- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Under the frangipani tree

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Under the frangipani tree

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Australian soap Neighbours maintains its popularity overseas. Busloads of UK tourists bound for Vermont South attest to this. The soap’s popularity lies in its reflection of the domestic and the mundane. It provides a safe means for overseas viewers to explore the exotic: the trials of the Ramsay Street clan are not so different from their own. Soon, thanks to author Célestine Hitiura Vaite, Tahiti may have its own busloads of tourists, searching for the petrol station in Faa´a PK55, location and setting for the domestic, everyday dramas of Breadfruit, Frangipani and Tiare.

- Book 1 Title: Breadfruit

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $22.95 pb, 339 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

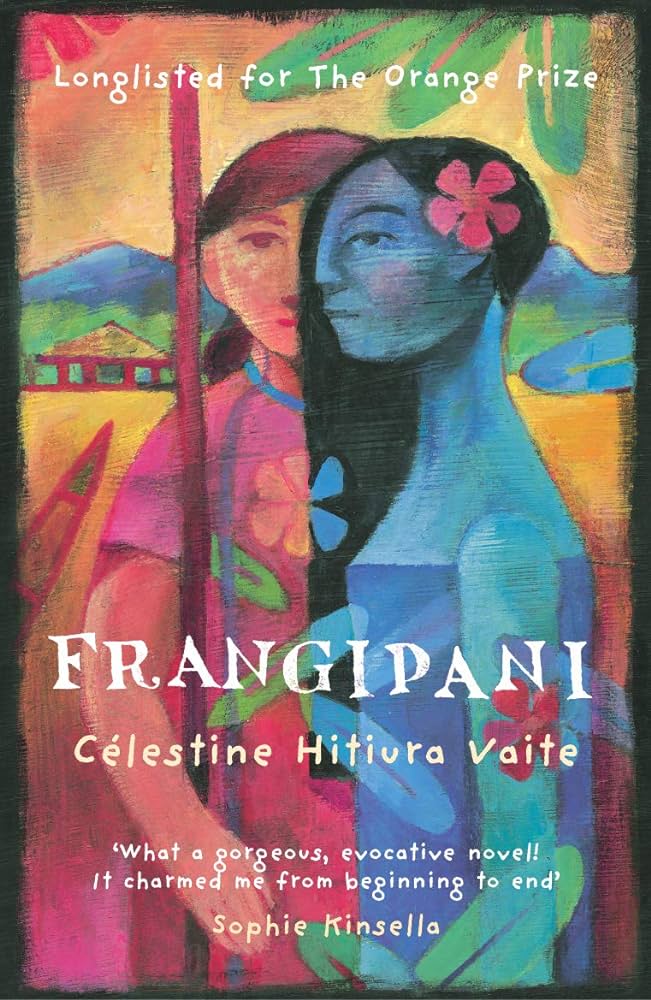

- Book 2 Title: Frangipani

- Book 2 Biblio: Text, $22.95 pb, 295 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

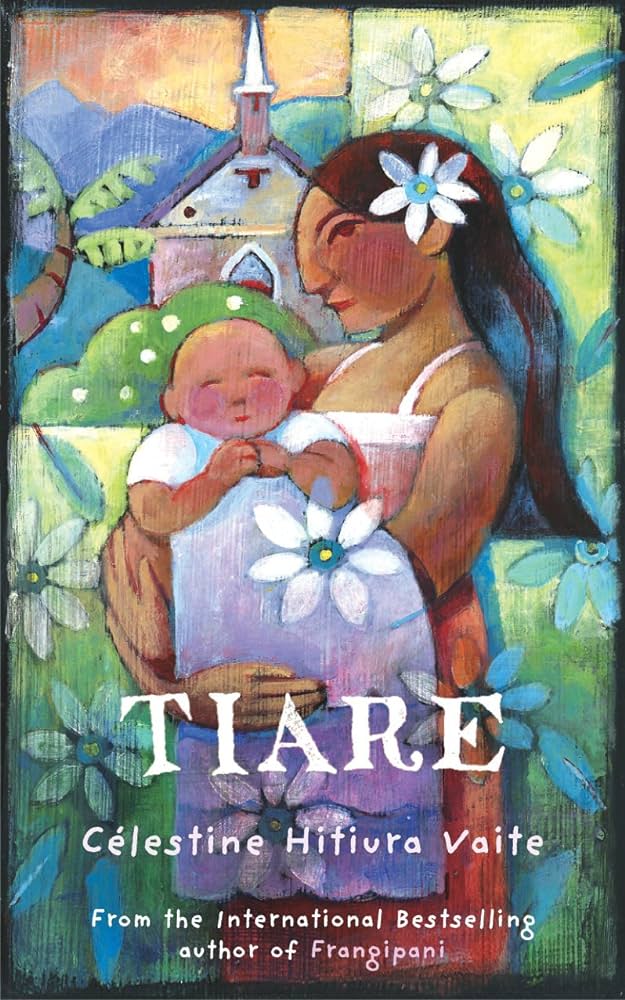

- Book 3 Title: Tiare

- Book 3 Biblio: Text, $29.95 pb, 250 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is unfortunate that most readers will commence the trilogy with the first, Breadfruit, for it will alienate some of them. The cover quotes a review: ‘Fresh, honest, and warmly funny. I just couldn’t put it down.’ Quite frankly, I found it hard to pick up after the first few chapters, mostly due to the storyline of Matarena’s quest for marriage to the detestable Pito, father to her three children. Pito staggers drunk into the house one evening (not an unusual occurrence), slurs a wedding proposal and is fast asleep within five minutes. Naturally, Pito forgets his proposal the next day – but not so Matarena. Breadfruit tells the story of her secret arrangements for this wedding, but it is often hard to see why she wants to marry such a man. When she presents Pito with the carefully chosen birthday gift of a colourful shirt, he tells her that he ‘is never going to wear that shirt, not even for cent mille francs’. Another time, displeased that Matarena has taken too long to return from the store with his favourite hangover cure, Pito cries ‘Did you go to France for that lemonade?’

