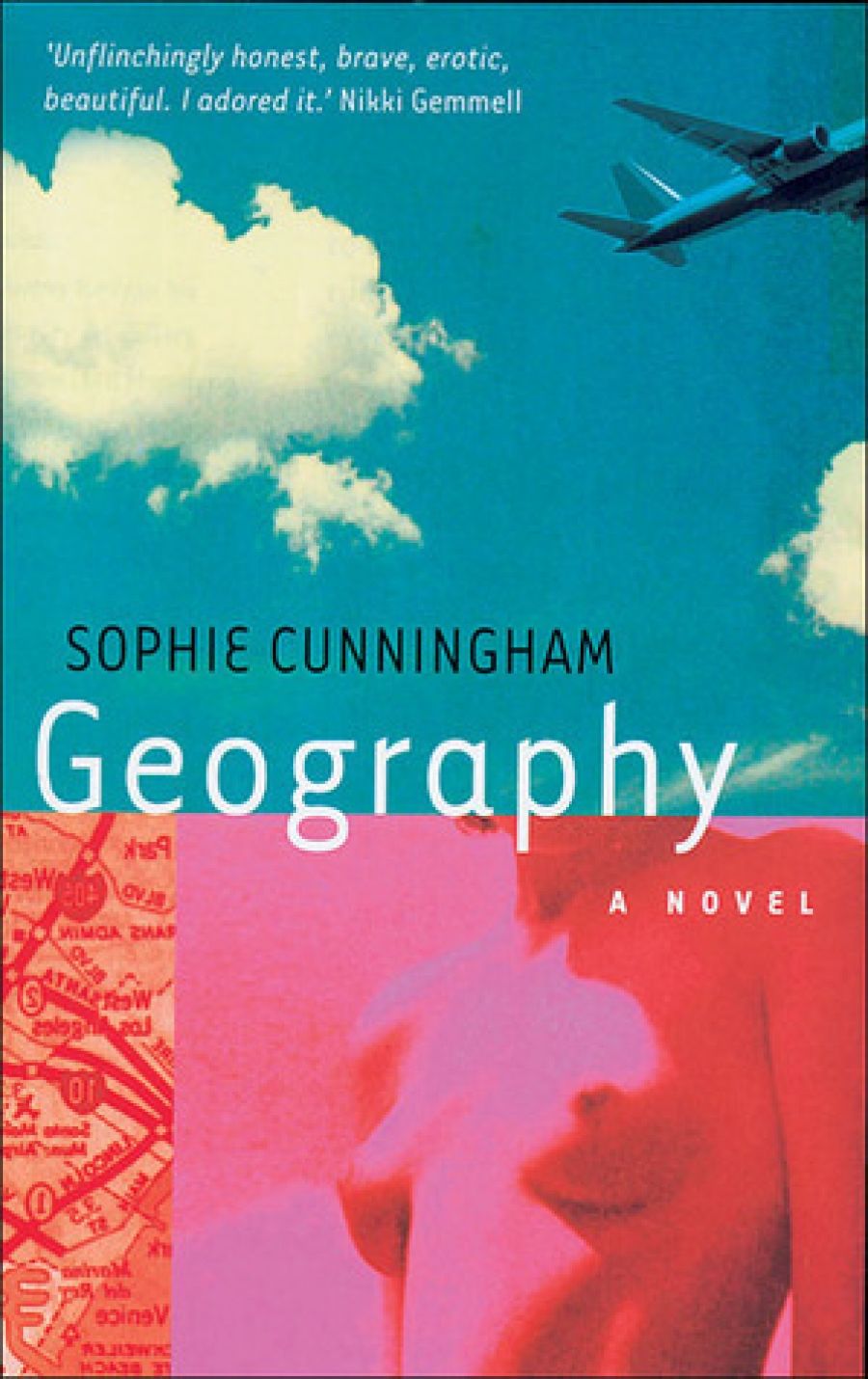

- Book 1 Title: Geography

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $25pb, 208pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

For Catherine, it is a pilgrimage of self-discovery, a reconstruction of the self that was fragmented during the long-term narcotic reverie of a violently addictive love. At the end of the novel, Catherine contemplates ‘how quietly you can lose years. How gently they can slip away from you.’ Yet, from the first chapter, Cunningham propels us head-first with the intense velocity of fresh lust into the narrative of Catherine’s eight-year long-distance affair with the LA-based Michael and builds an intricate cartography of contemporary post-feminist desire.

Cunningham’s text is bold and unapologetically graphic: ‘Fuck me hard, fuck me really hard, turn me around, bend me over, fuck me from behind, bite me,’ urges Catherine during her first encounter with Michael. However, what begins as simple ‘no-ties’ sex gradually envelops Catherine in a hothouse of romantic obsession, which, being largely unre- ciprocated, eventually plunges her into suicidal depression.

Recurring explorations of the motif of ‘geography’ are clever and varied. We learn that Catherine is an avid map collector, that she enjoyed an affair with her high school geography teacher, and that extending the limits of both sexual explorations and physical journeys has been a necessary stopover on the itinerary of personal discovery and present recovery: ‘as I became more consciously sexual, the pleasure lessened. I had to chase harder to find the feelings. What began as an opening to pleasure became a way of closing down. Sex became like the dreams of travel … Both took me out of myself until it seemed there was no getting back.’

In many aspects, Geography is reminiscent of Canadian author Betty Lambert’s banned novel Crossings (1979) and, to a greater extent, of the lesser-known Leslie Dick’s Without Falling (1987), both of which examine the shattering of psy-chic integrity and the loss of self to a violent love, in a pain- fully personal and profoundly feminine territory.

With a text that reads at times as part autobiography, part confessional, and with her use of textual recollection for what appears to be a kind of therapy, Cunningham echoes another aspect of these female authors’ writings of the masochistic love affair. By obtaining authorial control over the experi-ence, the pain of loss and abandonment may be healed; through retelling her story to Ruby, Catherine realises that ‘the main character in this story, she isn’t me. Not anymore.’

Cunningham controversially encapsulates some of the many ambivalent complexities faced by contemporary women as they attempt the risky negotiations of feminism and heterosexuality. Catherine says: ‘I call myself a feminist. But this is my secret, this is many women’s dark secret … the passivity that eats away at me, away at us.’ Her writing courageously depicts the unsanitised contents of an often contradictory female pleasure which feminism sometimes fails to accommodate or refuses to admit. Yet, with its universally relatable themes of lust, love, longing and betrayal, Geography will be appreciated by male and female readers alike.

At the novel’s conclusion, Catherine is reunited with Michael for what is to be one of their final and most shocking encounters: ‘I get out of the car and push him against it, keep kissing him while he puts one hand under my shirt, undoes my jeans with the other … we end up clawing at each other, half-hitting, half-embracing. I want you to kill me, I think. I want to die.’

In her text Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing (1994), Hélène Cixous developed a notion of effective literary power visualised through vivid metaphors of violent pleasure and masochistic transcendence, asserting that ‘loving and killing absolutely cannot be disentangled … it is simply a question of designating the scene or scenes of abandonment that punctuate our paths’. If, as she claims, ‘all great texts are prey to this question: Who is killing me? Whom can I give myself to kill?’, then Cunningham’s brave and refreshing novel can certainly take its place as one of them.

Comments powered by CComment