- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Custom Article Title: How wrong they were

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: How wrong they were

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The subject of fear and politics has often captured the attention of the political left. Indeed, I am immediately reminded of two wonderful books: In Place of Fear (1952), by the British Labour politician Nye Bevan; and The Fear of Freedom (1941), by the post-Freudian and socialist Erich Fromm. Whilst Fromm set out to understand the roots of fear in the human condition, Bevan sought practical solutions to the most obvious manifestations of fear in a world that had been shaken to its foundations by economic depression, fascism and war. Both were democratic socialists who believed that the insecurities which led to fear could be tackled through political, social and economic change.

For a brief moment following the collapse of communism, it appeared that such a solution might be within our grasp. Some even talked of ‘the end of history’. How wrong they were, as we witness the rebirth of insecurity associated with global warming, international terrorism and nuclear proliferation.

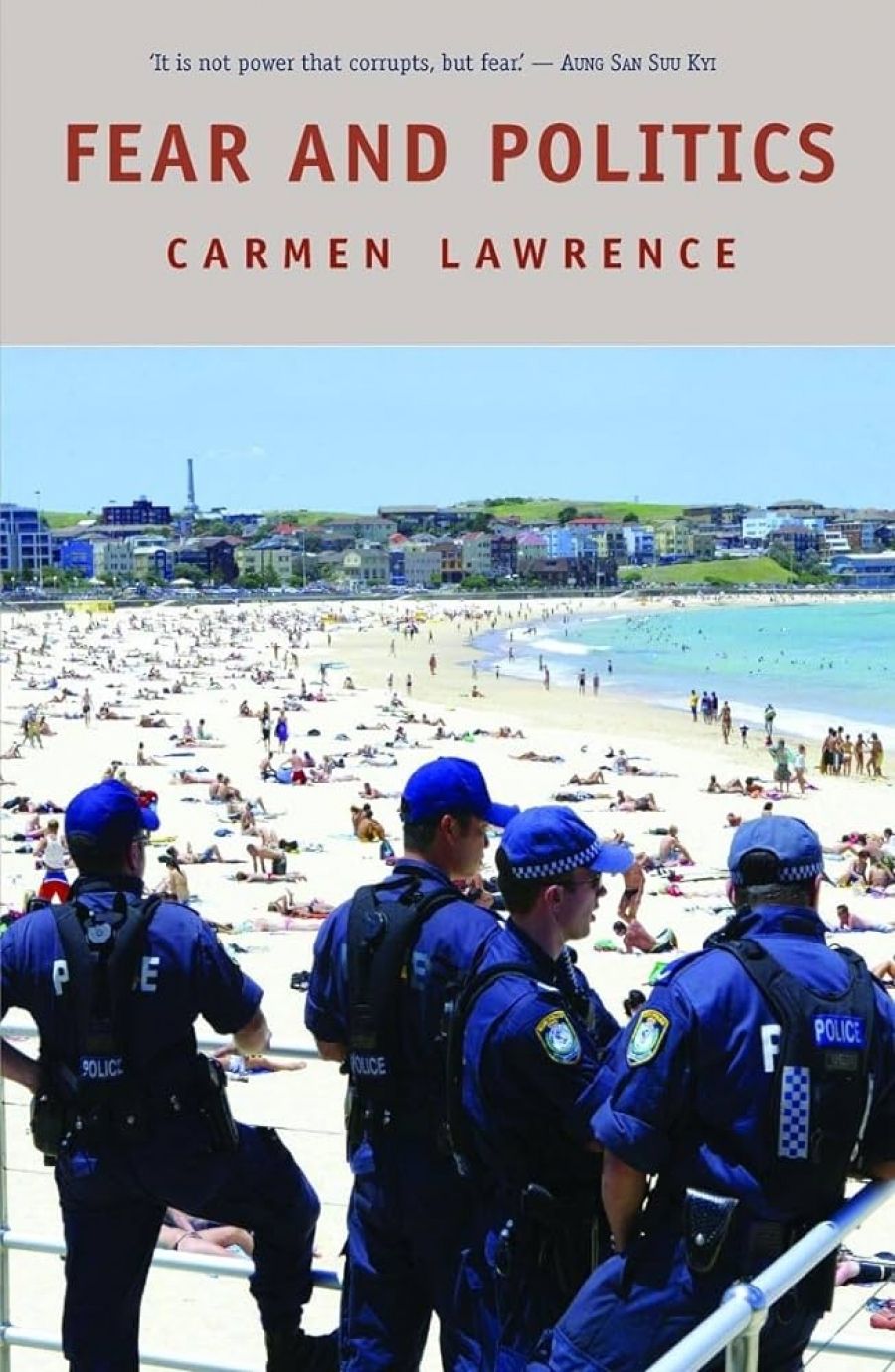

- Book 1 Title: Fear and Politics

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $22 pb, 136 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is to this world that Carmen Lawrence turns her attention in Fear and Politics. Her primary interest lies with Australia and what has happened to the culture and practice of politics in the last twenty years, but most particularly with the Howard years.

Lawrence situates her account of contemporary politics within an analysis of the place of fear in the human condition. Fear is seen as necessary to survival in that ‘it acts as an alarm to indicate the presence of a threat and to stimulate us to save ourselves from injury or death’. Unlike other animals, however, human beings know what it is they are most afraid of — death. To manage this anxiety they develop belief systems about the meaning of life and their place within the universe. They gain comfort from the fact that these views are shared by others, and in some cases incorporate a belief in life after death.