Vaite has admitted that Breadfruit began life as a collection of short stories, some of which were submitted to an Australian publisher. The publisher wanted a novel, not those pesky short stories that publishers are always complaining about. In an interview with The Age, Vaite said: ‘[Breadfruit] was the hardest book to write because I had forty stories on the floor … and I was thinking, I’ll put this here, and here. It was a nightmare.’ The novel does indeed read like a collection of stories, loosely held together by the marriage quest. Some of them are charming. There is the wonderful story of Pito’s best friend, Ati, and his desire for Tahitian independence, in which Matarena’s mama questions him about who cooks and cleans for him. He doesn’t have a wife, so (of course) it is his mother. ‘Independence, my arse,’ declares Mama Loana. There are the endearing heroics of Mama Teta’s driving lessons, and the familiar battle between mother and daughter-in-law over who has the biggest frypan, all of which win the reader’s empathy.

It is when exploring specifically Tahitian issues – independence, the relationship with France, local legends – that Vaite’s writing becomes compelling, the stories vivid. Such details open the reader’s eyes to Tahiti, not as a glamorous tourist destination but as the result of European colonisation. The reader cannot help but sympathise with Materena’s fear of the gendarmes, her loss of Pito to military service in France and the poignant story of the colonisation of Tahitian language in the chapter ‘Teacher’. Here, Matarena recalls it being ‘forbidden to speak Tahitian in the school grounds … the (French) nuns pacing the school ground, their ears open for a foreign word’. Foreign, indeed, but not for Matarena. Throughout Breadfruit, however, there are also banal stories and language. The conversation between Matarena and cousin Tapeta is lacklustre: ‘Are you going to do some shopping?’ ‘Oui, just a couple of things.’ ‘Ah me too. A few corned beef cans, toilet paper, soap.’ ‘And how are the kids?’

The second of the trilogy, Frangipani, is essentially a mother–daughter relationship novel and tells the story of Matarena’s troubled relationship with her teenage daughter Leilani. The novel opens with a chapter, ‘The Day You Came to Me’, in which Matarena is still shackled to the wayward Pito, who has now left her because she picked up his pay packet rather than have him drink the proceeds at the pub. She declares Pito ‘the king of the sexy loving’, and recalls a much earlier sexual encounter ‘under the frangipani tree’. It was under that frangipani tree that her first child was conceived and, now, after a more recent night with Pito, she finds herself pregnant with her second child – and husbandless. The story leaps forward twelve years: Leilani is a feisty, independent, modern Tahitian girl. The chapter title ‘We’re a Different Generation’ encapsulates Leilani’s journey as she tries to define herself in contrast to her mother (a professional cleaner), using education and gender equality as her platforms for future freedom. But each woman carves out her own place in Tahitian life, and must come to terms with all of the similarities (their shared passion for Tahitian men and ‘sexy loving’) and the differences between them.

Tiare – the third, and most engrossing, novel in the trilogy – tells the story of Matarena’s granddaughter, born after a Parisian night of passion between her son and a Tahitian dancer, and subsequently abandoned on Matarena and Pito’s doorstep. Pito plays a major part in Tiare, where the author sets out to redeem him. With a granddaughter delivered into his arms, the previously selfish and chauvinistic Pito finally becomes the father Matarena has always wanted him to be: sensitive, responsive and engaged with parenthood. After the two previous novels, and Pito’s obdurate behaviour, it is hard for the reader to believe in his mammoth personal transformation. Indeed, Vaite’s characterisation of Matarena as an amiable and honest heroine, to be admired and loved, is undermined by her weakness for Pito. But the reader can still cheer for her. Matarena, who warned her daughter against becoming ‘a nobody like me’ in Frangipani, has now risen to become a talk-back radio star.

These three novels are each adorned with a big black sticker on their covers: ‘If you liked McCall Smith you’ll love Célestine’. Alexander McCall Smith has said that he aimed to show the ‘small, everyday Botswana that the tourist doesn’t see’ in his best-selling series, ‘The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency’. In this way, the comparison is apt, as Vaite, too, reveals everyday life in an exotic locale, far from the tourist eye. However, McCall Smith is a master of both language and moral concerns. I doubt that he would have his characters cackle lines of dialogue ‘like crows’ or would repeat the phrase on one page (indeed, a dozen times in one novel). He has also said that ‘for a novelist to portray goodness and innocence without preaching into sentimentality is difficult’. Vaite often falls into this trap: for example, in the ‘welcome to womanhood’ talk Matarena gives Leilani in Frangipani.

What is missing in Vaite’s trilogy (and what makes the McCall Smith comparison less than apt) is reflection on the everyday. While there is much here that entertains, much that may correspond to the reader’s own daily experience, I yearned for McCall Smith’s illumination of the mundane.

Comments powered by CComment