- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Wylde for to hold, though I seme tame’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Inga Clendinnen came rather late to Michel de Montaigne, the man she acknowledges as ‘the Father of the Essay’. When the professional historian began reading the great amateur, she did so, Clendinnen admits, ‘in that luxurious mood of piety lace-edged with boredom with which we read the lesser classics’. The boredom quickly dissipated as the writer in Clendinnen met a master: ‘It is hard to explain what makes his essays so enchanting, but I think it is the lithe, athletic movement of a naturally intrepid mind.’

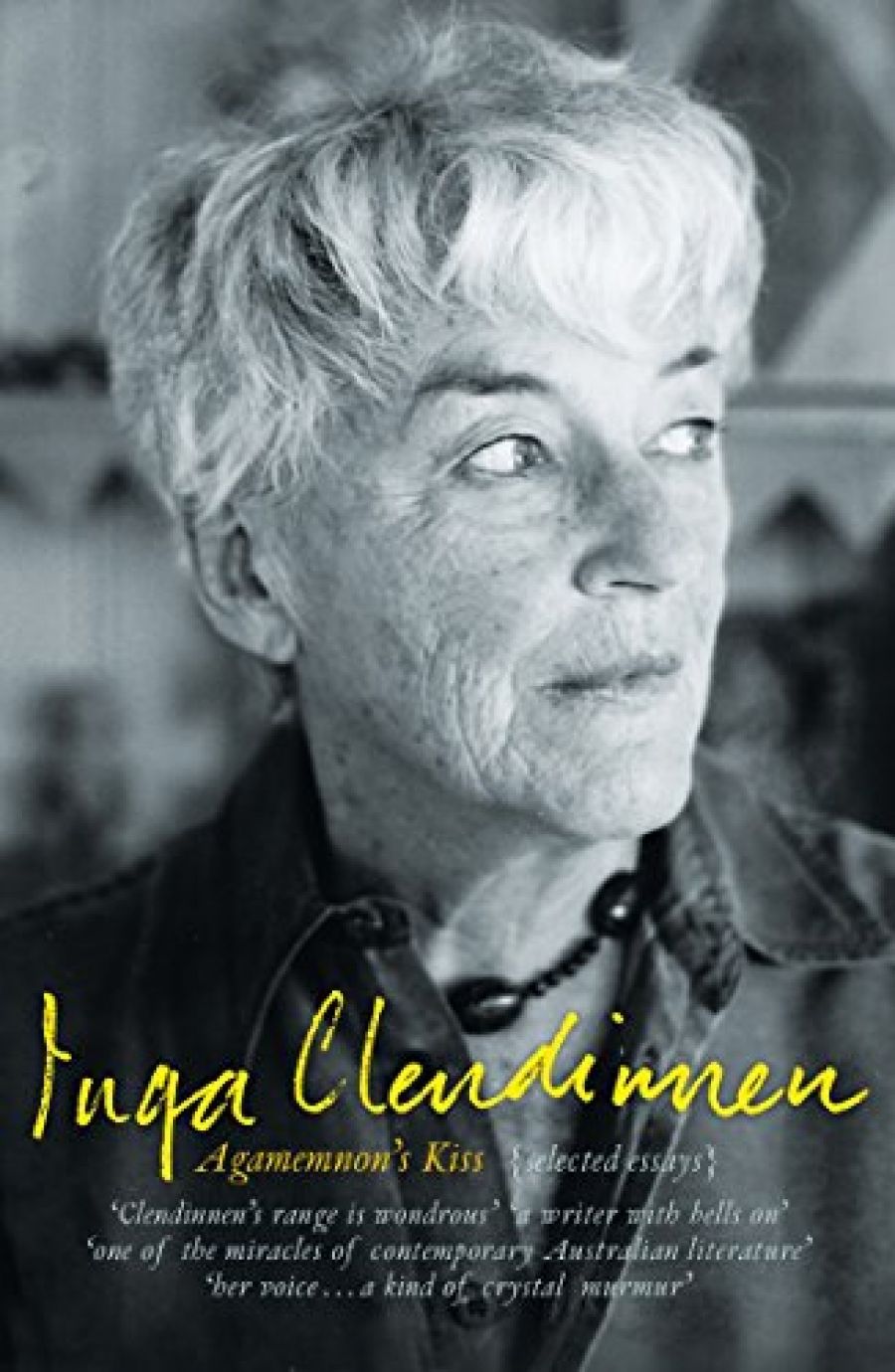

- Book 1 Title: Agamemnon’s Kiss

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected Essays

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $32.95 pb, 230 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

