- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘We are all little Johnnies now’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The provenance of The Howard Factor – a collection of essays by senior writers from The Australian newspaper – is not promising. The Australian is after all part of Mark Latham’s ‘Evil Empire’, cheerleader rather than critic of the Howard government. Yet its sympathy for the régime stems not from partisanship but from the newspaper’s philosophy: neo-liberal in domestic matters, neo-conservative in foreign policy. Populist desertion of elements of the neo-liberal agenda has aroused the wrath of the newspaper: witness its condemnation of the government’s policy funk in early 2001, and of its recent surrender to Snowy River romanticism. Discord has been less in foreign policy, where both government and newspaper have been willing recruits to the ‘war on terror’. So slavish has become the newspaper’s adherence to America’s contemporary wars that it has even repudiated its quite heroic stance on the Vietnam War a generation ago.

- Book 1 Title: The Howard Factor

- Book 1 Subtitle: A decade that transformed the nation

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $29.95 pb, 349 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

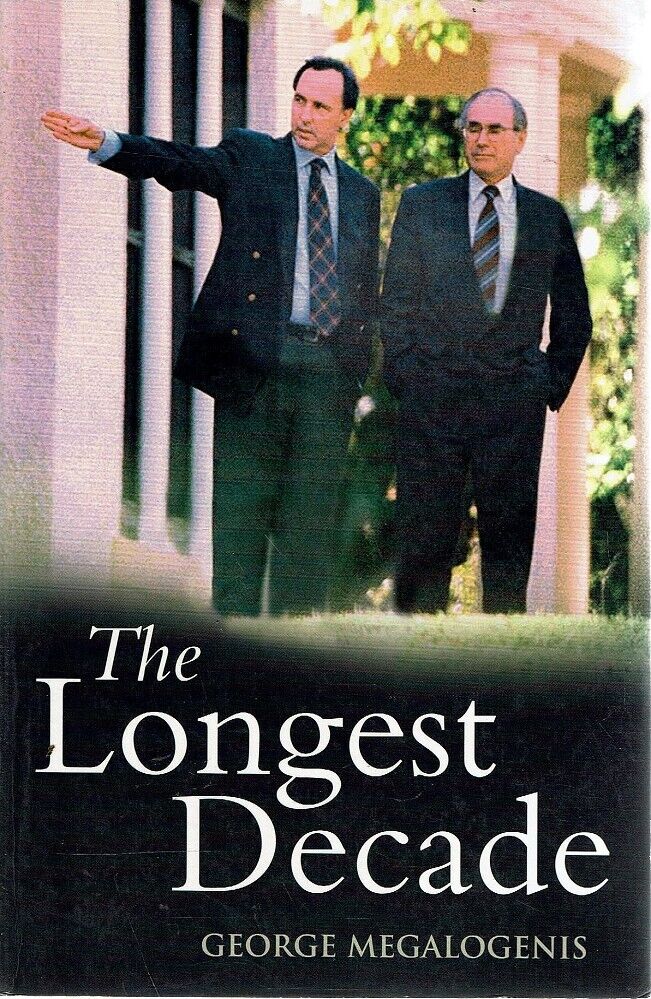

- Book 2 Title: The Longest Decade

- Book 2 Biblio: Scribe, $32.95 pb, 346 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The impressionistic immediacy of journalism can be a handicap. We require more from a book than recycled newspaper columns. This problem has been exacerbated by odd editorial decisions. Few of the writers are given more than ten pages to develop their arguments, and yet one hundred pages are put aside for a chronology of the Howard years, a useful research tool which could have been compressed into one-third of the space. The contrast is with a rival book, Robert Manne’s The Howard Years (2003), in which roughly half as many contributors get an extra hundred pages to develop their arguments.