What is crucial to Lawrence’s account of contemporary politics is the next step in her argument. She refers to numerous studies which show that when people are reminded of their mortality ‘they are more likely to exhibit increased prejudice and aggression towards those who question their beliefs, those with different world views, and those who are, or appear to be, different from them’. The implication she draws from this is straightforward: a culture of fear creates a society of division and conflict from which there is no escape.

Lawrence acknowledges that there are many things that may cause us to have legitimate fears. However, it is her view that some fears are ‘rational’ and some are ‘irrational’. As best as I can determine from her analysis, rational fears are those that are based on fact and are most likely to be realised. Irrational fears, on the other hand, are either not based on fact or are most unlikely to be realised.

Her primary targets are the politicians and media who exaggerate fears and promote insecurity in relation to crime, disease, terrorism, Aboriginal land rights and immigration. In order to prove her point, she uses statistical analysis. She refers, for example, to the gap between the probability of being a victim of crime and public perceptions of crime, the improved standards of health and well-being, the small numbers of people actually affected by terrorism, the limited likelihood of native title impacting on existing rights and the small numbers of refugees actually coming to Australia.

What concerns Lawrence is that governments throughout Australia have used irrational fears to justify laws and policies that do threaten freedom but which are ineffective and/or counterproductive in relation to the matters they are intended to address. She is scathing of the ‘tough on crime’ and ‘tough on terror’ measures of the Commonwealth and State governments.

It is at this point that Lawrence’s argument begins to look shaky. For many communities throughout the nation, crime and anti-social behaviour are ever-present realities demanding attention. In these communities, the probabilities will be somewhat different than in the state or nation as a whole. I would also question Lawrence’s conclusion that State governments have been preoccupied with ‘tough on crime’ policies at the expense of ‘tough on the causes of crime’ policies. Indeed, it has been a feature of the state Labor governments that they have invested in programmes designed to tackle the circumstances that lead people to crime.

In respect to terrorism, Lawrence is equally scathing about Commonwealth and state responses. She questions the very idea of a ‘war on terror’. Certainly, it is not a war in the conventional sense, and some of the strategies adopted to deal with it have been less than defensible, let alone effective. In the case of Iraq, they have been disastrous. However, the fact remains that a particularly nasty form of Islamic fanaticism does pose a threat to our citizens — and others — even if not to our national sovereignty. Governments have a responsibility to take steps to prevent terrorist acts on Australian soil and to properly plan for such a contingency. The responses should be relevant to the task at hand and not simply motivated by hatred and revenge; but to argue, as Lawrence implies, that the ‘war on terror’ is little more than a case study in irrational fear is to misjudge a significant new develop-ment in world politics to which that ‘war’ is responding.

Viewing modern politics through the prism of fear provides us with many insights. It encourages us to be serious about risk assessment and risk management, but it always needs to involve more than an analysis of probability, which by its very nature cannot deal with a rapidly changing world. Lawrence is correct, however, in pointing out that fanning the flames of fear can have dangerous consequences, not only in societies with a history of prejudice but also in any community containing differences based on race, religion and ethnicity. Political and community leaders have a special responsibility in this respect and should repudiate ‘hateful and aggressive language’.

This takes us to the second part of her argument: the use of threat to make people fearful and therefore compliant. She notes that among the very justifications of democracy, used by Sir Robert Menzies among others, is that it removes the fears associated with tyrannies and authoritarian governments: ‘One of the strongest motives for adopting democracy as a system of government is people’s desire to be protected from … state-sponsored fear.’ Lawrence goes straight for the jugular and accuses the Commonwealth government — aided and abetted by the ‘culture of Canberra’ — of stifling proper consideration and debate about public policy, and threatening and intimidating those who would dare to question its policies and priorities. She draws our attention not just to systematic efforts to suppress information about the workings of government departments and contracted agencies, but also to the attempted micro-management of State governments on the basis of Commonwealth funding. Hers is a story of attempted control and compliance: of individual to State; of employee to employer; of public servant to minister; of parliament to the Executive; of State government to Commonwealth government; and of non-government organisations to government.

It is as if the Howard government has been contaminated by the very fears about which it so often speaks in respect of the nation’s sovereignty, seen as under attack from refugees, terrorists and Aboriginal land claims. Interestingly, though, Lawrence speaks less of the government in terms of the ‘psychology of power’ and more in terms of the ‘utility of power’. This despite the fact that in the first chapter she refers to research about the link between political conservatism and authoritarianism. The research shows ‘higher levels of fear about threat, loss, death, and social breakdown’ and a desire for ‘order, structure, and closure’ among political conservatives. This raises the issue as to whether the promotion of fear and the use of threats is more a manifestation of deeply held beliefs rather than the cynical manipulation of power.

In many ways, the fears we have define who we are and what our priorities are. The problem for those who share Lawrence’s politics is not so much that we are a society of ‘nervous Nellies’ but that the conservatives have been able to place their definitions at the centre of the national agenda. What we are seeing now, however, is that the union/Labor campaign on the new labour relations laws is shifting a new set of fears onto that agenda. What seemed to be a political closed shop at the national level is beginning to fray around the edges. Ironically, John Howard will be using a Carmen Lawrence-like ‘fear’ argument to combat his critics and to defend his changes.

This is a book that will make you think seriously about the relationship between ends and means in politics. However, its approach is too limited — and questionable in respect of its treatment of crime and terrorism — to provide a basis for a political renewal of Labor.

Comments powered by CComment