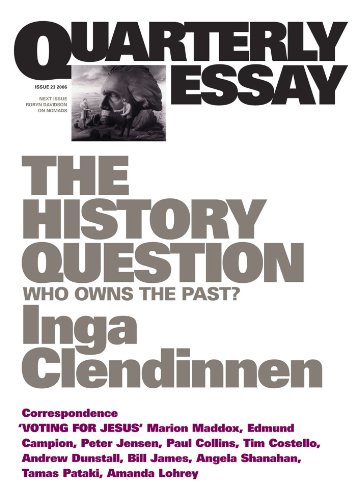

- Book 2 Title: Quarterly Essay 23

- Book 2 Subtitle: The History Question: Who Owns the Past?

- Book 2 Biblio: Black Inc., $14.95 pb, 115 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is not hard for a reader of Clendinnen to explain why Montaigne should chime with her, why the writer Clendinnen should recognise in him a spirit so in tune with her own. ‘Intrepid’ is a favourite adjective of hers, a marker of intellectual valour. And for a fearless, impatient writer (‘I have never been of docile temperament’), Montaigne’s protean curiosity must have been a gift: ‘Unpredictable in everything except his intelligence’, she says of him. ‘He talks about anything because he is afraid of nothing.’

Clendinnen would not herself presume to stand on a dais alongside Montaigne, and no sensible reader would put her there. Like the restless, graceful, enquiring Frenchman, she is too smart ever to be grandiose. Like him, she is ‘seeking the truth, not laying it down’, and a certain modesty, as well as irony, is indispensable to such an ambition. But when Clendinnen remarks of Montaigne that ‘His moral force comes from that mobile, fearless intelligence’, then a comparison, at least, is apt. One reads Clendinnen for exactly that: for the serious delight of tracking a fierce intelligence on a path – or paths – to discovery, discovery that has moral resonance.

There is something else there too in the happy, if belated, intersection, a cello note that Clendinnen discerns in Montaigne: ‘It took some time for me to understand that this cheerful, sanguine man’s central preoccupation is with death and how we ought to meet it.’ These essays are all concerned with reckonings of one kind or another – with life, with death, and with the epistemological and ontological puzzling that precedes such reckoning. But Clendinnen’s puzzling has a particular intensity because she has had, as it were, two tries at life. Here is how she describes them at the beginning of Agamemnon’s Kiss: ‘A little over sixteen years ago my old life was ended by severe illness.’ Readers will know the details of that illness from her memoir, Tiger’s Eye (2000). Given ‘new life’ through surgical skill and the kindness of a liver donor, Clendinnen ‘felt like a hatchling escaped from its tight, white, silent world into this great, vivid, pulsing one’. The exhilaration, she notes, lasted for months. ‘Then I sobered (though not, I am happy to report, completely) and began, as they say, to consider my position.’

These two new books, then, are a distillation of Clendinnen’s reviewing of the situation after that pivot in her life. Like Fagin, she is full of ideas, some of them new, most of them the ripe fruit of an historian’s long-practised discipline, others coming out of the unexpected liberation that her ‘new life’ brought. Agamemnon’s Kiss is dedicated to her unknown donor, but also to Helen Daniel, one-time editor of ABR. It was Daniel who cajoled Clendinnen back into writing after illness had taken away her academic occupation. The result was an essay (‘Reading Mr Robinson’), in Australian history, a domain Clendinnen had previously ignored with some derisory gusto (boring, full of ‘dretful desarts’). But Clendinnen, an avid swimmer, makes the backflip a graceful exercise (would she were speechwriter to our rhetorically malnourished politicians). She has since written at length on Australian history in Dancing with Strangers (2003) and her Boyer Lectures (1999).

