- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Deflections of happiness

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Deflections of happiness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Battle of Crete began on the morning of 20 May 1941 with a new kind of warfare. German paratrooper battalions either parachuted or rode gliders down onto a defending force of British, ANZAC and Greek troops. The invasion took two weeks of bloody fighting to achieve its objectives. It was not, as Greek-Australian writer, Angelo Loukakis has his Australian soldier, Vic Stockton describe it: ‘For the Germans Crete had proved no more than an exercise.’ In fact, airborne invasion was not attempted again. Hitler’s thrust into the Soviet Union on June 22 was almost destabilised, and when the battle was over, 5000 Allied troops were abandoned to certain captivity on the southern coast near the town of Xora Sfakion.

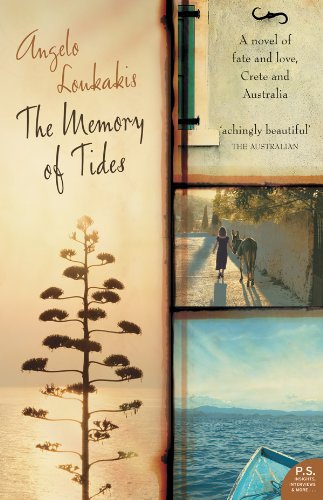

- Book 1 Title: The Memory of Tides

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins $32.99, 393 pp, 0732280672

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Among them is the fictional Stockton who is separated from the main column in the débâcle. Vic and his mate Stan, like many of the historical survivors, head across the White Mountains for the Libyan Sea. This dramatic opening initiates a pocketbook epic, a love story with the longest delay in consummation since Doctor Zhivago, and a rite of passage in which Stockton eventually discovers a homeland of sorts at the conclusion of the novel among the Cretan people, who, he realises, ‘were just as subject to their passions as he was’ – a propensity that has alienated him from his fellow Australians.

The structure of the novel is highly risky, a double helix in which the Vic’s postwar experiences back in Australia, trapped in a conventional marriage, reflects the development of his Cretan mentor Kalliope Venakis, a 21-year-old village girl when Vic first meets her, half starving and hopelessly lost outside her village. The plot appears to be of a well-trodden kind in which Vic and Kalliope are attracted to each other at the outset, and the reader is led to expect they will enjoy one of those passionate, doomed wartime affairs. However, they don’t meet again until they are both in their seventies, when Stockton returns to Crete on a mission of gratitude for his wartime experiences.

In the intervening decades (which Loukakis insists on giving us in minute detail), Vic stumbles blindly from failed developer to failed husband to eccentric farmer at Castle Hill. It is a life so banal in the telling that it risks the tone of Dame Edna’s deadpan mockery of ordinariness: ‘Baby Jennifer was born in August 1956, a bouncing seven-pound ten-ounce cherub. Vic and Joan were thrilled and took the precious bundle back to the little room they had set up for her.’

Potentially much more interesting is the portrait Loukakis paints of Kalliope. The epitome of all that is admirable about the Cretan people she joins the resistance against the Germans and then the Italians. But Loukakis’s sense of wartime Crete is all over the place. The tactically crucial airfield of Maleme did not fall to the Germans within a day, but after three days of fierce fighting. Kalliope’s village of Arkadi is nowhere near the southern coast, while the Italians were not permitted by their German masters to adventure further than the eastern end of the island.

Loukakis presents Kalliope with a potentially rich social milieu redolent of village life before the occupation. She is surrounded by carefully defined Cretan friends who reflect the political tensions of the period. Yet with the exception of her friend Marika who dies at the hands of an art-loving Italian officer – a contrived swipe at Louis de Bernières’ opera-loving Captain Corelli – none of these characters is developed. Kalliope’s husband, the increasingly banal expatriate Andreas, loses his politics and the best qualities of his Greekness as, with increasing desperation, he conforms to Australian values, a betrayal that alienates Kalliope during their attempt at married life in Sydney.

In many of his short story collections, such as For the Patriarch (1981) and Vernacular Dreams (1986), Loukakis explores the experience of diaspora. It is a perspective he shares with twentieth-century Greek novelists such as Pandelis Prevelakis, a nostalgia for a disappearing traditional culture within the melting pot of the migrant experience. Kalliope measures expatriatism against what has been lost. At her own wedding banquet, she observes that ‘it all seemed so pathetic somehow’ in comparison with village practices and, when she finally quits Andreas and Australia, it is defined as ‘a life that she no longer wished to waste any time on’. Given the banality of the prose and the narrative, the reader is not surprised. It is a response shared by Vic, her spiritual mate, but both Patrick White and George Johnston have shown how to criticise the cultural and social underpinnings of Australian life while giving them interesting depth.

What does slowly emerge from Loukakis’s novel is the theme of a painful nostalgia for a lost homeland in which diaspora foreshadows alienating change. The narrative leaves a hiatus for sentimentality in the deflections of its frustratingly anticlimactic love story. But it explores the idea that if history is indifferent to the destinies of individuals, lovers are tied together by the shared experience of a coherent community that finally and triumphantly erases all deflections of happiness.

Comments powered by CComment