- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Flagrant act of word-spreading

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Flagrant act of word-spreading

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In Alice Pung’s memoir of her childhood, Unpolished Gem, her young self is drawn into a conflict between her mother and grandmother, both Chinese-Cambodian refugees. The child becomes a double agent, informing each about the other, until her mother accuses her of ‘word-spreading’ and threatens suicide. The child frets over her breakfast: ‘I always spread my jam on toast all the way to the very edges – no millimetre of bread is left blank and uncovered. My word-spreading habits are similar.’

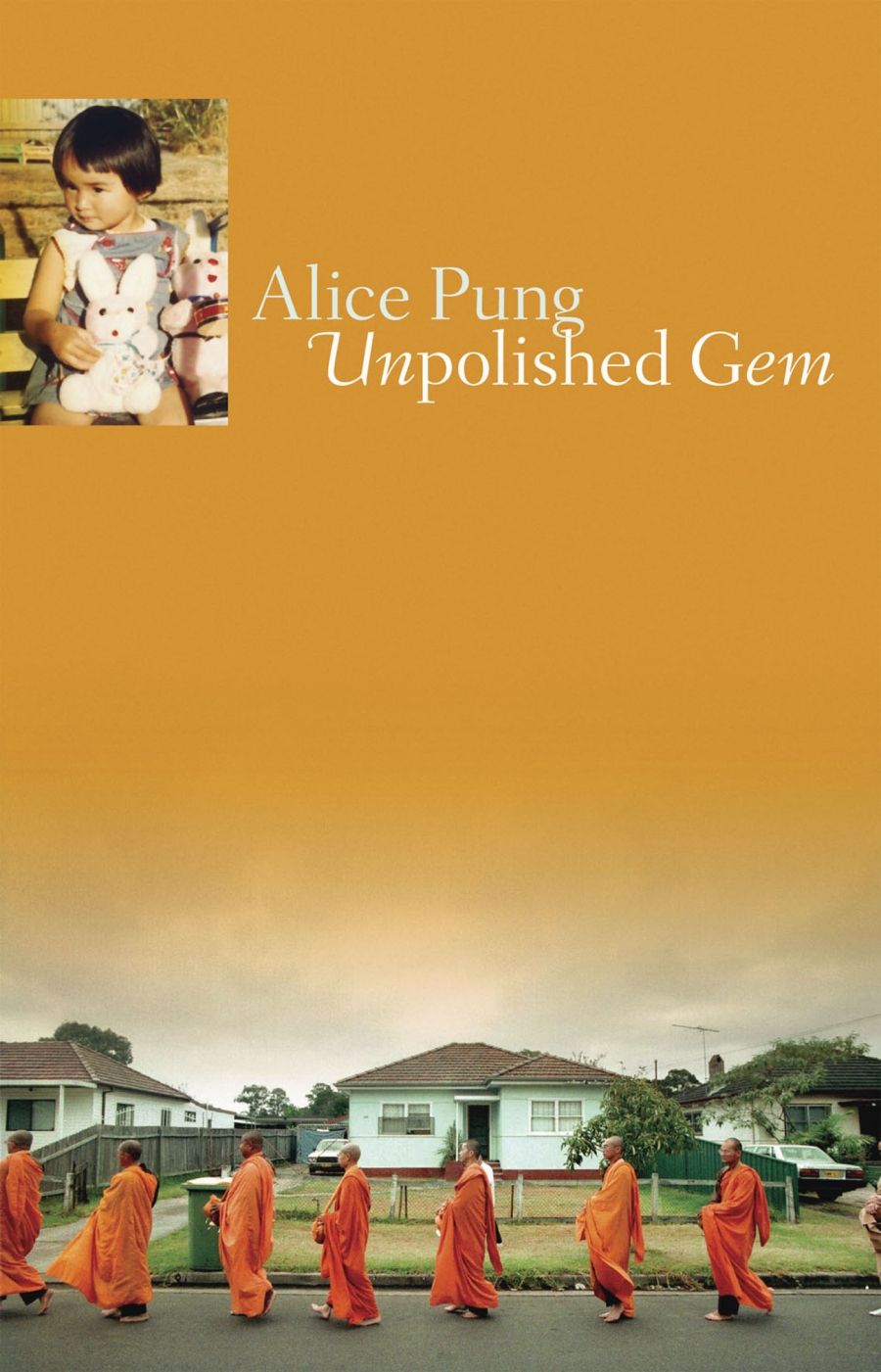

- Book 1 Title: Unpolished Gem

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $24.95 pb, 282 pp, 186395158X

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

.jpg)

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

.jpg)

Unpolished Gem is a flagrant act of word-spreading. Pung spares herself nothing: incontinence, depression, head lice, medication, thwarted love. It is an affectionate book, full of delicious observation, but demands much more from the reader than fond condescension. The bright colours turn out to be lures, as Pung delivers a bracing dose of reality.