What these two new books mark is a shift, an expansion perhaps, into a different mode, but for Clendinnen a congenial one. She is a natural essayist – a ‘dolphin of the mind’, as poet and another natural essayist, Peter Steele, puts it. Even if she does claim to have learned late what an essay is (‘a direct, equal, personal communication on a matter of shared interest between writer and reader’), she has been tuning herself for the essay all her writing life. The interrogative temper of the form perfectly matches her method. And the necessary ‘I’ of the essay, the accountable author, the one with whom the reader feels licensed to dispute or agree, has always been there in Clendinnen’s writing. As a professional historian, she now exhibits no inhibitions about the ‘I’ (despite having been told by one senior academic that the use of the upright personal pronoun robbed her of all pretension to scholarship), and says so, with passion, in ‘Fellow Sufferers’, where she sifts the chaff from the wheat of historians’ methodology:

First, historians need to decide which among the accrued conventions of historical writing matter, and which are mere encrustations. We have learnt that God-historians hovering somewhere up above the texts extort no knee-bobs nowadays. We have to be ready to admit that a human hand pushes the pen or taps the keys of the word processor, that there is a needle ‘I’ between the past and the now through which everything must pass.

Clendinnen wants much from historians: she wants them to be writers who ‘rouse our imaginations, our critical intelligence (and our helpless envy) by the precision of their inferences, their moral and intellectual poise, and the exactitude and athleticism of their prose’. Such paragons exist: she cites E.P. Thompson and Peter Brown as two such. I remember reading Brown’s The Body and Society (1988) through sleepless nights with something akin to joy. A new old world, shimmering there in the prose.

The Quarterly Essay, Who Owns the Past?, makes related demands for history and of historians. Clendinnen finished it just days before she attended the History Summit called by the Federal Education Minister Julie Bishop. One can only hope, with Clendinnen, that some of her insights will be understood and her message heeded: ‘that there can be no purely “objective record of achievement” of anything as complicated as a nation’, and ‘that history’s social utility depends on it being cherished as a critical discipline, and not as a tempting source of gratifying tales.’

The essay itself provides an instructive model for the way in which history might be done in a nation which aspires to understand itself. Clendinnen is neither predictable nor boxable. Her ideas about Anzac Day would please the RSL. In the section where she takes issue with her colleague John Hirst (‘Morality in History: How Sorry Can We Be?’), we see how deftly argument can be deployed. I look forward to reading Hirst’s reply, not because I expect a skirmish that will become part of the ‘history wars’ but because argument in a civil society is not a weapon but a natural route to enlightenment.

In the cornucopia that is Agamemnon’s Kiss, we see Clendinnen the rigorous arguer alongside Clendinnen the anarchic young woman enjoying the unencumbered democracy of Australia’s mid-twentieth-century beaches. There are reviews (of Penelope Fitzgerald and Hilary Mantel) that morph into essays and make you ache to read both writers. There are feral whimsies like her hilarious neo-Luddite attack on technology (‘The Gecko in the Machine’). I am always reminded of Thomas Wyatt’s famous line (from ‘Who so list to hunt’), supposedly about Anne Boleyn, when I read Clendinnen: ‘Wylde for to hold, though I seme tame’. There is decorum, stringency and propriety in her writing, but don’t fool yourself that you could ever hold her. And ‘Cesar’s’ she has never been.

At the end of Tiger’s Eye, the writer, with a still-fragile sense of self, declared herself tired of introspection; ‘I am tired of the “I”, with its absurd pretensions to agency, so elegant, so upright, moving so serenely through the thicket of lesser words, surveying them from such a height. Poised on so narrow a base.’ Six years on, the base has firmed and broadened. The historian’s professional hoard has come to the aid of the ‘I’, and in a literary form that rejoices in the latitude Clendinnen would take anyway. Her understanding of Aztec ritual helps us comprehend the waste of wars we continue to prosecute, while still doing justice to the gallantry of warriors. She writes about early contact between Aborigines and settler Australians with scrupulous precision and – her own phrase – ‘an undertow of moral implication’ which a reader could well call wisdom. Quite simply, she has become indispensable.

Comments powered by CComment