As a result, much of the material is easily dismissable, reading like reheated columns, mostly short and insubstantial, frequently triumphalist, occasionally amusing and inevitably ephemeral. Why zip around all over the place with Christopher Pearson in pursuit of the Zeitgeist or devote space to Matt Price’s piece on the Howard persona, which, like an Alan Ramsay column, is stuffed full of other people’s words? Kate Legge seeks valiantly to persuade us with anecdotes from Howard friends that Howard has never been ‘the patron saint of the stay-at-home-mum’. Samantha Maiden regurgitates the propaganda of choice in education and health, but does not probe beneath the superficialities, and concludes that ‘Howard has trip-wired the political agenda’. Trip wires or not, the pouring of money into both Medicare and private health insurance will end in fiscal tears. Steve Lewis has a rather pedestrian piece on the black farce of Labor in Opposition, without any reference to Latham’s vituperative critique of his own party. Perhaps all references to The Latham Diaries (2005) are verboten within the ‘Evil Empire’? (As there is no index, I have not been able to check this.) Bill Leak has great fun tracing the evolution of Howard as a simian cartoon character concluding sardonically that ‘we are all little Johnnies now … looking more like monkeys every day’.

At the core of The Howard Factor, however, are some essays that make a formidable case for Howard as a formidable prime minister. Dennis Shanahan’s claim that Howard is ‘Australia’s most successful Prime Minister’, while debatable, is no longer risible. These contributions focus on Howard: his style of governance, his character and personality, correctly so since, unlike his immediate predecessors, Howard is the government. Howard’s has not been a ministry of all the talents, for his ministers have been a lacklustre lot. Of his original cabinet, all but four have gone; and with the exception of Tim Fischer, they have departed un-lamented, their mishaps ironically enhancing the undoubted competence of the prime minister. Nor, despite Peter Costello’s contribution to economic management, is Howard’s government ever likely to be known as a hyphenated government in the manner of the ‘Hawke–Keating government’. Howard is both an astute political manager and the dominant ideologue within the cabinet. In this sense, he is both Hawke and Keating.

These writers rightly stress complexity, rejecting simplistic dichotomies of Howard as ideologue or pragmatist, conservative or radical, principled or populist, idealist or opportunist. Paul Kelly sees him as a radical populist and a Burkean conservative; Glenn Milne as radical on market economics but conservative on moral values. Following Milne, but with a more specific policy orientation, we can see Howard as an ideologue on industrial relations; an idealist on gun laws; a populist on Tampa; a man of principle (even if one doesn’t like the principles) on Iraq; an opportunist on Pauline Hanson; a pragmatist on Medicare; a conservative on gay marriage; a radical on federalism.

In the best essay in the collection, Kelly shows how Howard has exploited the inherent powers of his office and created new ones so that an even more protean figure emerges. He is prime minister; de facto head of state, present at the aftermath of every tragedy from Port Arthur to Bali; talk-back media personality (‘he spends more time on the media than he does in the parliament or cabinet’); permanent campaigner (‘the most domestically travelled Prime Minister in the nation’s history’); economic manager; and, since 2001, security supremo. Under Howard, the politicisation of the public service, the decay of ministerial accountability, the triumph of the executive over the parliament, the expansion of the private office, the bullying of the judiciary have proceeded apace. None of this is novel; what is perhaps radical is its extent.

When did this Lazarus rise? During his second stint as Opposition Leader, suggest Shanahan and Milne, when he ceased to be a policy wonk and became a small target with no ideological angles at all. Milne also has a bet on the Port Arthur massacre, when Howard’s response indicated that ‘he was an emerging leader instinctively in tune with the national mood’. He notes, too, as others do, that the near-death experience in the election of 1998 ‘tempered the Howard steel’. Nicholas Rothwell opts for the Hanson challenge and Tampa: ‘Since then, the Prime Minister has converted himself into a kind of patriotic father figure.’