Pung’s childhood role as double agent prefigures the central quest of the book: her search for identity, caught between her Chinese heritage and Australian environment. Her easy, colloquial voice has an ocker accent, and a distinctive rhythm that perhaps stems from the Teochow dialect of her childhood. Occasionally there is a clumsiness in the cultural transfer. To Australian ears the book’s title might sound immodest, but it refers to a Cambodian saying about a woman’s virtue, a key theme in the book: ‘A girl is like white cotton wool – once dirtied, it can never be clean again. A boy is like a gem – the more you polish it, the brighter it shines.’

Pung structures her story as a series of coming-of-age episodes in Footscray, set in counterpoint against her family’s Cambodian past. But even in Footscray, Cambodia is never far away:

My father’s idea of getting familiar with someone was to tell them war stories. He didn’t do it to sober them up or edify them. He did it to crack them up.

‘This fish reminds me of the Pol Pot years when the starved, dead bodies floated up the river during the flood ...’

Despite this bleak backdrop, the real grimness of the book is in the immigrant experience. In Pung’s telling, it is the women who suffer the most: desperation runs like a bloodline through the female characters. She has a special tenderness for her grandmother, who pampers her as a child, and reveres the benevolent ‘Father Government’ of the new country. However, after a stroke, her grandmother spends much of the story supine, ‘crying like a cat, tearlessly but loudly’. At her school, Pung unwittingly cracks a joke at her grandmother’s expense, and then joins in the laughter. Her relationship with her mother is more problematic, and their generational gap is deepened by language. While her mother struggles to learn English, Pung finds herself ‘running out of words’ in Teochow. Her mother labours as an outworker; when she no longer needs to work, because of her husband’s success, she no longer knows herself. Pung paints a bleak portrait of her mother’s depression, and that of a generation of Asian women, sitting in their ‘double-storey brick-veneer houses’, paralysed by luxury. It is a Feminine Mystique suburban nightmare, made more claustrophobic by language.

Pung rejects the model of Chinese womanhood she has been served (‘constantly sighing and lying and dying – that is what being a Chinese woman means, and I want nothing to do with it’), but struggles to find an alternative. She spends her adolescence under a sort of house arrest, protected from real and imagined dangers, not least that of young men: ‘I imagined myself wasting away like a princess in a tower, or rather a caffeine addict in a shack behind the Invicta carpet factory.’ Like her mother, she finds herself through compulsive industry: ‘for me there was housework, and then there was homework to alleviate the boredom of the housework.’

But industry can only take you so far, and it is too much industry that leads to Pung’s breakdown at the end of her school years. Again, this could be any good girl’s overachieving nightmare, but with Pung’s background, the stakes are higher. One of the book’s most poignant observations occurs during this breakdown, at Pung’s high school valedictory dinner:

That night our parents realised something that probably shook them from their sleeping dream, the semi-dazed dream they entered when they rested from too many taxi-shifts, or when they closed their eyes from the fatigue of opening too many stitched buttonholes. They realised that their children were Watchers, just as they were.

The position of Watcher or outsider might be a painful one, but it serves the writer well. Pung’s position as a ‘permanent exchange student’ offers her a unique perspective. She is able to see in double: the University of Melbourne, where she later studies Law, is ‘Mao-Bin U’ to her parents, which she imagines as a ‘shonky university in China for discarded communists’. Her double vision is at its keenest during her relationship with an Australian boy, which ultimately proves too culturally freighted. She delicately explores her family’s ambivalence towards ‘white ghosts’, while imagining herself into his head: ‘You’re his third-world trip or something. He’s too broke to go overseas so you’re his substitute exotic experience.’

There is no real sense of resolution at the story’s end; probably there shouldn’t be for one so young. Instead, the writing of this book seems to be its unspoken conclusion. It is through writing that Pung finds her identity, and her identity is word-spreader. As a word-spreader, she is indeed a gem: startling, beautiful and fierce.

Comments powered by CComment