These key essays are supplemented by policy studies. Generally positive yet balanced, through them runs a strain of criticism. Alan Wood enthuses over the economic ‘golden years’, but adds a note of disappointment: ‘[A]nyone remembering the Howard … of the 1980s would have expected more in March 1996 than he has achieved over the past decade.’ Brad Norington traces Howard’s long-term commitment to industrial relations reform, but concludes that his final changes ‘all ran in the employer’s favour’, in whose ‘benevolence’ Howard has ‘placed [his] faith’, and perhaps his fate. Stuart Rintoul provides a competent defence of ‘practical reconciliation’, but admits that after ten years there is still little on the ground to show for it. Mike Steketee records that, despite the fall in unemployment, welfare spending as a proportion of government spending is greater than in Keating’s last year as prime minister, the result primarily of a massive expansion of middle-class welfare, which has created ‘a two-tier system’.

Neo-conservatives are given to hyperbole, and Greg Sheridan does not disappoint in his claim that Howard has ‘revolutionised Australian foreign policy’. It is probably true that Howard has achieved ‘an unprecedented intimacy with Washington’, but the United States alliance has been the bedrock of Australian foreign policy since 1941. We followed the United States into Vietnam in the 1960s; we were among the first to rally to the cause in the first Iraq War; not to have gone to Afghanistan or the second Iraq War would have been the revolutionary stance. Relations were strengthened with South-East Asia as a result of the Asian economic crisis, but again Howard was following in well-trodden footsteps. How is the relationship with Indonesia ‘an outstanding turnaround from 1996’? It seems today much the same as always – never easy and never likely to be easy. Howard has done a good job with China, but in much the same way as every prime minister since Gough Whitlam – namely, building a constructive relationship with the Chinese, but not at the expense of other foreign commitments.

George Megalogenis, from the same stable, has three short contributions in The Howard Factor, and offers another perspective on Howard in The Longest Decade. Megalogenis is an unusual political journalist, more interested in policy than process, always seeking to support his generalisations with hard data. In a style more hip than mandarin, he sets out to explore the contributions of both Keating and Howard to Australia’s contemporary economic success and to the nation’s sense of itself, his canvas roughly the period from 1990 to 2005. Rejecting as ‘inherently absurd’ the notion that one must be either ‘a member of the Keating fan club’ or ‘a Howard hugger’, he has produced a balanced assessment. In this he has been much helped by generous interviews with both Keating and Howard.

Alan Wood notes that many of the foundations of our current prosperity had been laid by Keating and Hawke. Megalogenis is more explicit, identifying ‘the recession we had to have’ in 1992 as the crucial event. Keating’s recession drained inflation from the Australian economy, but in the process destroyed its accidental creator. The slow and jobless recovery undermined the second Keating government, bringing with it the politically disastrous 1993 budget, the failure to honour tax pledges, and the three interest rate rises in 1994 which made Keating ‘unelectable’. Absorbed in identity issues and the woes of Carmen Lawrence, Keating went down to defeat, an event that seems to Megalogenis, if not to Keating himself, overdetermined.

Megalogenis, too, is fascinated by Howard’s meta-morphosis. He believes that Howard is at his best in times of crisis because ‘it is only when he is confronted with his political mortality that he has to think as the electorate does, free of ideology’. Megalogenis goes along with the crowd in seeing Howard’s fifteen months in his second stint as Opposition Leader as critical. In that period, Howard ‘had to beat up on his former self … and [learn] to conceal the bits of his political character that the public didn’t like’. He ‘aped’ most of Keating’s economic announcements and made his ‘never ever’ pledge about the GST, leaving Keating to complain, ‘[Howard] needed to say he was me to win [and I didn’t have time to] show he was not me’. But Howard’s strategy was not simply a case of ‘me too’. While Howard was determined to avoid Hewson’s mistake of seeking to out-flank Labor to the right on economic policy and thereby terrify the electorate, he was happy to fight on cultural policies. For Howard, this had two advantages: he believed that he could win the cultural battle, but also that his plea for the restoration of old Australian values might suggest for many the possibility of dismantling ‘un-Australian’ aspects of Keating’s disliked economic agenda.

Howard’s first honeymoon as prime minister was short because it was sustained only by the fact that he was not Keating and by his ‘gut call’ on firearms after Port Arthur. ‘Guns,’ says Keating grudgingly, ‘I’ll give him guns.’ The honeymoon was soon ended by the very nature of Howard’s electoral triumph. Megalogenis, no respecter of persons, sees 1996 as ‘pitt[ing] the two politicians who had told, between them, the generation’s biggest whoppers’ in a ‘me too’ campaign with ‘an in-built bias towards profligacy’. As a result, Howard could not honour his electoral promises, so we got the notorious concept of the ‘core’ promise, with its implicit denial of the ‘non-core’ promises. Howard was no better than Keating.

Moreover, Howard’s 1996 campaign ‘was a plan to win an election, not to run the country. By minimising the differences [with Keating], Howard had denied himself a man-date of his own.’ Into this vacuum were sucked damaging issues such as Wik and Pauline Hanson. Howard confesses to mishandling Wik; and while his treatment of Hanson was controversial, he had a better sense than most that Hanson encapsulated the powerlessness of the victims of rapid economic change, and he recognised her vulnerability. ‘You really had to hold your nerve and let her blow herself out.’ Contrary to received wisdom, Megalogenis thinks that these race debates damaged Howard in the short run because ‘the national dialogue had become toxic on his watch’.

Paradoxically, Howard’s recovery began with another broken promise: the decision to revive the GST. Megalogenis agrees with Howard that the decision to recommit himself to the GST was ‘a net plus’ in the near-death 1998 election: ‘Howard was saved because he had something to sell.’ Moreover, by 1998 Keating’s promise was at last being redeemed: the economy was ‘going gangbusters’ and the government would soon have at its disposal resources undreamt-of by previous governments. From Megalogenis’s sophisticated discussion of the dispersal of these resources emerges the question as to whether these moneys are being spent in the best long-term interests of the nation or in the short-term electoral interests of the Coalition.

Megalogenis locates the coming of Howard’s second honeymoon – the Howard Hegemony – in the fortnight between Tampa and 11 September 2001. While Tampa ‘helped the Hansonites come back home to the coalition’, Megalogenis believes, on the basis of his economic analysis, that Howard ‘would have won without it’. The over-55s had been bought with budget largesse in the 2001 budget; the aspirationals Labor had lost in 1998 remained lost in 2001 for strictly economic reasons; young families had been won with a doubling of the first home owner grant. Tampa and the Twin Towers merely put the icing on the cake.

Megalogenis serves as a useful bullshit detector on his newspaper colleagues. If, as Kate Legge argues, John Howard is a New Age man, how was it that as late as 2001 a mother could only get the full value of the baby bonus if she stayed at home with the child for five years? And Megalogenis reminds Samantha Maiden that the rhetoric of choice in health and education disguises a ruthless political logic: ‘Howard understood … that there were more votes in helping parents defect to the private systems than in repairing the public systems.’ And if Paul Kelly should get too carried away with the glories of Howard’s governance, Megalogenis reminds him that Howard has so debased the concept of government accountability that the ‘children overboard’ affair, the question of the missing weapons of mass destruction and the Australian Wheat Board scandal became simply ‘exercises in semantics’. Apropos of Greg Sheridan, he provides a detailed refutation to show how unrevolutionary is Howard’s policy towards Indonesia. And he seems much more sceptical than his colleagues about the misbegotten and maladroit war in Iraq. As he rather wickedly notes: ‘We had a foot in each camp: as a member of the coalition of the willing and as Saddam Hussein’s bag man.’

Kelly recently advised a left-leaning audience to put aside their morality in assessing the Howard government. Morality, ‘ay there’s the rub’. Is it right that money should be lavished on private schools while public schools deteriorate? Whatever their justification, should the asylum-seeker policies have been executed in so inhumane a manner? How can we justify going along with the pre-emptive war in Iraq, given that most of the justifications have fallen by the wayside? Should welfare resources be spread so generously up the income ladder, while an underclass develops and festers? These issues of morality are peripheral in both volumes, yet the answers to them will ultimately deter-mine the reputation of the Howard government.

Comments powered by CComment